The 1st Marine Division’s so-called “end of war” campaign began October 26, 1950, when Marines landed at Wonsan in northeast Korea.

But the division’s 78-mile march into the bitter-cold Taebaek Mountains did not end the Korean War at the Yalu River with the defeat of the North Korean army. Instead, it introduced a powerful new enemy: Red China.

Although General Douglas MacArthur’s command denied it, 400,000 Chinese soldiers had secretly crossed the Yalu River from Manchuria into North Korea, to strike the two United Nations armies there.

At Yudam-ni, west of the Chosin Reservoir, 90 miles south of the Yalu, temperatures had fallen well below zero on November 27. The 1st Division’s Fifth and Seventh regiments were dug in and expecting trouble.

It came with a dissonant blast of bugles, whistles, and cymbals, announcing that the battle for survival had begun.

***

The fall 1950 campaign in North Korea was supposed to be a triumphal march to the Yalu River, ending the war that began with North Korea’s invasion of the south in June.

The allies had defeated the North Korean army at Pusan and Inchon and driven it from Seoul, South Korea’s capital. It was in disordered retreat, and many thought hostilities would end by Christmas.

The 1st Marine Division’s transit from Inchon, on Korea’s west coast, to Wonsan, on the peninsula’s northeast side, was supposed to take two days, but Wonsan Harbor was strewn with 2,000 mines. Day after day, the 72-ship convoy sailed up and down the Korean coast while minesweepers cleared the harbor.

Finally, on October 26, the division landed unopposed at Wonsan.

It was an inauspicious start to a desperate battle for survival in the North Korean mountains in below-zero weather against a new foe – Mao tse-Tung’s Red Army.

Mao had repeatedly warned that if U.S. troops crossed the 38th Parallel into North Korea, Red China would intervene to protect its Yalu River border.

The warnings were ignored. X Corps, whose 90,000 men included the 1st Marine Division and the U.S. Army’s 7th Division, marched into northeast Korea, while the 120,000-man Eighth Army under General Walton Walker pushed into the northwest.

On November 2, at the village of Sudong, two regiments of the Chinese 124th Division suddenly attacked the Seventh Marines.

With overwhelming firepower and close-air support by Corsair fighter-bombers, the Marines cleared the area around Sudong. On November 3, the Chinese abruptly broke off contact and vanished.

At about the same time at Unsan in northwest Korea, Chinese troops mauled two U.S. division of the Eighth Army before also disappearing.

“In order to hook a big fish, you must let the fish taste your bait,” People’s Liberation Army commander Peng Dehuai counseled his top officers.

That meant luring the enemy armies into a trap.

Although prisoners admitted being Chinese regulars and enumerated the Chinese units in the area, MacArthur and his staff insisted they were volunteers retreating to the Yalu.

General Ned Almond, MacArthur’s chief of staff and X Corp’s commander, ordered the Marines to resume their march to the Yalu.

General O.P. Smith, the 1st Division commander, wrote to Marine Commandant Clifton Cates, “I do not like the prospect of stringing out a Marine division along a single mountain road for 120 air miles from Hamhung to the [Manchurian] border. I believe a winter campaign in the mountains of Korea is too much to ask of the American soldier or Marine.”

Receiving no support from Cates or other superior officers, Smith surreptitiously slowed the march north.

“We pulled every trick in the book to slow down our advance, hoping the enemy would show his hand before we got even more widely dispersed than we already were,” said Colonel Alpha Bowser, Smith’s operations officer. “At the same time, we were building up our levels of supply at selected dumps along the road.”

The depots included the hub at Hagaru-ri on the southern end of the 30-mile-long Chosin Reservoir; at Koto-ri, 11 miles to the southeast; and at Yudam-ni, 14 miles northwest of Hagaru-ri.

On November 26 and 27, the Chinese trap snapped shut.

Mao ordered General Song Shihun’s 150,000-man 9th Army Group to annihilate the 1st Marine Division.

During the moonless, bitter-cold night of November 27 at Yudam-ni, amid blaring bugles and shepherd’s horns, three Chinese divisions attacked the 9,000 Marines defending the hamlet, shouting, “Nobody lives forever! You die!”

“They came in a rush, like a pack of mad dogs,” said Corporal Arthur Koch.

“It was like Custer’s Last Stand,” said Lieutenant John Yancey, whose Easy Company was driven from a hill crest east of Yudam-ni.

From behind Chinese bodies stacked like sandbags, the Marines fired until their rifle and machine-gun barrels glowed. The lines held.

Ordered to withdraw to Hagaru-ri, the two Marine regiments had to first break through enemy roadblocks on the single-lane road, and reach a company of Seventh Marines atop the strategically vital Toktong Pass.

Isolated for five days, Fox Company had repelled repeated attacks. During the night of December 2–3, a composite Seventh Marines battalion made a grueling overland march from Yudam-ni and relieved Fox Company. Of its 246 men, just 82 were still able to fight.

Fox Company and its rescuers wiped out a Chinese daytime attack and opened the mountain pass to the Yudam-ni column.

Singing “The Marines Hymn,” the Fifth and Seventh Marines marched into Hagaru-ri with hundreds of casualties and most of their dead.

The 3,000 Hagaru-ri defenders cheered “the magnificent bastards” and breathed a sigh of relief. The hamlet had withstood nights of enemy assaults, but it had been a close thing.

Smith’s need for reinforcements had days earlier led a relief force of 925 men to set out from Koto-ri for Hagaru-ri with 29 tanks. Chinese troops mauled the column in “Hellfire Valley,” yet 17 tanks and 400 men got through to Hagaru-ri.

Transport planes were evacuating the 500 wounded already at Hagaru-ri, using an airfield scraped from the frozen ground by Marine engineers. The Yudam-ni column brought 600 more wounded.

East of Chosin Reservoir, the Army’s 3,000-man 31st Regimental Combat Team had kept two Chinese divisions at bay for five days before collapsing. Unable to reach Hagaru-ri or be reinforced, it became the only regiment destroyed during the Korean War.

On December 6, the Marines from Hagaru-ri and Yudam-ni, and a few hundred 31st RCT survivors left Hagaru-ri, bound for Koto-ri, the Sea of Japan, and evacuation. All surplus gear and rations were destroyed.

Before the 14,000 men and tanks and artillery could leave, East Hill, overlooking the road out of Hagaru-ri, had to be retaken from the remnants of the Chinese 27th Army. The depleted Fifth Marines used ropes to scale the steep, icy hill on December 5, attacking early the next morning.

Tens of thousands of reinforcements from the Chinese 26th Army reached East Hill that day after a 100-mile

forced march through the mountains. The exhausted, half-starved troops were flung into the battle, which lasted 22 hours before the Marines secured the hill.

Marine and Navy fighter-bombers formed an umbrella over the column marching to the sea, their close-air support missions destroying Chinese formations in the hills alongside the road.

About 800 enemy troops assaulted the column at a place where two artillery batteries were in transit. The artillerymen unlimbered nine howitzers, thrust the muzzles between the trucks and blasted the enemy, firing 600 rounds during the hour-and-a-half battle. More than 700 enemy soldiers were killed or wounded.

Southeast of Koto-ri, the enemy had blown the Funchilin Pass bridge, which spanned huge pipes bringing water from Chosin Reservoir to hydroelectric plants in the valley 2,000 feet below. The 29-foot fissure might be bypassed on foot paths, but unless the bridge was replaced, tanks and trucks would have to be left behind.

A risky plan was conceived for parachuting 22-foot-long, 2,500-pound Treadway bridge sections to Koto-ri and installing them at the bridge site.

Amazingly, the plan worked. Brockway trucks trundled six sections to the blown bridge. A new bridge was laid over a lattice-work of timbers, with frozen Chinese bodies filling the holes.

The column crossed over and descended to the coastal plain, where trains and trucks transported many men to Hungnam to board naval ships.

The last of the 105,000 troops evacuated from North Korea departed on December 24 – not for home, but for battlefields in South Korea – along with more than 98,000 North Korean civilians.

Mao had successfully driven United Nations forces from North Korea, but at a high cost: the 9th Army Group reported 48,356 soldiers lost during the Chosin Reservoir campaign – 19,202 combat casualties and 28,954 frostbite victims.

The 1st Marine Division withstood attacks by seven Chinese divisions to fight another day, with 604 men killed in action; 4,418 combat casualties; and another 7,313 non-battle casualties, largely frostbite or shock victims.

The campaign marked the start of a much larger war across Korea’s midsection, ending in a truce two and a half years later.

***

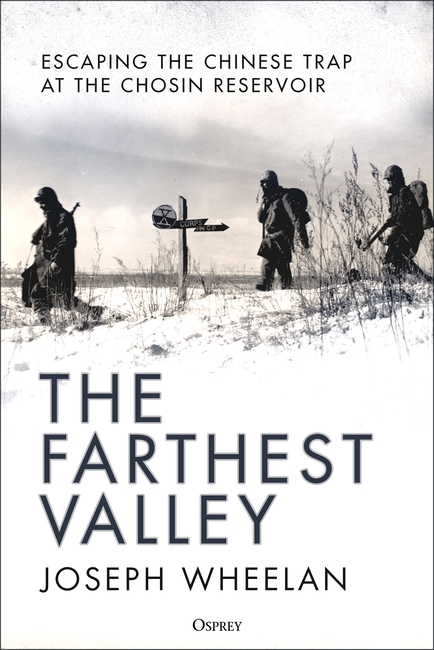

Joseph Wheelan’s newest book is The Farthest Valley: Escaping the Chinese Trap at the Chosin Reservoir. He is also the author of 11 other books on American history, including three about the Pacific War: Bitter Peleliu: The Forgotten Struggle on the Pacific War’s Worst Battlefield; Midnight in the Pacific: Guadalcanal – The World War II Battle That Turned the Tide of War; and Bloody Okinawa: The Last Great Battle of World War II.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment