We return to the world of A War Transformed, with our second short story from author Frederick Silburn-Slater. Read on for more Folk Horror and Weird War goodness...

The Hunter

The buckets drop to the floor in front of me with a heavy clank. A dense noise, grave and ominous.

Crude iron nails clatter as they spill onto the stone floor. Gingerly, I reach for a handful, avoiding the sharp points. I juggle them in my hand briefly, a gesture of estimation: a conscious imitation of a street trader judging the quality of goods. It feels powerful, decisive – as though I am the sort who could judge the worth of iron by weight alone and not some soft professor’s son.

The nails are cold, with a menacing gravity.

“Have your fill,” the captain shouts, “though I doubt they shall do us much good.”

We’ve been commanded north to bolster the forces there, each day passing through bombed-out villages and towns, their names strangely familiar. After the events of The Shattering, as the moon fell out of its orbit, the sea has receded. We were taken off guard as a new front opened there. Now it seems that we are doomed to a mad scramble, vying to overtake one another, rushing headlong towards the water, even as it retreats.

I watch the impassive old Breton to my right. His rough-hewn face calls to mind the great statues of primitive gods we saw that day, some years ago.

You were staying for the summer – my cousin from Germany. Father had taken us into the city to see the exhibition he had been working on, long-forgotten treasures from beneath earth, the savage past revived on Paris’ left bank. How we marvelled at them; two young boys struck dumb in the presence of those ancient gods. We were transported, whisked from the cramped halls of the gallery to some ancient temple, a place of subterranean chambers and primal rites. Those great stone forms were so alien, as though carved not in the likeness of men, but a long dead race of giants: survivors from a time before humanity.

Another bucket clangs to the floor and breaks off my remembrance. The Breton’s hands, massive as they are, gingerly carve into the butt of his rifle with a nail’s point – intricate symbols, hieroglyphs radiating like the spokes of a wheel. A witch’s signs. I try to commit them to memory in the hopes of imitating them. Do they hold some power? If so, perhaps he will live, though I doubt it somehow. The captain has it right. No scratchings or trinkets will save us in this new world, or deliver us from its horrors.

I knot three nails through the cord about my neck. They join, uneasily, the simple cross my mother gave me that summer of 1914, the year this war cut our family in two. When you went to your duty, and I to mine.

I wonder whether you still live – so many died that first August, continue to die each day. Perhaps you fell with them then, or will tomorrow? Have you lived to see this new world of ours, those same old gods we saw that day in Paris come again as flesh and blood?

I stay awake to watch the setting sun. In the distance, some way off, is the silhouette of a man, boldly black against the burning sun. He is mounted, a lance resting lazily against his shoulder. Both man and horse stand still, surveying, like a hunter who has spotted his prey. He is not one of ours. Could he be a German scout, reporting on our movements? We know that they are nearby, maybe just the other side of the horizon, keeping time with us – making the same mad dash to the sea.

I hear dogs barking in the distance as I watch him – a strange sound, so close to the front. They must be stray mutts following our wake, stealing the scraps we leave behind in our hurried march.

He pulls at the reins and starts away. I wish him a silent goodbye and turn myself, descending into the cellar of some ruined farmhouse in search of sleep.

I wonder if I shall survive the night, or be entombed by some stray shell… I smile to think of it. Perhaps they will they dig me up, a thousand generations hence, to be gawked at by little boys on the Left Bank.

******************************

I awake – alive, unburied.

In the darkness of the cellar I turn the nails in my hand, running my fingers over their beaten heads like the beads of a rosary. I lie in that barren room, as quiet and cold as a crypt.

I try to bring to mind better times, beckon the warmth of memory to enliven the gloom. I think of that summer holiday we had shared, the year after you joined us in Paris – a pilgrimage to a far-flung corner of France for some dig or other. My father on his hands and knees, his trowel scratching away to reveal the secrets of the earth. How we, an unwelcome distraction to the academics in their trenches, were slipped a few sous and sent off to explore: field, forest, or town, they did not care.

We headed away from the tents and trestles of the dig site, off towards the great precinct of standing stones which had drawn my father to that place. We talked of school, the books we read, of friends and secrets, following the great lines of standing stones laid down scores of centuries before. I feel again the blistering heat of that day, walking beside those granite sentinels, beating the bounds of their serried ranks – mile after mile, across fields and meadows.

Eventually the summer’s sun defeated us, and we found refuge in the shade of a grove – a ring of oak trees encircling a curious hill. I tumbled into exhausted sleep, cradled in the embrace of a great tree’s roots, the sunlight drifting lazily through the leaves above. When I awoke, the sun lay low in the sky, and I found you changed – agitated, manic. You spoke of visions, a barrow, lying there beneath the earth. You talked in hushed and frantic whispers of the great chamber under our feet – tomb to the ancient god of this place, a hunter with steed, spear and a pack of braying, snapping hounds. A fire burned in your eyes as you described a wild hunt, unleashed into the night. That lordly hunter, risen again, riding at the fore, driving all before him.

We returned at dusk to the house my father had rented. You seemed withdrawn somehow. What secrets had that dark god whispered to you? You slept soundly, but I found no peace that night.

******************************

I hear shouted orders, the grunting of my bunkmates as they stir tired limbs, weighed down with the heaviness of sleep. I shake free of my remembrance and the day begins. A cook-fire sputters and crackles into life, the heartening smell of hot grease wafting from it. Far off, in the distance, the low rumble of shells tells us that we are drawing closer, but above the ominous growl of artillery, the sharp sound of barking dogs rings through our hasty bivouac. Some old man hunting truffles? Whatever he seeks he will not find it here. This place knows only death.

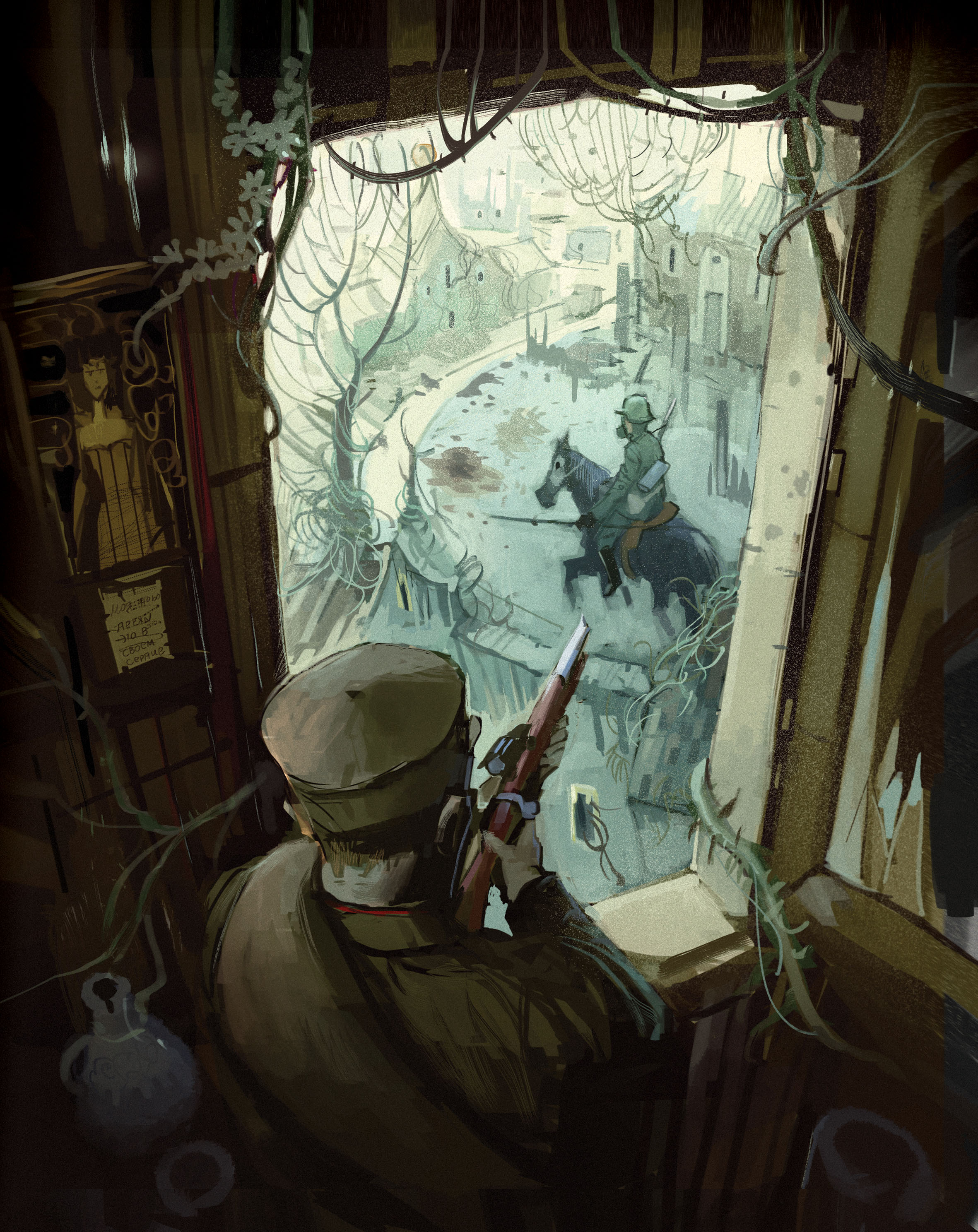

We march and march and march. I glance up, occasionally, and notice the black speck that follows our every step. The silent Ulan marks his constant vigil.

At the end of the day, another ruined house awaits me. I feel I know it as I pass through the doorway. Perhaps I imagine this familiarity. We have passed through so much country, our progress measured in the splintered remains of villages, their humanity stripped away, trampled beneath hobnailed boots, hooves and caterpillar tracks. They all look the same.

As I lay down, I hear dogs barking in the distance – a pack of strays I think, their masters gone, run off to some safe haven, or else buried under all this rubble by the torrent of shells.

******************************

I awake drenched in sweat, panting – as though I have run for many miles. The dawn has not yet broken, and the shattered remains of the room in which I sleep is icy-cold. I fumble with the kerned knob of a lamp and the wick rises hesitantly, like a head lifted above the parapet of a trench. As I strike a precious match, I hope that the wick has taken some warmth from the room – though only the pallid, sickly heat of a dozen sleeping men is to be had. The flame takes, casting a glow of tender, golden light through the stygian darkness.

I saw the rider in my dreams, that hunter on the horizon. He had your face, cheeks and brow anointed with the lifeblood of his quarry – a crown of bone and antler weighing heavy on his gory head. He looked at me, but the eyes were not yours – they were black as pitch, gimlet-sharp, shining in the gloom. All around his feet were a pack of snapping hounds, leaping and biting at the air.

I rise to sit in the doorway, the cold air of the night burning at my fingers as I gulp down some tinned mush. I think of your last visit, that febrile spring of 1914. The sudden patriotism that had gripped my father turned our breakfasts together frosty with contempt. He needled you each morning as my mother sighed, pleading for some peace. You defended your country, even as he read aloud the daily outrages printed in the newspaper.

I think of how you left, without a word, just one week into a two month stay. The letter on the sideboard the only trace of your existence, the lone artefact of a time when we were bonded by blood, by friendship. You had gone to fight for the honour of your fatherland. You wrote of fate, strength, devotion, the destiny of the German race. The weight of centuries bore down on you – you could not refuse the call.

******************************

My reverie is broken by a whirring screech, followed a moment later by blinding, searing heat. I feel an indescribable pain as all around me the world bursts into sudden light, a deafening roar, continuous waves that beat against my ears. I lie, prostrate and unmoving, for what feels like an eternity.

Gradually, I feel some strength returning to my limbs. My fingers move – sluggish, but serviceable. I try my legs, wriggling forward on my belly, scribing a line in the dust and pulverised remains of the walls under which we had sheltered.

A shell. A big one. I think of my fellows with whom I shared the last few hours. How many have survived?

I hear, dimly, the clamour of shouting men, the sound of rubble clearing, beams cast aside – it is faint, far off, muffled. I must try to free myself, escape this bedlam of choking dust and cordite stench. I crawl beneath a low arch set in the stone wall ahead, a half-buried window. The lintel tears at my back as I pass beneath, stomach pressed against the iron-hard, frosty dirt. My breath turns to vapour in the frigid air, obscuring my vision as I crawl out, emerging, blood-slicked and filth-caked, as though from the womb of hell.

I struggle to my feet, surrounded by blinding smoke. Still the deafening roar fills my ears, a curious ringing that sounds in snatches without rhythm or pattern, as though I am submerged. A red glow in the distance, a lantern perhaps? I stumble towards it calling out names, vainly hoping to feel a hand at my shoulder, see a kind face before me. I stagger in the direction of the light, shouting above the din in my ears. Time passes, though I seem no closer. I reach my hand out and steady myself against a great stone, standing tall above the grass.

I walk for hours, with no sign of anyone, the ranks of standing stones my only companions. Beneath my feet I hear the crackle of wheat stubble. My hearing is returning, slowly, though my thoughts still swim thickly through my mind.

My stomach tightens as I realise the source of the dreadful sound that has been following me, edging ever closer as I stumble blindly in the night – it is the braying of hounds, perhaps a dozen. A hunter’s pack. Their barks are maddening, tearing at my ears like snapping jaws. I quicken my stride, trying to outpace them, but the sound comes on louder and louder, until I can discern nothing else. I clasp my hands to the side of my head and break into a run, heedless of all obstacles, stumbling and thrashing through the night, bumping between the stones, harried by that terrible chorus.

I pass beneath a twisted arch of oak boughs. The trees that form the great ring are smashed to pieces, their grubbed-up roots stand proud above the earth, freshly turned by some shell. I stumble over them, clambering up the great hill. Reaching its summit, I look down into the cavernous mouth before me – a great hollow in the earth, laid bare by the explosive power of modern artillery. It is the tomb you saw that day, when the hunter first appeared in your visions.

Looking over my shoulder, I see a shape moving behind the ring of splintered trees, black and huge. It rushes towards me, veiled by the thick smoke all around, weaving between the gnarled trunks. I hear the thunder of a galloping horse, the pounding beat of hooves against the frozen ground, accompanied still by the ghastly braying of those hounds.

They are upon me now. I feel their hot breath, hear the snapping of their jaws.

I fall to the ground before the great maw in the earth, encircled, brought to bay. My ragged lungs heave, gulping cold air as my muscles shiver, exhausted by the chase. I roll to my back, the entrance to the barrow just behind me.

The sky above me blazes with fiery dawn, the point of the lance before my eyes reflecting the crimson brilliance of the rising sun.

The hunter gazes down as the beasts tear at my flesh, impassive as stone – your face a livid mask of primal splendour.

A War Transformed is out 28th September in the UK and 31st October in the US.

The final design diary, on world-building, is out this Thursday,

and watch this space for one last short story from the author as well...

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment