The massive extent of underground warfare during 1914–18 has never been surpassed, but a resurgence in recent decades means that its relevance is still felt today. It was excellent to be asked by Osprey to write this title for their Elite series. Not only is the subject a logical follow-up to my World War I Gas Warfare Tactics and Equipment title, it is also one with which I have been fascinated for upwards of 35 years. My interest dates from my early twenties when I was Assistant Curator at the Royal Engineers Museum and took part in the exploration of a World War I tunnel system deep beneath Vimy Ridge in France. Parts of this had not been visited since the end of the war and I was left completely hooked on tunnel warfare. I began to gather any information that I could on the subject and have since been lucky enough to visit many other surviving 1914–18 underground sites.

The ultimate aim of the first tunnelling operations during this period was to detonate mine charges beneath the opposing trenches, but this was extremely difficult to achieve. Instead, a battle beneath no man’s land escalated that mirrored, and even exceeded, the trench warfare above. If commanders were to defend their lines, they had no choice but to mine. Thousands of men were soon toiling underground in a struggle of nerves, skill, and the sheer muscle of miners. Explosive mines and camouflets destroyed the opposing tunnels or flooded them with deadly carbon monoxide, and deeply scarred the surface of no man’s land with huge craters. The threat of sudden death from below added yet another element of fear and danger to the infantry in the trenches. For those driving the tunnels, break-ins led to terrifying underground combat in the darkness, while fearful hours of listening were spent trying to deduce an opponents’ location and activity from sounds and vibrations.

This book has been the opportunity to pull together many years’ of research, and new discoveries since the publication of my last book on the subject in 2010, including new French and German sources and many unseen photographs. The format of the Elite series enables a great deal of information to be packed into each publication. It is also a valuable exercise in writing a text which is focused and concise. I wanted to explain the place that underground warfare had in the dynamically changing fighting methods of 1914–18, and how it was understood in the German, French and British armies.

Military mining was already an ancient technique which originated in tunnelling beneath the walls of an opponent’s castle to create a breach. It had fallen into disuse, as artillery rendered fortresses obsolete, only to be revived in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 when it was used against otherwise impregnable field entrenchments. This was a precursor of the trench warfare stalemate of 1914, when mining spread quickly along the newly-formed trenches of the Western Front, breaking out wherever they were closer than a few hundred metres. During 1915, mines were used for their shock and destructive power to support infantry attacks, but the French and German armies were to abandon their use in favour of developing infantry–artillery tactics. The British continued using massive mines in launching attacks, in particular at the Somme in July 1916 and Messines the following year. The reasons for this were, initially, as a means of compensating for lack of artillery but in particular the very effective British Tunnelling Companies caused mines to persist in British operational planning. By the time the nineteen massive mines were fired beneath the Messines Ridge in June 1917, advances in the combined-arms battle had rendered military mining obsolete.

Underground warfare extended beyond mining to encompass extensive underground accommodation to protect against the ever-present shellfire, with dugouts and tunnels enabling thousands of troops to be massed for attack and defence. The German use of underground shelters for trench garrisons was highly effective at the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. Allied tactics developed in 1916–17, however, effectively turned them into death traps. The aftermath of the Cornillet tunnel tragedy of May 1917, captured in a chilling photograph, saw the death by suffocation of more than 300 trapped German soldiers.

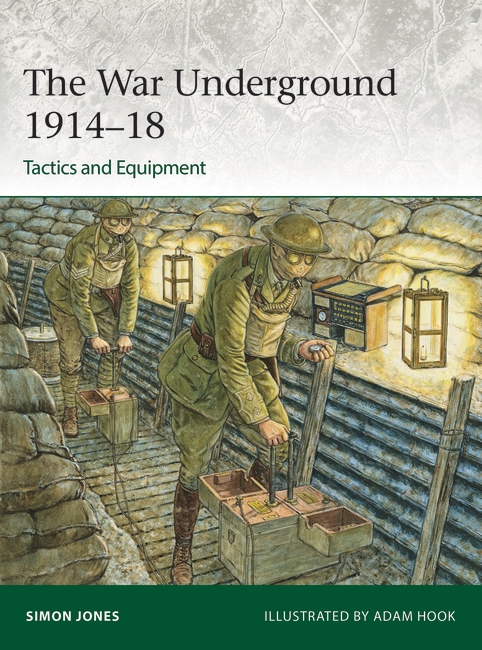

The photographs and artwork convey the nature and reality of underground warfare. The inclusion of more than fifty images was a chance to publish many of the rare photographs that I’ve discovered over the years, and to use some of my own photographs taken during underground explorations. Newly available digitized archives have enabled German, French, Italian and New Zealand images to be seen in print, many for the first time. One remarkable photograph shows German Pioneers connecting the firing circuits in an explosive-filled mine chamber, doing so alarmingly by the light of a naked candle (and presumably photographed by magnesium flash). I sourced the image in an outstanding private collection in Australia but was later able to identify the date, location and unit when I also found it in an album in the Bavarian State Archives. The rarest photographs show armed men underground, such as one of a French sapper with a carbine used for firing tear-gas rounds, evidence of the deployment of chemical weapons in this environment.

The colour artwork was a unique opportunity to bring to life the techniques of underground warfare. It also presents a challenge to the author in briefing the artist, and the expert knowledge of Osprey readers made me determined that they would be as accurate as possible. It was remarkable to see my detailed briefs turned into powerful illustrations by Adam Hook. It’s difficult to pick a favourite from these, but one that’s definitely up there is the French geophone listener, who crouches alone in a tunnel attempting to detect sounds of German activity. The device gave the French and British a much-needed advantage against German miners, who had led in the use of electrical microphones for detecting enemy mining activity. I am also fascinated by the breathing apparatus that was vital for survival in tunnels flooded by deadly carbon monoxide gas following the detonation of mines and camouflets. These complex devices have been skilfully depicted and I hope that it inspires model makers to explore the topic. No photograph survives of the ‘clay-kicking’ technique used by British and Commonwealth tunnellers in Flanders. For the artwork, I chose the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company working beneath Hill 60, together with a variety of different ‘grafting tools’ used by the independently-minded tunnellers. The sheer scale of underground networks is conveyed in a reconstruction of a complete Western Front tunnel system, created at La Boisselle on the Somme by German, French and British miners in 1915–16 and comprising some 5km of tunnels. Finally, the incredible and gruelling mountain warfare on the Italian front is represented by Alpini miners using compressed-air jackhammers to drive through the rock of the Castelletto mine.

Find out more in The War Underground 1914–18: Tactics and Equipment

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment