Darkness covers your approach as you alight on the riverbank. Swiftly, you hide the boat and shoulder your gear. The mission is clear: capture or kill your target; rendezvous at the extraction point; get out. You have two days. Nodding to your team, you set off toward the glowing lights of Vaillant.

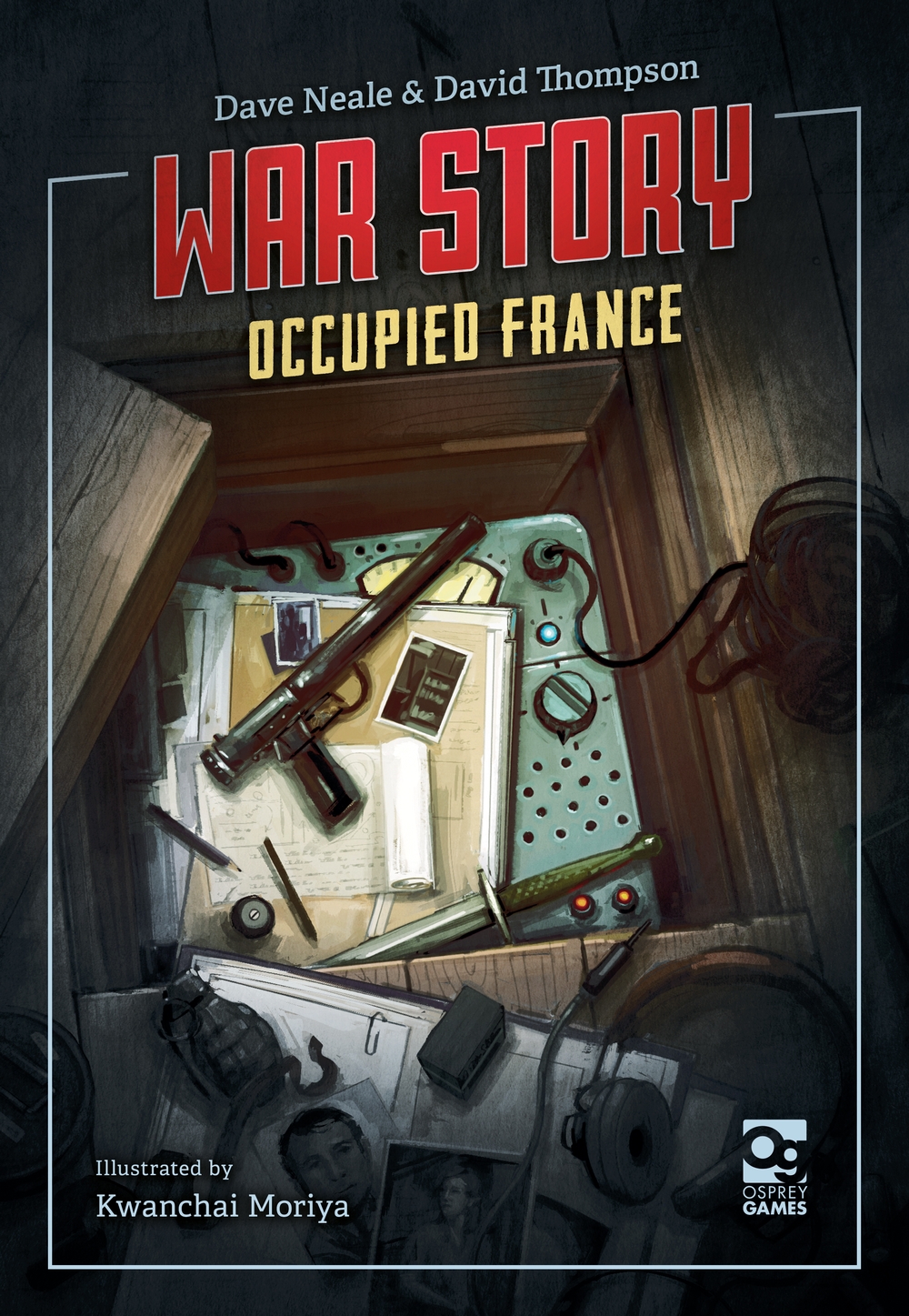

War Story: Occupied France is a co-operative narrative game for one to six players set in World War II occupied France that captures the stakes and tension of espionage and resistance warfare. Your team of covert operatives is all that stands between the infamous German officer Heidenreich and the systematic destruction of French Resistance forces in Morette.

Through three replayable story missions, you must exploit the specialties of your chosen agents to uncover information, enlist allies, and obtain weaponry. Engage occupying forces on tactical encounter maps where careless positioning could cost your agents' lives. Remember, no plan survives contact with the enemy...and time is running out.

This is the story of how War Story: Occupied France came to be…

Origin

The origins for War Story: Occupied France can be traced back to late 2020, almost four years ago. Dave Neale and I had met years earlier as part of a design and playtest group in Cambridge. Over the years we stayed in touch, but it was in November of 2020 when Dave reached out to me and asked me this:

“Hi David. I've been thinking about the tentative narrative war game we floated a while back, and I'm still interested in the idea if you are too. But I was also wondering what are the possible stories we could tell – as in, is there anything more unusual or nuanced than traditional war stories about a battle? I wondered what kind of stories you can think of, perhaps from war films or novels, etc., that haven't been told in wargame format yet? Is there a particular type of story or a particular angle on war stories we could do that hasn't been done?”

Dave and I had chatted earlier about the idea of a narrative-driven war-themed game at Essen Spiel 2019. The idea was to fuze Dave’s expertise with narrative-driven games and my experience with tactical games and knowledge of military history. While there have been wargames that featured emergent narrative in the past, there really hadn’t ever been anything like what we were envisioning.

I eagerly agreed to the idea of collaborating with Dave on the game, and we met for the first time to discuss the concept just a week later, on November 23, 2020. At that meeting we brainstormed various ideas for the game – the setting, overall structure, and how we would track the story. Even as early as this initial meeting, we knew the game would feature some sort of modified “choose your own adventure” approach for driving the narrative, but the details on how that would work, especially for combat, were very much up in the air. We also needed to identify a process and software for tracking the story.

Regardless, coming out of that first meeting in late November 2020, we had a general direction for the game, and we were both very much excited about the possibilities.

Design Approach

The first thing Dave and I needed to do was settle on the specifics for the story’s setting, sketch out the overall story arc, and figure out how we were going to map out the story in a way that would enable a complex, interwoven narrative. I suggested early on that the Special Operations Executive (SOE) would serve as an excellent backdrop for our game. The SOE was a British organization formed in 1940 to conduct espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance in German-occupied Europe and to aid local resistance movements during World War 2. The SOE would provide the players interesting characters with lots of varied options for stories, and it was also a good choice for keeping the scale of the game at the individual character level.

In terms of tracking the complex branching of the story, our first approach was to use draw.io. Draw.io is a software designed for diagramming, and while we were able to use it early on, it really didn’t have the features and capabilities we needed. In the earliest iterations of the game, when we were working through core game design concepts, we would have to track all of the ties between the passages manually, which was tedious and limited the practical complexity for the branching narrative.

During the earliest phases of the design, when we were primarily focused on working through the core mechanisms of the game and sketching out an initial sample storyline, we used a combination of draw.io and manual tracking.

It took us about a month to put together the initial working prototype of the game. In that earliest incarnation, we were working on a story that very much still reflects some of the ideas and plot beats that live on in the War Story: Occupied France final mission, though I’ll refrain from getting into specifics, as I don’t want to spoil the mission.

One thing I do want to mention, though, is that from the very beginning I wanted combat in the game to reflect real-world tactics for small-unit engagements.

An example tactical map from the original prototype

Research and Creating the Setting

Once we settled on using the SOE as the basis of the storyline and background for the characters, Dave and I set about researching the organization, its operatives, and missions. Much of the foundational reading material came from Osprey Publishing, with their excellent books on the topic (for example, “SOE Agent: Churchill’s Secret Warriors”). In addition, I used a wide variety of sources for the small-unit tactics. When possible, I used sources from the time, such as WW2 doctrine manuals and SOE documentation. But in general, small-units tactics really haven’t changed much over the last 80 years.

Another choice Dave and I made early on was to use a fictional setting for the game and characters. We were inspired by the real-world SOE operatives and their missions, but we wanted the game to reflect the history, not try to recreate it as a simulation. Ultimately we decided to set it in a fictional French countryside in the mid-war period, with a focus on the French Maquis and German Gestapo.

Gameplay

For the next 10 months, Dave and I worked on the initial prototype mission for the game – something that would allow us to flesh out the core system and give us something we could pitch to a publisher. Most of the core gameplay concepts came together quickly. Characters would have a range of skills, and the game would ask for checks against those skills – sometimes asking for the highest or lowest skill for a single character, or perhaps asking for the total skill level for all the characters together. It wasn’t until about May of 2021 that we hit on the idea of a pool of tokens that could be shared across the team. The tokens allow players to make critical decisions about when to use their very limited resources to boost checks during the game. At its very core, War Story: Occupied France is a game about making careful, informed choices and managing a very limited pool of resources. The game is purely deterministic – there is no randomness in the game at all. But the variety of choice means that there is no single “best path” and that any combination of agents, choice of paths in the game, and decisions on when to use tokens to boost skills will have a massive effect on the narrative and can lead to very different situations.

Our “bugbear” early on in the design process was how exactly to handle combat. We knew that we generally wanted to handle it through the core narrative-driven process in the game rather than a separate sub-system dedicated to combat. But we went through many, many iterations on exactly how to represent and track combat. In some early versions of the games, weapons had their own effects, we had more ranges of combat, we handled melee combat differently than ranged combat, etc. Ultimately we settled on a system that works entirely within the narrative-driven framework of the game, albeit with the support of tactical maps to provide a visualization of the action. Weapons were streamlined to just two ranges (short and long), and hand-to-hand combat was integrated directly into the game as part of the narrative and tied back to other skills as the situation warranted.

The biggest difference in how we ultimately decided to handle combat and other skill checks in the game is by distinguishing “Firearms” (or a character’s proficiency with guns) and all other “skills.” These two categories defined a characters’ traits, and we created a separate Firearms token in the game that can only be used for boosting combat checks, in the same way skill checks can be boosted with skill tokens.

The last major change to this system was the addition of “Advantage” tokens. These are “wild card” tokens that can be used for either Firearms or Skill checks, but they are fleeting. They are earned during the game to abstractly represent a situational advantage that the characters have, and if they aren’t used quickly, they will be lost.

One other major decision that we made during this early period of design was how exactly the pool of characters would work and how players would interact with them. We considered tying the number of characters to the player count, but this proved problematic primarily in that we wanted the game to tell the story of a small group of agents working together. Ultimately we decided that the players, regardless of player count, would always collaboratively control a pool of four characters at the start of a mission. Of course, casualties in the game are very common, and while there is a larger pool of eight total characters to draw from for the game’s three missions, character death can play a serious role in the game.

Dave and I continued refining our prototype mission for most of the year, typically meeting every other week to work on the game, and we eventually expanded our tests to both guided and unguided playtest groups. Reactions were positive, and by late October 2021, we were ready to pitch it.

Development

On October 25, 2021, Dave and I met with Osprey Games to pitch them the game (which, at the time, we simply called War Stories). Osprey seemed a perfect fit to us: I already had a close relationship with them, having partnered on the Undaunted series, and the idea of a narrative-driven, war-themed game seemed perfect for their catalog. We met with developers Filip Hartelius and Anthony Howgego online, walking them through the demo of our game. The meeting seemed to go well, with Filip and Anthony wanting to take the demo and play it for themselves. Later that same day Filip and Anthony reached out to me and Dave to let us know they had played the game and wanted to sign it. Dave and I were ecstatic!

In his email to us, Filip said:

“Hello David and Dave. We’ve now had a chance to play War Stories twice (as well as had a look through some of the other paths) and I can confidently say that I would love to have Osprey Games publish the game. It’s evocative and effective, and does something truly innovative within the genre.”

Initially Filip and Anthony wanted the game to include five(!) missions, but Dave and I knew immediately that was too much. Each mission in War Story contains a massive amount of content. Players would have to replay each mission many, many times before they could experience every possible path. The word count for War Story: Occupied France ended up exceeding the word count of the average novel. Five missions would have just been too much, and we preferred to focus on quality over quantity. So instead we settled on three missions for the game, which could technically be played in a stand-alone fashion but are really meant to be played as a continuous experience.

Of course, now is when the real work needed to start. Dave and I needed to create a complete storyline, with three missions, while continuing to refine the core game design elements. We soon came together to sketch out the game’s three mission arc. We identified some key story beats, the overall focus of each mission, and some key characters. Our typical approach was for the two of us to come together, discuss the high-level story concepts, and then I would go off to add a bit more detail to the story structure and work on the combat encounters. I would turn over the skeleton of the story structure to Dave, who was also working through some of the non-combat narrative, and Dave would turn my notes into beautiful prose.

We knew that our process for constructing the narrative – the combination of draw.io and manually tracking the branches – was not sustainable. We looked for alternatives and eventually settled on Twine. Twine is “an open-source tool for telling interactive, nonlinear stories” – exactly what we needed. Although it took us a while to find our feet with Twine, primarily in developing a consistent style guide and effective method of file sharing, it really unlocked the potential of the game for us. Previously we had been constrained in the complexity of the branching we were able to use in the game, but no longer. We could track various states and paths throughout the scenario, with numerous interconnected variables and Twine allowed us to ensure we weren’t breaking our story.

To give an example of the complexity, Dave and I created a special demo mission for War Story: Occupied France to be used at conventions such as GenCon and Spiel. There is a combat encounter late in the mission that consists of 125 interconnected passages, though players will only ever encounter a small number of those passages in a single play of the game.

Here is a visualization of just part of that single combat encounter.

We continued refining the game until mid-2023, when we turned it over to Osprey Games for their heavy lift on the game. Between late-2021 and mid-2023, the developers at Osprey had changed, with Filip and Anthony leaving, and new developers Rhys ap Gwyn, Jordan Wheeler, and Luke Evison joining the team. They took our three missions and began the Herculean task of formatting them, looking for opportunities for improvements, leading the art direction, and just generally taking what I think was a good game and making it something incredible.

I’ve partnered closely with Osprey Games for almost ten years now, and I can honestly say that no game required more work, care, and attention to detail than War Story: Occupied France (with the possible exception of Undaunted: Stalingrad, which was a similarly massive undertaking). The amount of effort and love put into the game by the Osprey team was remarkable.

Art and Graphic Design

I was blown away when my friends at Osprey Games told me that Kwanchai Moriya was going to be the artist for the game. Kwanchai has always been one of my favorite artists. The first game of his that really grabbed me away was Days of Ire: Budapest 1956. Ever since then, I’ve closely followed his work and dreamed of collaborating. So when I learned he was going to work on War Story: Occupied France, I couldn’t have been happier.

Kwanchai’s art really helped the game come to life. Every illustration captures the story Dave and I were trying to tell beautifully. And of course, the range of his work is really on display in the game, from illustrations of the operatives, to the tactical encounter maps. I couldn’t be happier with the art for the game, and I think players are going to feel the same way.

The graphic design was another critical area for the game. Graphic designers Jared Viljoen and Dídac Gurguí did an amazing job working closely with the Osprey development team to integrate subtle but effective elements throughout the rules, the mission books, and the other components to help players easily play the game without all the extra cognitive load that could have come if the game relied more heavily on text to convey critical information.

Release

When War Story: Occupied France is released on October 8, 2024 – after demos taking place at Essen Spiel on October 3rd-6th – it will mark the end of a four-year process to make the game a reality. From that first message Dave sent me, inviting me to collaborate with him, to the published version of the game, the creative process for War Story: Occupied France has been extremely exciting for us. We hope that everyone enjoys playing the game as much as we enjoyed creating it!

*******************

War Story: Occupied France is out everywhere now.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment