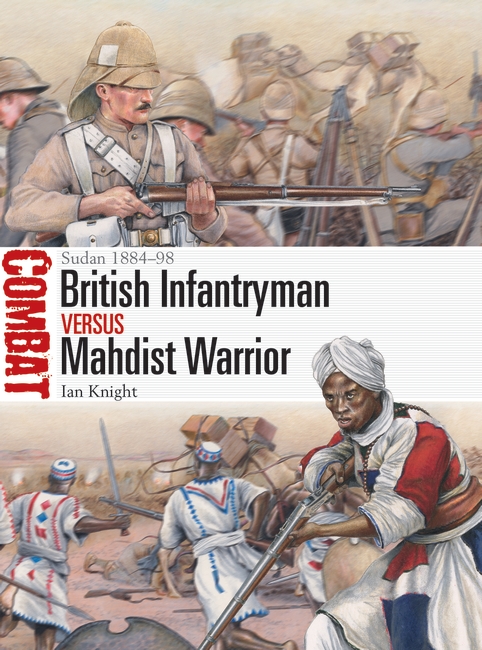

The upcoming Combat title British Infantryman vs Mahdist Warrior is a new study of the battles fought between Queen Victoria’s infantry and the formidable Mahdists in the Sudan, from the Gordon Relief Expedition of 1884–85 to the climactic battles in 1898. In today's blog post, author Ian Knight shares how this fantastic title came about.

I think anyone taking even a quick look at my titles for Osprey would be forgiven for thinking that the 19th-century British campaigns in the Sudan are not my usual turf, and for the most part, I have to own up to the fact that my speciality lies elsewhere (Zulus, if you haven’t noticed!). That said, I have made the odd digression into other British colonial campaigns, notably in the Men-at-Arms Queen Victoria’s Enemies sequence, which was designed to offer a counterpoint to Michael Barthorp’s British Army on Campaign sequence, and considers the various groups around the world who defended themselves against the rise of the British Empire. Of course such a grouping was much more arbitrary than its British counterpart, where the same Army was evolving to face different challenges around the world – the opposition was much more disparate involving very different and unconnected forces who were organized, armed and fought in very different ways in a wide variety of contrasting landscapes around the world.

Nevertheless, the experience of writing Queen Victoria’s Enemies did leave me with an awareness that, not only have Britain’s enemies of the period tended to be consigned to the superficiality generally accorded the losing side in history written by winners, but that there were nevertheless common threads between them. In each case the armed forces of those countries had to contend with facing an enemy that was technologically more powerful but was usually numerically inferior, and as a result they developed techniques which made the most of their familiarity with the terrain, and often quickly adapted Western technologies to turn against the invaders. Thus, during the New Zealand Wars the traditional Maori earthwork known as a pa, which was as old as Maori warfare, was quickly adapted to provide artillery-proof bunkers, and used to blunt British infantry attacks.

It’s always good to contribute a title to the Combat series but it’s not without its challenges – inherent in the approach is an analysis across a range of campaigning, showing how techniques, uniforms and weapons varied, and that requires an awful lot of research to be able to ‘compare and contrast’. I remember the thing which had intrigued me about the Sudan campaigns, though, and in a sense drew me into this title; some years ago Colonel Mike Snook – himself an author on Victorian military history – showed me a photograph of the grave of a British colonel, Fred Burnaby, who had been killed at Abu Klea, during the attempt to relieve Charles Gordon and the beleaguered garrison at Khartoum. Burnaby was something of an adventurer, a Boy’s Own hero renowned as much for crossing the Channel in a hot-air balloon and travelling through Central Asia as for his military career, and his last resting place is somehow fitting, a rugged pile of stones in a hot, bleak and inexpressibly lonely desert landscape. The questions Mike’s photos aroused in me are, in many ways, what my Combat volume is about: not only what on earth had brought Burnaby to such a spot, but also how had he got there – and how had an pre-industrial Sudanese army come very close, on that remote spot, to defeating the representatives of the world’s greatest super-power at the time?

The answer, of course, is that in waging wars at so many far-flung places around the world the British had to fight the terrain almost as much as the enemies they encountered there. In order to try to reach Khartoum, at the confluence of the Black and White Niles, in the heart of the Mahdist state in the Sudan, the British first had to pass through Egypt before striking out across the desert. Extraordinary – but in the end unsuccessful – attempts were made to prepare for the advance, including training detachments of infantry to act as Mounted Infantry but riding camels not horses, while access to water and methods to counter the heat were crucial factors in British planning. In this regard the terrain had to be defeated almost as much as the Mahdists themselves. Nevertheless, in 1885 the Mahdist movement was at the height of its success, and, although its forces were not as organized or well-equipped as they later became – they were still largely dependent upon enthusiastic attacks by non-professional adherents armed with close-quarter weapons – when the confrontation came it was when the British were most stretched and the Mahdists arguably at their most comfortable. Abu Klea was a close-run battle, and a series of minor mistakes on the part of the British commanders rendered the British square uncomfortably vulnerable – Burnaby was one of many casualties on the British side, and for a few brutal moments it looked as if the British square might break.

In the age of high Imperialism, the battles in the Sudan were often presented as being foregone conclusions but, as Burnaby’s fate testifies, that was never really the case – and by looking at the experience of the ordinary soldiers who fought on both sides in that harsh and unforgiving terrain I hope this volume reveals something of the difficulties both armies faced, the opposing forces’ strengths and limitations, and the sheer courage of the combatants on both sides.

British Infantryman vs Mahdist Warrior publishes next week. Preorder your copy now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment