On 25 June 1950, North Korea launched an all-out attack on its southern neighbour, the Republic of Korea (ROK). Despite the Communists’ early success in driving the poorly equipped ROK Army and its US allies to the brink of disaster, the amphibious landing of US forces at Inchon on the western coast of the Korean peninsula forced the North’s Korean People’s Army (KPA) to retreat all the way to the Sino-Korean border. Aside from one or two famous battles, such as Imjin River, Bloody Ridge and Heartbreak Ridge, this is what most military enthusiasts remember about the Korean War. The dialogue and discourse are largely one-sided, delving primarily into Western achievements and memories of veterans from the West. Almost nothing is known about the forces opposing the United Nations Command (UNC): the KPA and its ally, the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA). Drawing upon unfamiliar Chinese and Korean sources and original wartime reports, Ground Forces in the Korean War 1950–53 (1): The North Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army aims to redress the balance.

The Chinese volunteers came to Korea in late 1950 surreptitiously, to the surprise of the UNC forces. The PVA’s early success routed several ROK divisions and shocked the Americans. Despite suffering horrendous casualties, the Chinese severely mauled the UNC troops in the battle of Lake Changjing (Chosin Reservoir). They forced the withdrawal of the 1st Marine Division, the ROK I Corps and the US X Corps from the eastern flank of the Korean peninsula, in a battle that entered into the lexicon of Chinese military history.

Although victorious in the recently concluded Chinese Civil War, the Chinese People’s Army (PLA) was still essentially a light-infantry force, short of heavy and support weapons and without a navy or air force. Facing the Chinese volunteers was a UNC army led by battle-hardened World War II veterans and armed with the latest weaponry. Therefore, when Mao decided to enter the Korean conflict, the Chinese politburo did not support it at first. Why China went to war in Korea and how Mao made the decision is not well understood by many in the West.

While many Chinese families lost sons and husbands in this ‘forgotten’ war, many in the West do not realize that Mao also lost his favourite son, Mao Hanying (Sergey Zedonovich Mao), in Korea, his death being attributed to a US air attack on the headquarters of Peng Dehuai, the overall commander of the Chinese forces in Korea. It is said that when Mao was eventually told of his son’s death, he was devastated and did not eat for many days. Mao Hanying is buried in North Korea, according to the wishes of his father, Mao Zedong. Mao Hanying grew up in the Soviet Union and served in the Red Army during World War II, witnessing the fall of Berlin in 1945.

One common question about the Korean War is why the Chinese entered the war as ‘volunteers’ instead of under the remit of the PLA. This was because Mao was keen to avoid the legal and political complications of a direct declaration of war between China and the United States, by hiding behind the façade of the term ‘volunteers’ to fight a proxy war.

Another common belief held by Western veterans and historians is that the Chinese won the early battles by applying the sheer weight of superior numbers of soldiers and unending waves of infantry charges until they overwhelmed the defenders. Was this a Chinese tactic? The authors found no such evidence from Chinese archives. The desire to close with the enemy as fast as possible was primarily driven by the limitations of Chinese weaponry, mostly short-range weapons, and mitigated the effectiveness of the Americans’ long-range firepower.

UNC veterans often recall the use of bugles and whistles as a terror weapon, a sound that strikes fear into many UNC soldiers. Did the Chinese deliberately use sound as a psychological weapon? From what the Chinese documents tell us, the use of such methods was how the poorly equipped Chinese compensated for the lack of wireless communications and was never intended to strike fear into the UNC troops.

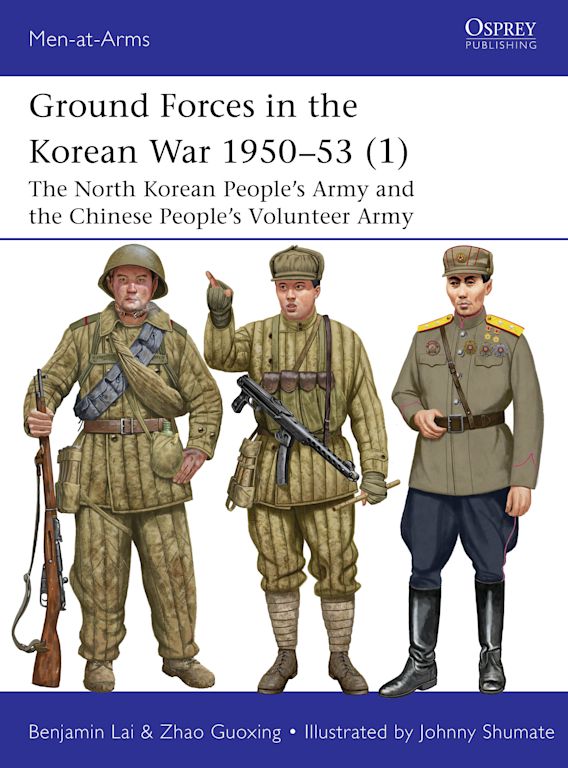

After the KPA collapsed in late 1950, the Chinese shouldered the major part of fighting the war, making all notable tactical and strategic decisions thereafter. Focusing on the North Korean and Chinese troops who fought in the Korean War, this new Men-at-Arms title briefly outlines how the Chinese remember the conflict and presents many little-known facts about it for the first time in English. It is a must-read for all who are interested in the Forgotten War, the first Hot War of the Cold War.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment