In 1910, Korea ceased to be an independent country and became a colony of the Empire of Japan. Nationalistic Koreans who were unwilling to see their country perish went en masse into exile to organize armed resistance movements, either to Russia (later the Soviet Union) or to China. Those who stayed in Korea became citizens of the Japanese Empire, and many joined the Japanese military and served in World War II, often adopting Japanese names. In 1945, the surrender of the Japanese Empire meant that Korea could once again regain its independence after 35 years of resistance.

By the terms of the Yalta Agreement, the Soviet Union and the United States occupied the northern and southern parts of the Korean Peninsula, thus splitting Korea in two. The two regimes espoused fiercely opposing ideologies, with the North backed by the Soviet Union and the South by the United States. In the North, the Korean People’s Army (KPA), formed from a nucleus of police and security forces, was established on February 8, 1948, pre-dating the establishment of the country Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) by seven months. This embryonic army was subsequently strengthened by a large-scale transfer of Koreans serving in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1949.

After the surrender of Japan, the Korean peninsula was in a political vacuum. Nationalistic Koreans overseas rushed back and quickly formed a provisional government and organized paramilitary forces in the northern part of the Soviet-occupied Korean peninsula. With Soviet backing, the northern part of Korea naturally attracted the left-wing elements of those exiled Koreans, those exiled in the Soviet Union and those in China, especially those living in areas controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. Both groups of exiles had one thing in common, in that they were experienced war veterans; some participated in the war against Nazi Germany and its allies, serving in the Red Army, while others fought in Mao’s army against the Japanese and later also against the Chinese Nationalists in the Chinese Civil War. Kim Il-sung, the grandfather of today’s leader of the DPRK, was one of those nationalistic Koreans who served in the Red Army and was keen to see the rebirth of an independent Korea.

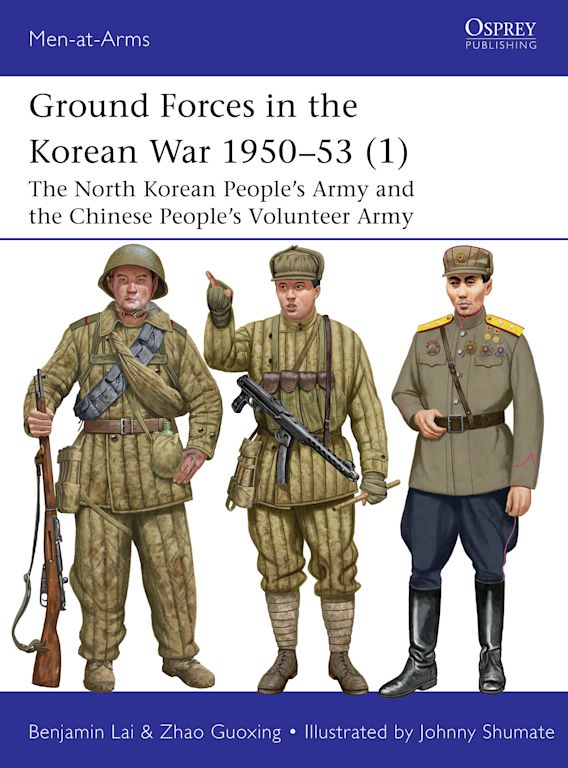

There is a common misconception that the KPA was entirely a puppet of the Soviet Union, formed by the Soviet Army, but this is untrue. The KPA may have been equipped with hand-me-down Soviet weapons and dressed in Soviet surplus, but the North Koreans were highly independent and always strove to establish themselves as Koreans rather than Soviet Koreans or Chinese Koreans.

The story of the KPA cannot be told without mentioning Kim Il-sung, the founder of the DPRK and the KPA. Born in China to exiled Koreans, he formed and led a guerrilla army in north-eastern China in 1932 with other exiled Koreans to fight the Japanese. Pressure from the Japanese anti-guerrilla forces subsequently prompted him to retreat with his forces into the Soviet Union, receiving instruction in intelligence gathering as the Red Army’s 88th Independent Brigade. By 1945, Kim was a captain in the Red Army, and his daring nature soon attracted Soviet attention.

The bulk of the KPA was formed from exiled Koreans in China, veterans of the PLA. At the end of 1949, Mao saw the need to demobilize his vast army, and just at the right time, Kim Il-sung called for Koreans in China to return to their motherland. These Koreans joined the KPA in large numbers, often still in the same Chinese units in which they once served. Exiled Koreans also came from the Soviet Union, determined to rebuild their mother country; these exiles were much less numerous and mainly served in leadership roles. Technical arms such as the Armor Corps and the Air Force became the favorite of Soviet Koreans. Returning to Korea was also a group of civilians, often intellectuals and technocrats, who became the backbone of the newly born DPRK.

By the outbreak of the war in June 1950, the KPA had rapidly expanded from a security force armed with small arms only to a modern army with tanks, heavy artillery, and aircraft, including infantry divisions, a tank brigade, and an aviation division, as well as a well-developed command structure, with personnel who possessed a wealth of combat experience. Thus, in the opening stages of the Korean War, the KPA distinguished itself in operations against the South Korean forces, which was intended and equipped to fight pro-North guerrilla operating in the South.

Owing to the UNC forces’ superior numbers of troops and advanced weaponry, the KPA suffered heavy losses in the ensuing battles, exposing its fatal shortcomings. After a series of reverses in 1950, the KPA became a shadow of its former self, with most of the recruits being poorly trained students and peasants with no combat experience. They saw limited direct combat, serving under the Chinese and operating under their orders until 1953.

The KPA is a subject seldom explored in English-language publications; to understand more, buy a copy of Ground Forces of the Korean War 1950–53: The North Korean People's Army and Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, in Osprey Publishing’s Men-at-Arms series.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment