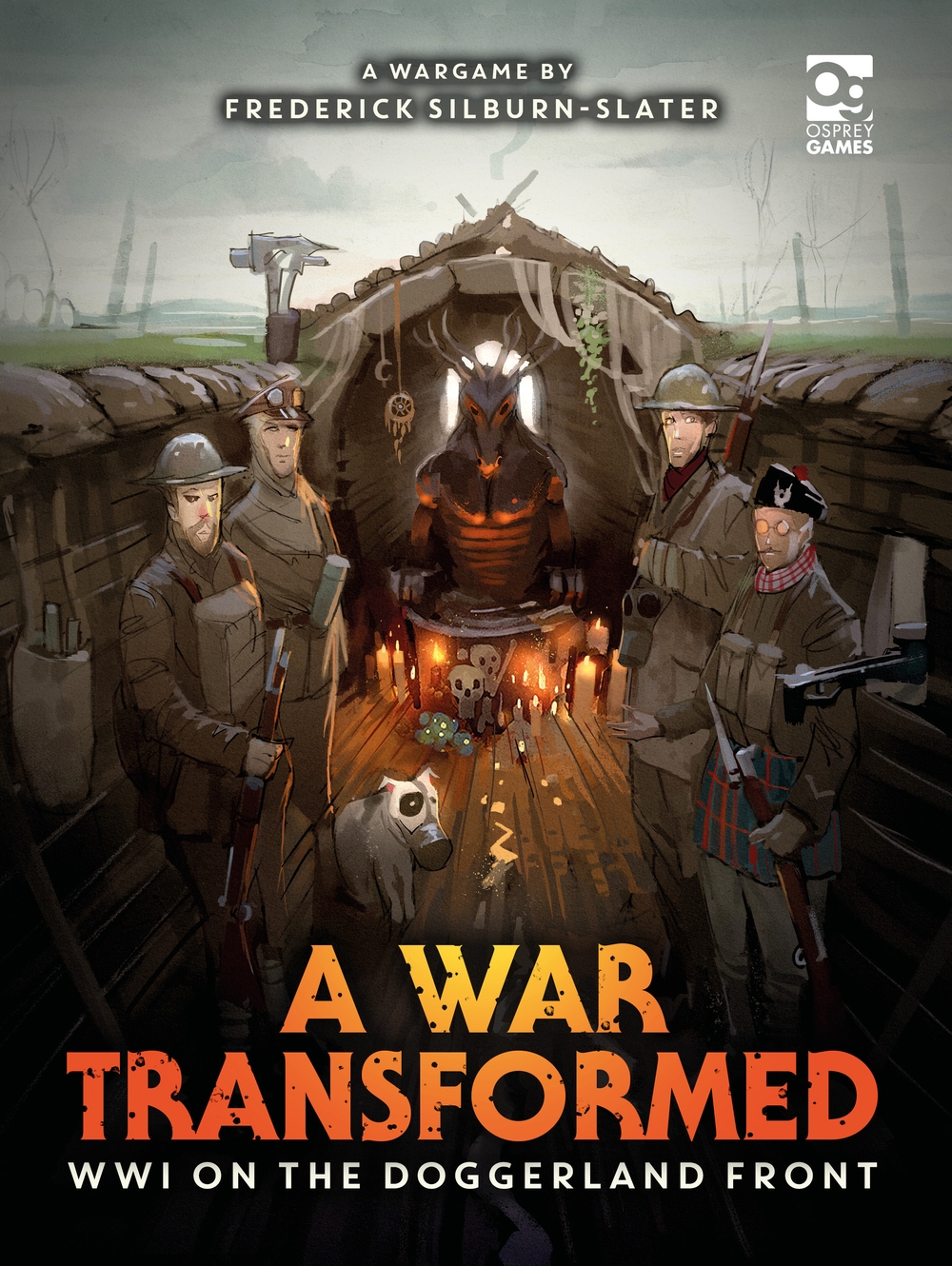

A War Transformed, our folk-horror Weird War One wargame, is out this month! We're kicking off a whole series of behind-the-scenes blogs with a deep-dive from author Frederick Silburn-Slater into the game's inspirations...

Rites of Spring

A girl has been chosen.

She stands alone, shivering with fear, a simple shift clinging to her youthful form. The music strikes up and her dance begins. Angular, discordant, primitive – her body gripped by something wild and uncontrollable. She whirls and spins, a crowd watching on, their attention rapt.

Will the gods accept her?

Her feet trace circles, faster and faster, in time with the shallow panting of her breath.

Will the Spring return? Will the winter end?

She leaps and dives, feet burning with the effort. The longer she dances, the more she slows, exhaustion sapping the strength of her limbs.

Her body gives way.

She collapses, dead as the frozen soil of deep winter. The crowd is silent, the gods appeased, as the last note fades to nothing... So began the Spring of 1913.

At the Theatre des Champs Elysees in Paris, the Ballet Russes debuted their newest piece, le Sacre du Printemps, or The Rite of Spring, a ballet set in the distant pagan past. The finale shows a young girl, chosen from the most beautiful maids in the village, dance herself to death in a brutal sacrifice to secure the fertility of the crops and the end of Winter. The reaction of the audience was described by some as a full riot: the bizarre choreography; the discordant, erratic music; the vivid costumes and sets – the effect was so great that it drove some guests into a violent frenzy.

It was hailed as both a masterpiece and a hideous mess, the product of delusional minds, a sick joke, but has since been recognised as a work of startling genius. It is considered by many to perfectly capture the spirit of the age, a time when Europe tottered on the precipice of a war that would sweep away the last vestiges of the pre-modern world. Conveniently for my purposes, its themes and inspirations closely align with those that are at the core of A War Transformed: art and culture in the decades leading up to the war, Folk Horror and environmental collapse.

A doomed, gilded age

As a rule, we write about what we know. The writers of wargames are no different. Perhaps talking about a ballet is an odd way to start an article about wargaming, but it wouldn’t be a strange way to talk about the massive upheavals in the cultural landscape of the early 20th century.

My background is in that cultural history. I spent most of my time at university studying the art, literature, and ideas of the last years of the Victorian age and the first years of the bold new century that came after. The Rite of Spring is part of that cultural maelstrom. It was a time when artists and writers looked at the great institutions of the world around them – church, patriotism, family – and called for much of it to be torn down. They advocated a return to the values of “primitive” man; emotional, spiritual and intuitive rather than rational, logical and ordered. Painters and sculptors looked to “primitive” cultures, emulating what they saw as their savagery. Many thinkers even welcomed the prospect of war as a great fire that would burn out the rot at the heart of the world…in some ways, they got their wish.

A War Transformed is inspired by this cultural moment and the artists and writers who inhabited it. The game draws its influences from those cultural pioneers who turned their back on a world of top hats and tail coats and embraced an older way of life governed by the instinctive, subconscious, and (in many cases) magical.

Sumer is icumen in!

As well as being a seminal work of modernism, The Rite of Spring could be called a formative piece of folk horror.

A cinematic and literary genre, folk horror finds the terror lurking in rural idylls. Its foundational works, films like The Wicker Man and The Blood on Satan’s Claw, have a narrative core that would have been familiar to the performers who danced in 1913: an isolated community; dark and unfamiliar beliefs; a sacrificial victim; mysterious rituals; and a violent, unpleasant death to propitiate ancient forces. It is a template followed in films like Midsommar, The Children of the Corn, and Apostle but first laid out by authors like Algernon Blackwood and Arthur Machan in the late 19th century.

Many see the birth of folk horror as coinciding with the counterculture movement and political uncertainties of the 1960s and 70s, but I think it is fair to look further back to the decades preceding (and immediately after) the Great War. Interest in witchcraft, pagan ritual, and old gods was as high in the late 19th and early 20th century as it has ever been. Not only were writers and poets plumbing folklore and myth for their subjects, but scholars like James Frazer and Margaret Murray were simultaneously investigating the (often spurious) origins of ritual and magical belief, whilst Freud and others tried to get to the root of fear, the supernatural and the uncanny. Their books were widely read and are deeply rooted in the fears and anxieties of the period. The idea that all of civilisation is just a thin veneer was a central preoccupation of people at the time. It is one which underpins folk horror as a genre – with the slightest pressure, people can be convinced to turn their backs on rationality and start herding their fellows into burning wicker effigies.

At the turn of the 20th century, truly rural places still existed. Many of the men who died in this most modern of wars had lived a life that would have been broadly familiar to even their most distant ancestors. They worked fields, raised livestock, and tended children just as they had always done. The cycles of life and death, the rhythms of the natural world, were still the chief concern for a great many people. For the rural communities of the time, the motivations, if not the methods, of the village elders who condemn that young girl to dance until she drops, or burns a man alive to make the fields fertile, would be well understood.

A War Transformed is inspired by the tropes of folk horror, its terrifying creatures, grisly sacrifices and terrible, inscrutable entities. It takes in the whole genre, from books and films to fanzines, music and aesthetics. It is a game of ancient spirits and wrathful ancient gods, where the forces of nature vie against machines.

There were giants in the earth…

At the heart of the narrative for A War Transformed is a climate catastrophe.

Ever since I was a child, I’ve been obsessed with palaeontology. The animals of the last ice age, or Pleistocene, are a particular fascination. It is a time when man existed alongside some of the most extraordinary creatures ever to walk the earth, and surely the most spectacular among them was the woolly mammoth. A huge shaggy elephant weighing some 8 tonnes, they inhabited the cold northern reaches of the world, possibly in herds numbering dozens of individuals. It is the quintessential ice age beast, with its long, thick coat and prehistoric look, so like a modern elephant and yet so markedly different. Their remains are often dredged up from the depths of the North Sea; a perplexing fact that elicits the obvious question: how did their remains come to be under water?

It no doubt would have puzzled the fishermen who hauled these bones from the murky waters between Britain and the Netherlands. Their vessels, Doggers, now give their name to the lost land that sank beneath the waves by a rapidly warming climate millennia ago – a huge fertile plain, home to those ancient mammoths, which connected the British Isles and Europe – Doggerland.

The idea of a sunken world, vanished for an eternity beneath the sea, is one with a long history. It has gained particular pertinence in a world threatened by climate change, and the submergence of Doggerland has parallels with the devastating forecasts of climate scientists in the modern day. Coinciding with a period of global warming, concurrent with a mass wave of extinction, it is a mirror of the present climate catastrophe. It is also its progenitor. With the retreat of the ice, man’s ascendancy began. Everything that we would recognise as “civilisation”, no matter how crude, begins to coalesce with this great shift. From farming to settlement building, humans started for the first time to manipulate the world to their own ends, changing animals, plants and the very landscape around them for the first time. The great changes wrought on our environment throughout history are a central inspiration for the cautionary tale at the heart of A War Transformed. In the last great climatic shift, the mammoths were squeezed out whilst our ancestors did very well, but it is unlikely we will be so lucky this time.

The world of A War Transformed

A War Transformed weaves these three separate threads together. Doggerland rises to the surface, its return heralding the beginning of another, altogether different climate catastrophe. It is the end of the age of man and the triumphant restoration of nature and the primordial forces of earth. Ecological collapse is central to the lexicon of folk horror. As the natural world on which we depend starts to unravel, people turn to ever more drastic means to stem the tide, cutting dark deals with supernatural forces to stay the inevitable just a little longer. Humankind must embrace its inner savagery to survive, turning its back on the rational and civilised and returning to the old gods, no matter what demands they make…

A War Transformed is out 28th September in the UK and 31st October in the US.

And watch this space for more A War Transformed content on our blog - with the first of three short stories by the author next Tuesday, and a look at the game's mechanics next Thursday...

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment