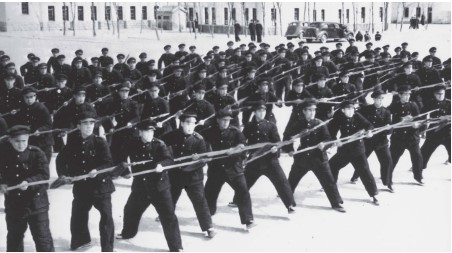

Hu Zongnan's troops in training. Despite betraying the Nationalists over Yanan, Hu continued to profess loyalty to Chiang and to lead a Nationalist army. (Philip Jowett).

On the blog today, author Michael Lynch considers the enduring significance of the Civil War.

There are episodes in history that have a direct and immediate bearing on today’s international crises. The Chinese Civil War of 1945–49 is one of those. In writing a study of those tumultuous years, I became increasingly conscious that I was examining a series of events and issues that, though they belonged to the past, were of the utmost significance for the present. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is one of the world’s great powers, arguably the greatest. What its leaders think and how they behave affects the rest of the world in the profoundest of ways.

The current Chinese leaders’ perception of the world and the PRC’s role in it is a consequence of a number of developments, the central one being the Civil War, a struggle in which the Communist Party (CCP) under Mao Zedong defeated its internal enemies, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists (GMD), and rejected the attempts of both the Soviet Union and the USA to impose themselves on the struggle. The outcome of Mao’s victory was the establishment of China as an independent state. That is why the Civil War is to be regarded as the major formative event in modern Chinese history. Without the Communists’ victory in the war, all that followed under Mao and his successors down to and including Xi Jinping would not have occurred. In short, without the Civil War there would be no Xi Jinping and no Chinese world dominance.

The Civil War is thus of momentous consequence for our times. There is one particular legacy of the war that continues to cast a perilous shadow – Taiwan, an issue that singly is the greatest threat to world peace in today’s world. When Chiang Kai-shek was driven from the mainland after his defeat at the hands of Mao’s Communists in 1949, it was not the end of the story. Having fled with the remnant of his forces to the offshore island of Taiwan (Formosa), Chiang proceed to create an alternative Chinese Republic which claimed to be the representative of the true China. Mao’s counter claim was that Nationalist Taiwan was merely a rebellious province, which the PRC was entitled to invade and re-occupy at any time it chose. Backed by the USA, which committed itself to the defence of the island as part of America’s Cold War strategy, Chiang’s Nationalists were able to resist. That resistance has continued from 1949 to the present. The critical question that remains unresolved is whether the PRC is prepared to carry out its continually repeated threat to take Taiwan by force, and whether in that event, the USA would intervene militarily in keeping with its longstanding promise to come to the aid of the Taiwanese.

To put all this in historical perspective and estimate the War’s enduring significance, I offer the following observations:

- The Chinese Civil War witnessed appalling carnage; the Nationalists lost over one and a half million men, the Communists approaching a quarter of a million. To those totals can be added another five million, the number of Chinese civilians who died from the famine and disruption that accompanied the war or who were the victims of the terror tactics used deliberately by both sides.

- The conflict was not a struggle about principle and ideology, though that was often the language in which it was couched. Instead, it was a naked struggle for military supremacy. Having achieved power by breaking its military and political adversaries, the CCP under Mao proceeded to establish a new Chinese state whose hallmarks were its readiness to coerce its people into line and to destroy those who opposed its rule. The guiding concept to which Mao adhered was that politics, like war, was a constant conflict. In that regard it was a continuation of the dialectical pattern of Chinese thought. His oft-quoted mantra that ‘all power grows out of the barrel of a gun’ was for him to be as much a truism in peacetime as it had been in war.

- The Chinese Civil War was much more than a parenthesis to the larger Cold War. Indeed, what happened in China between 1946 and 1949 helped shape the Cold War. It is legitimate to speculate that without Mao’s victory in 1949, the United States would not have developed its aggressive response to what it saw as the creation of a Sino-Soviet Communist monolith. The Soviet Union without China as an ideological ally would have had to be far more circumspect in its approach to international relations, with the result that hostility between East and West would not have intensified in the way that it did. Had China not gone Communist in 1949, there would have been no Korean War in 1950 and no Vietnam War in the 1960s.

- Important though Mao’s victory was in Cold War terms, its significance goes further. Viewed from an Eastern perspective, the Chinese struggle was of huge consequence to Asia. It led to the creation of modern China – a nation structured on the basis of not only a rejection of many Western values, but also a rejection of Communist ones as represented by the Soviet Union. There is also a sense in which the Civil War freed China to follow its own path, which is what Mao meant when in 1949, at the climax of his military triumph, he declared that ‘China has stood up.’ Achieved in the face of both American and Soviet opposition, the Communist victory over the Nationalists marked a formative stage in the rise of China as a world power, seemingly destined to become the most influential force in international affairs in the 21st century.

Mao Zedong is rightly remembered in the popular imagination as an extraordinary political figure who, after 1949, recreated China as a nation in his own image. But it must not be forgotten that his control of China was a product of his success in the field. His political ideas were obviously of intrinsic importance, but they would have counted for little had he not won the Civil War; and ideology does not win wars unless it can be translated into realistic and practical action. - The legacy for the victorious CCP was the belief that the methods and strategy that had won the Civil War applied also to the politics of peacetime. It was the memory of the military victory achieved between 1945 and 1949 that inspired Mao’s adoption of coercion as the principal means of running the new China that he had brought into being.

- Yet a final irony intrudes. China became a great power not because of Mao but in spite of him. For all his ability to create a nation dedicated to a political ideal, the power of China in the 21st century rests not on its politics but its economics. There is a sense in which Chiang Kai-shek proved the final victor. He and his successors’ development of Taiwan as one of the ‘tiger economies’ of the second half of the 20th century became the unacknowledged capitalist model on which Mao’s successors, abandoning his dated policies, began to build modern China.

There is also a sense in which the Chinese Civil War has not ended; no formal peace treaty or agreement has ever been made. The conflict that began in the era of the Cold War has outlived that larger struggle. The two Chinese states that emerged from the Civil War, the PRC and Taiwan, have followed very different paths in their subsequent development, but each side continues to claim that it alone is the legitimate government of the whole of China. In the third decade of the 21st century, the issues over which the Civil War was fought 70 years earlier have still to be resolved. Xi Jinping, PRC leader since 2012, has repeatedly restated the right of the PRC to reclaim Taiwan for the mainland, by military invasion if necessary. Therein lies a direct link between the war of 1945–49 and the current threat to the international order and world peace.

Michael Lynch, November 2021

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment