On the eve of the beginning of the Civil War in April 1861 the total paper strength of the United States Regular Army was 16,402 officers and men, of whom 14,657 were present for duty scattered over a large continent (Eicher & Eicher 2001: 46). Within this number there were four general officers – Winfield Scott as major general, and William S. Harney, David E. Twiggs, and John E. Wool as brigadier generals – plus about 1,104 commissioned officers.

Of these, 361 staff officers were assigned to six departments, two corps, and one bureau, each headed by a colonel. These consisted of the Quartermaster Department, Ordnance Department, Inspector- General’s Department, Medical Department, Pay Department, and Subsistence Department; the Corps of Engineers; the Corps of Topographical Engineers; and the Bureau of Military Justice. To these were added the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau in May 1863, and the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in March 1865.

Of 743 line officers, 351 served in ten infantry regiments; 210 in four artillery regiments; and 182 in four mounted regiments (Newell 2014: 50). Approximately 13,500 noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and enlisted men were assigned to various branches of foot and mounted service. About 62,000 officers and men served in the Regular Army during the Civil War years (1861–65). By March 31, 1865, however, it consisted of just 21,669 officers and men, of whom only 13,880 were present for duty (Eicher & Eicher 2001: 46).

Of the new branches of service, specialists, and Territories, the United States Colored Troops enrolled 99,337 men, while the United States Indian Home Guard recruited 3,530 men (Eicher & Eicher 2001: 53). A total of about 2,570 men enlisted in the two regiments of United States Sharpshooters (Stevens 1892: 512). The Invalid Corps/Veteran Reserve Corps contained about 60,000 men from 1863 through 1865 (Wagner et al. 2002: 441–42). Although the overall size of the Ambulance Corps is not known, by the summer of 1864 that in the Army of the Potomac alone numbered 66 officers and 2,600 men (Ginn 1997: 11–13). The Military Telegraph Service amounted to 1,079 officers and men (Bates 1907: 20). About 2,900 officers and men served in the Signal Corps, albeit not at any one time (Coker & Stokes 1994: 3).

In the Territories a total of 16,871 volunteers were provided to the Union Army as follows: Colorado 4,903; Dakota 206; New Mexico and Arizona 6,561; Nebraska 3,157; Nevada 1,080; and Washington 964 (Eicher & Eicher 2001: 53).

General Officers

Since 1787 the President of the United States had been the Constitutional Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, and of the state militia when called into service. On March 4, 1861, this became the responsibility of President Abraham Lincoln. The ranking officer of the US Army was known as the General-in-Chief with the rank of either major general or lieutenant general. Throughout the Civil War years this role was fulfilled by Winfield Scott (July 5, 1841–November 1, 1861); George B. McClellan (November 1, 1861–March 11, 1862); Henry W. Halleck (July 23, 1862–March 9, 1864); and Ulysses S. Grant (March 9, 1864– March 4, 1869). Abolished during the Revolutionary War (1775–83), the rank of lieutenant general was revived in 1855 when Scott received a brevet promotion to that rank. Both Halleck and McClellan were major generals. In 1864, Grant was appointed lieutenant general when he took command of the Union Army.

With headquarters at Washington, DC, the Quartermaster General in charge of supplies, including clothing and equipage, for the Army until April 22, 1861, was Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston. Following the outbreak of war, Johnston resigned to enter the Confederate service, and was replaced by Brigadier General Montgomery C. Meigs of the Corps of Engineers, who did not take up the post until June 13, 1861. As a result, Major Ebenezer S. Sibley served as acting chief of the department. Once in place, Meigs proved to be a competent administrator in times of emergency, and remained in post almost continually until 1882.

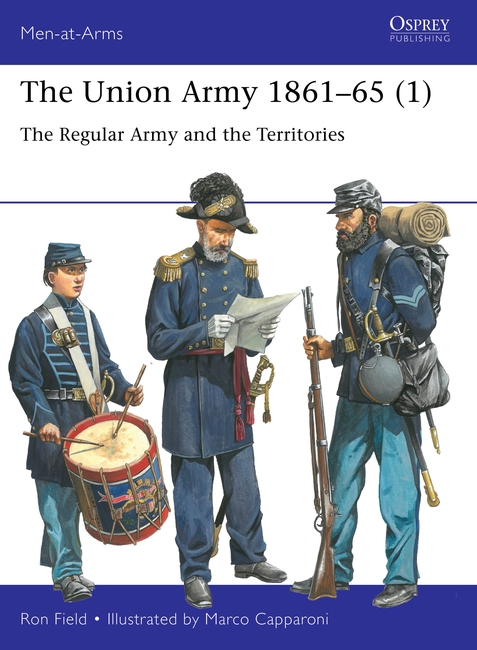

Since 1858, the dress uniform for generals consisted of a dark-blue Pattern 1851 double-breasted frock coat with a skirt that extended “from two-thirds to three-fourths of the distance from the top of the hip to the bend of the knee”; plain dark-blue trousers; and a Pattern 1858 hat of best black felt (Regulations 1861: 3 & 6). Of “General Staff” pattern and bearing a partial representation of the coat of arms of the United States, the gilt, convex buttons on the coat were arranged in three sets of three for a major general, and four sets of two for a brigadier general. When Grant became a lieutenant general in 1864, the button arrangement remained the same as for a major general. The coat collar and straight cuffs were of dark-blue velvet. On duty, a general officer wore gold bullion epaulets with “dead and bright” gold bullion fringe, ½in. in diameter and 3½in. long. The epaulet straps for a General-in-Chief bore three silver embroidered five-pointed stars in graduated sizes with the largest inside the brass crescent; for major general, two silver embroidered stars with the largest star in the crescent; and for brigadier general, a single star.

Epaulets were replaced by gold-bordered shoulder straps with a black velvet ground bearing the same configuration of embroidered stars when not on duty, and on certain duties off parade, such as Courts of Inquiry and Boards, inspection of barracks and hospitals, work parties and fatigue duties, and upon the march, except when there was an immediate expectation of meeting the enemy, and also when the “cloak coat” was worn. On November 22, 1864, War Department General Orders No. 286 permitted officers to dispense with all rank insignia except for shoulder straps.

You can read more in The Union Army 1861–65 (1)

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment