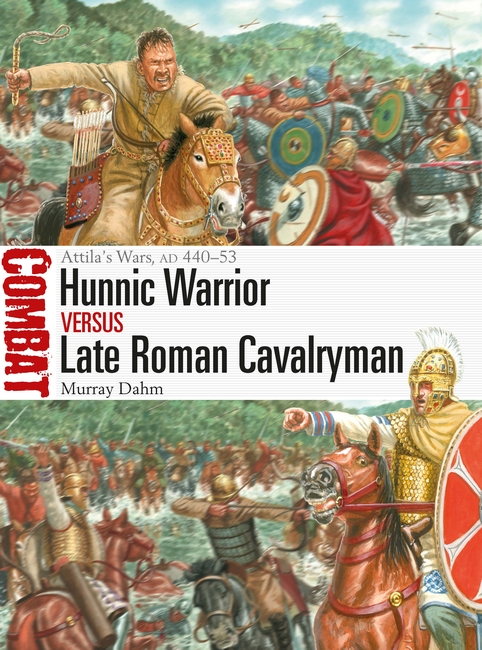

On the blog today, Murray Dahm, author of CBT 67 Hunnic Warrior vs Late Roman Cavalryman gives us an overview of The Battle of Catalaunians Plains.

The Battle of Catalaunians Plains – when is a plain not a plain? The famous battle between Attila the Hun and Flavius Aetius in AD 451 was fought, it seems, over a ridge.

The name of the battle of the Catalaunian Plains has become the most dominant one for the climactic meeting of Attila’s Huns and a vast alliance of Romans, Visigoths, Franks and others joined to oppose him in AD 451. There were, however, many other names by which the battle was known; Catalaunian Fields, Campus Mauriacus, locus Mauriacus (locus meaning, rather unhelpfully, ‘location’), Maurica, Châlons, Troyes. All of these alternate names are not helped by the fact that we do not know the precise location of the battle and much ink has been spilt arguing for one location or another.

We know that Attila had rampaged across Germany and Gaul, sacking many towns. Jordanes tells us that Attila’s horde of rampaging Huns had 500,000 men. Very few scholars believe that number, but there were enough men with Attila (and they had wrought such destruction all over the Roman Empire in the previous ten years) that it was large enough to create the perception of Hunnic hordes we still have. Attila reached Orléans and there, either just before he breached the walls or even as he was breaching them, the allied army of the supreme Roman general Flavius Aetius (the comes et magister utriusque militiae) and Visigothic King Theodoric came into view. There were other allies too: Alans, Franks, Sarmatians, Armoricans, Liticians, Burgundians, Saxons, Riparians, Olibriones, Riparioli and Briones. Some of these names defy identification but this large number of allies were probably amassed to at least try and match Attila’s numbers. Attila had allies of his own – Ostrogoths and Gepids – although Sidonius names a whole array of peoples (several of them fictional or from myth): Gepids, Rugi, Sciri, Neuri, Bastarnae, Thuringi, Bructeri, Franks and Burgundians. This was to be an enormous meeting of hostile peoples, perhaps the largest battle the ancient world ever saw.

Attila chose to retire from Orléans, probably towards Tricasses (modern Troyes, France) on the River Seine. As he prepared to cross the river by the bridge there, the forces of Aëtius and Theodoric caught up to him; they had followed him from Orléans. Other sources, however, give the location of the battle as close to Metz, or the Mauriac plain, even on the Loire or Danube. There was probably some celebrity in being the site of the battle and several candidates emerged. Paris, an unimportant town in 451, developed its own mythology of how it was saved from Attila by St Genevieve – but contemporary sources do not name it as a target. Modern scholars have argued incessantly over their favoured location, north, east or west of Troyes. The ancient town of Catalaunum is now Châlons-en-Champagne on the River Marne (hence the name the Battle of Châlons).

Our best account of the wars with Attila – although there are many which need to be sifted through – is the 6th-century historian Jordanes, who wrote two works that are extremely useful to us. Known as the Getica, the De origine actibusque getarum (‘On the Origin and Deeds of the Goths’) traces the history of the Goths but also includes Hunnic history. Jordanes used the eyewitness Priscus of Panium as a source although some of his material seems to go further than Priscus does. Jordanes also wrote a Romana, a short history of the most noteworthy events in Rome’s history down to AD 552. Jordanes’ account of the battle in the Getica is the most complete we possess even though his details differ from other accounts and several modern authors do not follow it. Most importantly, Jordanes makes the crux of the entire battle the contest for a ridge. He describes the battlefield as a ‘plain rising by a sharp slope to a ridge’. Jordanes tells us that the Huns seized the right side of the ridge and the Visigoths the left, with the crest untaken; it would be there, at the crest, that the battle was decided. Both Aëtius and Attila realized that control of the crest would be crucial to the battle and, in the race to secure it, the cavalry of Aetius and Thorismund (Theodoric’s son and heir) reached it first and there they held off successive Hun cavalry attacks. The Huns tried again and again to take the ridge, Attila himself leading charges seeing that his personal command was necessary. The Romans and Visigoths on the crest also needed reinforcements and Theodoric led more Visigoths forward; in doing so he lost his life and Thorismund continued to fight not knowing he was now king. The battle began at 3pm on 20 June, close to the summer solstice, and fighting continued until nightfall, around 10pm; seven hours of continuous fighting. Only as night drew close did Attila break off his attacks and withdraw to his wagon laager. Confused fighting continued in the darkness – the allies pursued the retiring Huns but Thorismund pursued too keenly and got isolated in the Hun encampment and had to be rescued. Aëtius too got lost and isolated from his men – he spent the night in the Visigoth camp.

The battle has gone down as one of the most decisive in western history. This may not be strictly true as Attila remained a threat and invaded Italy in AD 452, plundering many cities in the north including Aquileia and Mediolanum (Milan). Catalaunian Plains was, however, certainly bloody. We are told of 300,000 casualties and Jordanes calls the battle the ‘graveyard of nations’. As it seems to have been primarily a cavalry battle, historians have sought for a flat plain on which the huge numbers of cavalry on both sides roamed. If we read our best sources closely, however, the battle was fought mainly for the control of a ridge. To find out exactly which ridge, you’ll have to get yourself a copy of CBT 67!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment