Often overlooked by aviation historians and writers – myself included! – is the aspect of training. This is possibly because it is not considered a particularly glamorous aspect of the ‘combat’ narrative. It was, however, essential.

By late 1944, the Nazis’ labour commitment to the production of Me 262s was significant. On 31 December 1944, 28,766 ‘operatives’, exclusive of personnel engaged on main jig construction and research, were employed in production, comprising 10,553 hands at Messerschmitt Augsburg and 7,710 at Regensburg. No fewer than 10,503 personnel were employed by main contractors and sub-contractors. Of the overall total, 48 per cent were categorised as ‘productive’ as opposed to ‘unproductive’, the former comprising hands working on component manufacture and sub- and main assembly, whilst the latter covered senior administrative personnel and their staffs, senior engineers and test hands, and personnel involved with raw materials.

According to a report prepared by Dipl.-Ing. Ludwig Bölkow, a senior aerodynamicist and engineer based at Messerschmitt Oberammergau for a senior SS personnel officer in the Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment, a total of 265 aircraft had been produced by October 1944, of which 30 had been destroyed in Allied air attacks. This figure was below the planned output and, with little prospect of any major improvement in conditions by the end of the year, it was forecast that production would total 130 in November and 200 in December.

Bölkow concluded that it would be impossible to improve things much beyond this, and that considerable effort would be required to reach even a ‘respectable’ level by December. The principal challenges were the shortages of jigs and tools, a persistent lack of skilled labour and what he saw as ‘the bureaucracy of the RLM and the Todt Organisation’. This had an adverse effect on flight testing and acceptance because a large numbers of components still had to be made by hand, a situation compounded by transport problems. Junkers’ serious shortage of the fitter personnel required for the reception and servicing of Jumo engines also presented Messerschmitt with a serious problem.

This view is lent credence by the opinions of Gerd Lindner, a Messerschmitt director and technician, and former chief research test pilot at Lechfeld. According to a post-war Allied interrogation report, Lindner believed satisfactory levels of production ‘were capable of attainment given a due degree of priority and general support for Messerschmitt from the various competent authorities, and he further opined that, with the firm having created a unified production control, it was for the Rüstungsstab [a government and SS task group] to follow suit and nominate a single authority with overriding powers to take the place of the numerous special and factory commissioners who had so far encumbered the scene’.

However, according to a summary based on Delivery Plan 227/1 of 15 December 1944, which was prepared by Messerschmitt’s Sonderausschuss (Special Committee) F.2, total deliveries of all types from the Augsburg plant up to 30 November was 411, whereas Regensburg delivered 26, with all aircraft from the latter being A-2a ‘bombers’. The bulk – 124 aircraft – were A-1a interceptors, whilst seven A-2as had been modified as ‘auxiliary reconnaissance’ aircraft fitted with an SSK camera and two MK 108 cannon. By the end of the year, total output for all variants was planned to reach 637 aircraft.

Despite production difficulties and bottlenecks, rates of production and the number of operational Me 262 units slowly grew in late 1944, and so an efficient and structured training system became essential.

In November 1944, III./EJG (Ergänzungs-Jagdgeschwader) 2 had been formed from what remained of Erprobungskommando 262 at Lechfeld. The intention was to set up a dedicated Me 262 operational training unit that would be able to offer fighter pilots converting to the jet a comprehensive and thorough training programme. About 50 pilots were initially assembled from both fighter and bomber units, as well as fighter school staffs, and a selection was made of promising new pilots who were about halfway through their operational fighter training pool syllabus. These were given a pre-jet flying course requiring them to finish their regular 20 hours’ flying time in conventional fighter aircraft with the throttles fixed in one position, reproducing a technical problem found when flying the Me 262, the throttles of which were not to be adjusted at high altitudes.

Upon their arrival at Lechfeld, all pilots – both experienced and inexperienced – were given three days’ theoretical instruction in the operation and functioning of jet engines and the features and flying qualities of the Me 262, as well as some practice in operating the controls in a wingless training model. This introduction was followed by a course at Landsberg in the operation of conventional twin-engined aircraft. Pupils were given five hours’ flying time in the Bf 110 and Si 204, practising take-offs, landings, flight with the Zielvorsatzgerät 16 (radio course indicator), instrument flying and flying on one engine. Upon completion of the course, the pilots returned to III./EJG 2 at Lechfeld, where they were given one more day of theoretical instruction before beginning conversion to the Me 262.

Practical instruction on the Me 262 began with half a day’s exercise in starting and stopping the jet motors and taxiing. If a two-seat Me 262B-1 was available, students had the opportunity to practise stalls with an instructor, as well as landing on only one jet and operating the landing gear with compressed air. Instrument flying in a Siebel 204 was also interspersed with the jet training.

This was considered to be the absolute minimum with which a pilot could qualify for operational readiness on the Me 262. However, such training was severely restricted due to the shortage of the Me 262B-1 and, even by the end of January 1945, III./EJG 2 recorded only three such machines on strength. What the Luftwaffe did achieve with its meagre force of Me 262s was remarkable, however, and my new book on the Me 262 units attempts to demonstrate that.

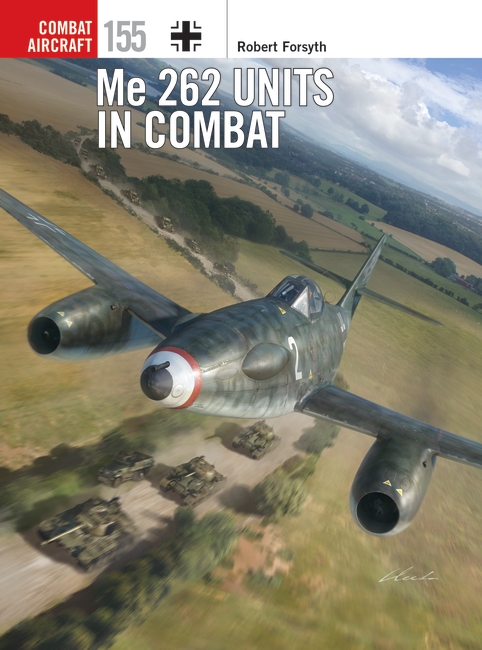

Read more in Me 262 Units in Combat

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment