In today's blog post, we're looking at three fantastic pieces of artwork from three of our September 2022 titles. Let us know what you think in the comments section and, if you would like to see any artwork from any of our October titles, be sure to mention that too!

Artic Convoys: 1942: The Luftwaffe cuts Russia's lifeline by Mark Lardas.

Illustrated by Adam Tooby

After PQ-17 dispersed, the merchant ships’ escorts abandoned them under Admiralty orders to prevent the convoy from reforming. One captain, Lt Leo Gradwell, RNVR, commanding the antisubmarine trawler HMS Ayrshire, disregarded the order. Finding steamship Ironclad heading north, he began escorting it and the pair soon encountered Troubadour, another old Hog Islander, like Ironclad.

It joined them as Gradwell took his charges to the edge of the pack ice where they found another Hog Islander, Silver Sword, skirting the ice pack and which joined the other three ships. Gradwell led his unlikely convoy into the ice, breaking the way for the freighters until they were 25 miles into the ice pack and could go no further.

All three freighters were coal-burners, and Troubadour’s cargo included bunker coal, intended for Russia. It also carried a large quantity of white paint. Gradwell decided their best strategy would be to lie hidden in the ice long enough for the Germans to stop searching for ships from the scattered convoy. He ordered the boiler fires banked, both to save fuel and eliminate smoke.

To increase the ships’ concealment, Gradwell ordered Troubadour’s white paint distributed. Crews painted all visible metal surfaces white: Troubadour and Ayrshire enthusiastically slathered white paint on both sides of their ships, whereas Ironclad and Silver Sword only coated their starboard sides with paint, exposed as they were to searching Germans. Surfaces that could not be painted, such as hatch covers, were covered with white bedsheets and table linen.

Additionally, Troubadour and Ironside had deck cargoes of M-3 tanks which Gradwell authorized opened, and their guns manned. Their 37mm turret cannon would augment the ships’ antiaircraft batteries if they were discovered. German aircraft flew by them while they were so hidden, but missed seeing them.

The ships remained in the ice for three days, finally emerging on 7 July. By then, the hunt was dying down and Gradwell took his charges to Novaya Zemlya, from where they safely reached Arkhangelsk. Gradwell would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions. A barrister before the war, Gradwell resumed his profession at war’s end, ultimately becoming a magistrate.

This plate captures these survivors on 5 July, balanced between safety and peril. They are hidden in the ice, 20 miles in from the pack edge, and have camouflaged their ships with white paint, table linens and sheets. Their fires are banked, so they are making no smoke. In the distance a scouting German Blohm & Voss BV 138, a ‘flying clog’ due to its distinctive profile, reconnoitres along the edge of the ice, seeking ships sheltering there.

The men aboard the four ships hold their collective breaths. Will they be spotted? The crew of the BV 138 seek what they expect – ships hiding along the pack edge. They are probably tired, since it is a long trip from their Bodö anchorage to the summer ice limit, and never dream their prey is so deep into the ice pack. They fly on, never detecting what is hidden in plain sight

Requested by Adam C.

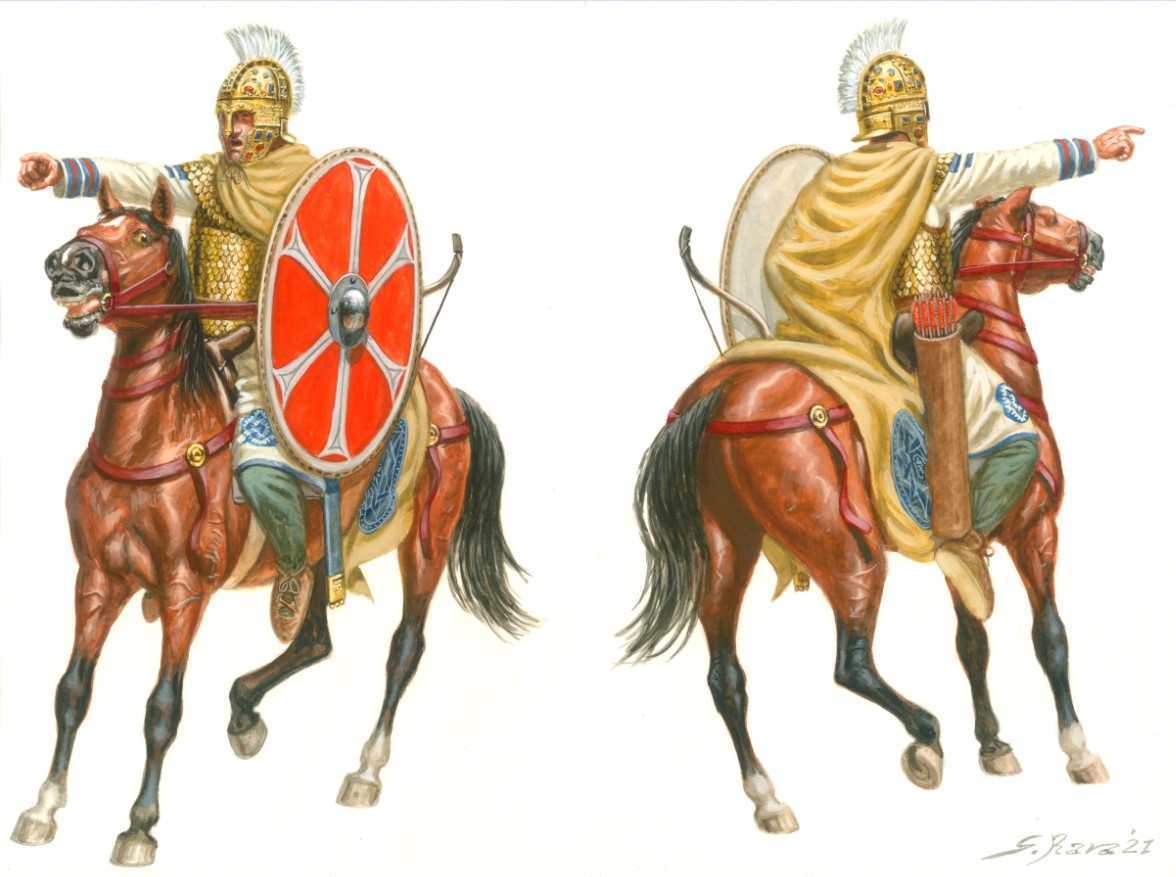

Hunnic Warrior vs Late Roman Cavalryman: Attila's Wars, AD 440-53 by Murray Dahm

Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava

Our cavalryman is armed with a bow and also wears a spatha at his left hip. He wears a typical long-sleeved decorated lined tunic and a cloak. He eschews greaves, but wears scale armour with a collar and a Berkasovo-type cavalry ridge-helmet. Despite its outwardly expensive appearance, most of the decorations are glass and the helmet is iron covered in silver-gilt. He is equipped with a quiver and carries his shield displaying the blazon of his unit. No shield designs for eastern cavalry units are depicted in the Notitia Dignitatum, so this shield design is taken from a (rare) tombstone of a cavalryman from the same unit (AE 1976, 00617) found at Tomis (modern-day Constanța, Romania) in 1913. His horse has a four-pommel saddle and wears no chamfron to cut down on weight.

Our best evidence of the junior officers in Roman armies of the 4th and 5th centuries comes from a speech of Jerome (Against John of Jerusalem 19), which lists the pay grades of various ranks; these pay grades may not be the same as the ranks themselves, however. The list is corroborated by a 5th-century edict issued by the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I (r. 527–65) in 534 (Codex JustinianusI.27.2:19-3). These pay grades, in order, were: tiro (‘recruit’), eques or pedes (‘cavalryman’ or ‘infantryman’), semissalis, circitor, biarchus, centenarius, ducenarius, senator, primicerius and tribunus. The standard pay for a cavalry semissalis, circitor, biarchus or centenarius was the same: one capitus (the equivalent of 20 solidi or one year’s horse fodder)

Requested by KAL9000

British/Commonwealth Cruiser vs Italian Cruiser: The Mediterranean 1940-43 by Angus Konstam

Illustrated by Ian Palmer

The Battle of Pantelleria, 15 June 1942.

By the summer of 1942, the Central Mediterranean was firmly controlled by the Axis. However, as the beleaguered island fortress of Malta was desperately short of supplies, the Admiralty agreed to send two small but well-protected convoys to Malta, one from Alexandria and the other from Gibraltar. The eastbound convoy, MW-4, sailed on 12 June. Two days later it was subjected to heavy air attacks as it entered the narrow strait between Sicily and the coast of Tunisia. These attacks continued the following day, 15 June, but this time these coincided with a surface attack spearheaded by Rear Admiral Da Zara’s 7th Cruiser Division. His force consisted of the light cruisers Eugenio di Savoia and Raimondo Montecuccoli and six destroyers. The convoy’s close escort of one old AA cruiser, five destroyers and four destroyer escorts was outnumbered and outgunned. Still, it laid smoke to cover the merchantmen, and fought back. In the running battle that followed, the destroyer Bedouin was sunk, Cairo and the destroyer Partridge damaged, and two merchant ships sunk, including a precious tanker. This shows the action soon after dawn at 0540hrs, when the Italian flagship Eugenio di Savoia and the Raimondo Montecuccoli (pictured here) first engaged Cairo, nine miles away to the west, on a parallel southerly course.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment