’Proklamasi

Kami bangsa Indonesia dengan ini menjatakan kemerdekaan Indonesia. Hal2 jang mengenai pemindahan kekoeasaan d.l.l., diselenggarakan dengan tjara seksama dan dalam tempoh jang sesingkat-singkatnja.

Djakarta, 17-8-’05

Wakil2 bangsa Indonesia

Soekarno, Hatta’

’Proclamation

We the people of Indonesia hereby declare the independence of Indonesia. Matters concerning the transfer of power and other matters will be executed in an orderly manner and in the shortest possible time.

Jakarta, 17-8-’05[1]

In the name of the Indonesian people,

Soekarno and Hatta’

With these historic words, Soekarno and Mohammed Hatta, nationalist leaders of Indonesia, declared Indonesian independence on 17 August, 1945, and a new independent state was born. At the time Indonesia was still largely occupied by Japan and its independence not recognized by the Netherlands (its colonizer pre-1942). What followed was a diplomatic and military struggle which ended in 1949 when the Netherlands recognized Indonesian independence. At the root of this political and military conflict, was a struggle for the loyalty of the population with both Indonesia and the Netherlands each offering a political alternative. How did this struggle play out?

After the proclamation, Indonesia seized the political initiative and took its future into its own hands.[2] In the days and months following the proclamation, Indonesian nationalists (Republicans) took possession of the existing governing bodies in Java and Sumatra. The Indonesian police had not been disarmed by the Japanese occupying army and passed into Republican service in September and October.[3] The Japanese had disarmed Indonesian auxiliaries so the young Republic did not have its own army. Locally and regionally, however, the Indonesians formed the so-called ‘People's Security Services’. These fell under local and regional administrative bodies. In several rounds, the central government attempted to reorganize and professionalize these organizations into a centrally directed military organization, a laborious process which would take years. Even so, the army always maintained a certain independence from its political leadership.

In addition to the Republican army, numerous irregular armed groups with diverse political agendas were active. The Republic thus formed an independent Indonesian state with a functioning administrative apparatus with home-grown armed bodies. It offered an attractive and inspiring alternative using the slogan: Merdeka! (Freedom!).

In 1945, the Netherlands prepared to take possession of the Netherlands East Indies again. It was aware that constitutional relations would have to be changed and that the process would be a top-down process under Dutch leadership, however, the reality proved otherwise. The Netherlands East Indies administration had lost all of its political initiative and was in an extremely unfavorable position. During the Japanese occupation, the Dutch administrative upper layer had been removed from its functions and interned; after three years of absence, it was not easy to return. The colonial government in the Outer Regions, the islands outside Java, Madoera and Sumatra, continued to build on the existing Dutch administrative structures that remained.In Java and Sumatra, it was significantly less successful. There it not only had to compete with the Republic, but also to rebuild its own administrative organization almost completely.

Until 1942, the colonial administration had maintained itself as an occupier with a system of control based on coercion, authority and enticement. The primary means of coercion were threats of violence by the KNIL (the colonial army) and/or the police. The colonial state had acquired authority through the colonized accepting its directives and had acquired a certain degree of legitimacy. With incentives, the colonial state sought above all the cooperation of indigenous elites: the traditional feudal chiefs. These were rewarded for their cooperation.[4]

After the defeat against Japan in 1942, this control system had passed into Japanese hands. In 1945 the Netherlands could not take back this system from the Japanese. There was a lack of resources: the KNIL was spread across Asia in Japanese POW camps and the police had passed into Japanese hands so coercive means were lacking. In terms of authority, the military defeat of 1942, the Japanese occupation and the internment of a large part of Europeans had seriously damaged the Dutch colonial administration's prestige and legitimacy. The old Indonesian administrative elite had also lost its significant influence during the Japanese occupation and was largely unwilling to cooperate. The involvement of Republican officials was initially Dutch policy. Their willingness to cooperate was low however. This also applied to large parts of the population. The incentives for cooperation were thus largely exhausted.

The problems of recolonization further increased because of a major shortage of administrative personnel (the living tools of empire). During the Japanese occupation, about a quarter of European civil servants had died. After their liberation, the oldest civil service officials were also dismissed. During the war, the influx of new civil servants had also been interrupted for years. In November 1948, there were 105 civil service officials compared to 230 on Java and Madoera in 1939. Due to the work required after the devastating Japanese occupation and the lack of cooperation, many executive tasks ended up being dealt with by the European administrative corps so administration had become largely European-based. The Netherlands Indies administration, therefore, had a crisis of legitimacy and an inability to penetrate Indonesian society. Both crises reinforced each other and made recolonization difficult, if not virtually impossible.[5]

These crises were also exacerbated by conflicting objectives at political level: the Netherlands had set itself the goal of restoring authority and territorial expansion on the one hand, and preparation for the independence of Indonesia on the other. Both objectives were difficult to combine.[6]

The construction of political and administrative structures in the Netherlands was further complicated by Republican opposition. The Republic deliberately turned against the attempts of the Dutch colonial government to (re)build its own state structures by maintaining Indonesian state structures in occupied territory in the form of a (mobile) shadow government, and by not cooperating economically. This non-cooperation was re-enforced by terrorizing people who were willing to cooperate with the Dutch and by the sabotage of Dutch economic reconstruction; a scorched-earth policy where Netherlands Indies money was destroyed. The goal was 'that the people recognize only the government of the Republic of Indonesia alone. This means that the people refuse to be colonized again.”[7] It was not the direct threat of kidnappings and/or assassinations but above all the risk of reprisals that made cooperation an absolute no-go for the Indonesian populace.[8]

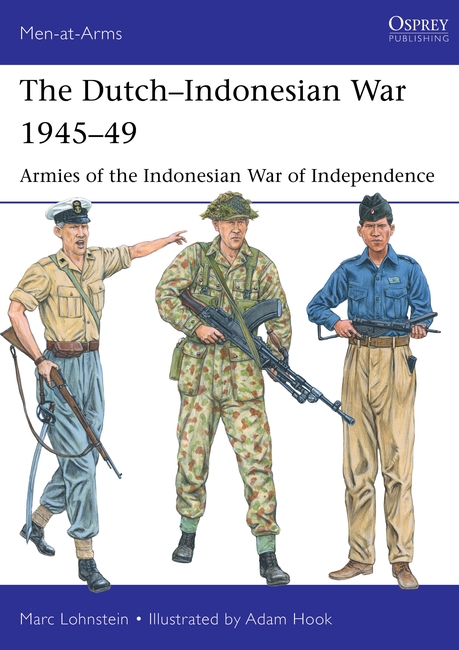

In MAA 550, The Dutch-Indonesian War 1945-49: Armies of the Indonesian War of Independence, I take a closer look at the military side of the Dutch-Indonesian conflict, and use rare photos and detailed illustrations of all the troops involved to present a comprehensive and detailed overview of the struggle.

[1] 2005 in Japanese era is 1945.

[2] Doorn, J.A.A. van en W.J. Hendrix, Ontsporing van geweld. Over het Nederlands/Indisch/Indonesisch conflict. Universitaire Pers Rotterdam 1970, 35-48.

[3] Anderson, Benedict R. O’G., Java in a Time of Revolution. Occupation and Resistence 1944-1946, Cornell University Press 1972, 85-88, 110-115 en 130; Remmelink, Militaire Spectator, 54-55 en Han Bing Siong, The Indonesian need of arms after the proclamation of independence, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 157 (2001) 4, Leiden, 801 en 810.

[4] Lammers, C.J., Vreemde overheersing. Bezetten en bezetting in sociologisch perspectief, Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 2005, 17-20 en 244-259.

[5] Zijlmans, Eindstrijd en Ondergang van de Indische bestuursdienst: Het corps binnenlands bestuur op Java 1945-1950, De Bataafsche Leeuw, Amsterdam/Dieren 1985, 129-130.

[6] Zijlmans, Eindstrijd, 293-296.

[7] Nasution, A.H., Fundamentals of Guerrilla Warfare, second edition, Seruling Masa Djakarta 1970, 19-20 en 109-111.

[8] Zijlmans, Eindstrijd, 74-76.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment