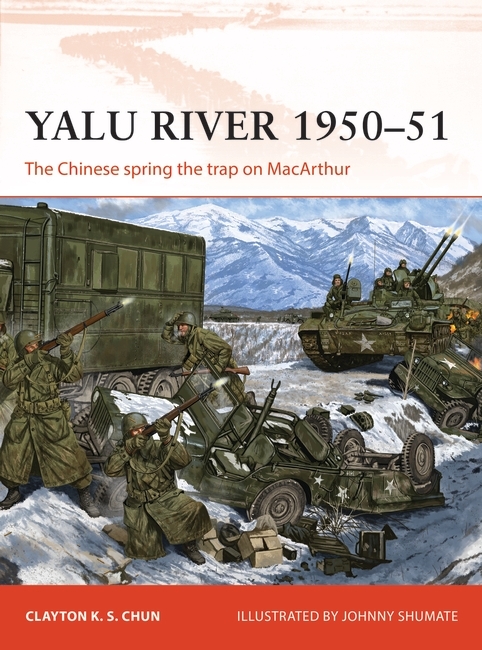

In today's blog post, Clayton K. S. Chun gives a brief overview of the Yalu campaign, the subject of his upcoming book, Yalu River 1950–51.

By early 1950, the South and North Korean governments were settling into an apparently peaceful co-existence. Like a bolt out of the blue, the North Korean People’s Army invaded the Republic of Korea in June. Within days, the North Koreans had smashed through the border, overwhelmed the South Korean military, and were on their way to achieve a total victory that would forcibly unify the Korean peninsula under a communist flag. A largely unprepared American ground force from Japan barely managed to halt the North Koreans at the Pusan Perimeter. American airpower was also able to help slow the advance, but more was needed.

General Douglas MacArthur, with a United Nations mandate, prepared to break through the Pusan Perimeter and force the North Koreans back to the 38th Parallel, the negotiated Korean border. The United Nations had only instructed MacArthur to restore the pre-war borders. MacArthur’s staff in Japan had a bolder plan. United States and South Korean forces would initiate operations among the western (and eventually the eastern) coastline and in Pusan to push the North Koreans out. Washington had started to mobilize for this fight and would also receive United Nations member military units. On the western coast, MacArthur would take a riskier gamble by conducting an amphibious invasion at Inchon, behind North Korean lines. Given the build-up of forces in Pusan with a breakout and the Inchon invasion, the North Koreans would be threatened with being cut-off and potentially destroyed. MacArthur’s plan succeeded. The North Koreans suffered massive casualties and had no option but to head across the 38th Parallel.

MacArthur appeared to have fulfilled the United Nations’ mandate. He had effectively repulsed the invasion and moved to the South Korean border. Questions arose to whether this was enough. Should MacArthur’s United Nations Command go deeper into North Korea and permanently settle the issue of the two Koreas? If he defeated the North Koreans, the United Nations could create one state under the Republic of Korea. If so, how would the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union react? Moscow had already entrenched along an “Iron Curtain” and had demonstrated their ability to challenge American and Western interests. The Berlin Blockade in 1948 and other actions showed that they would act. Would the proposed actions in Korea widen the war and initiate a global one? Would the Soviets now try to invade Western Europe? Similarly, Peiping had just forced the Nationalist Chinese government into exile in Formosa. Mao Zedong had a number of hostile neighbors across the Chinese border. The United States had the powerful Pacific Fleet and had bases in Japan, Guam, Okinawa, the Philippines. The British colony in Hong Kong and French forces in Indo-China also represented a threat. Now, an American-supported Republic of Korea would have military forces bordering its industrial heart in Manchuria. If North Korea fell, this would be a major threat to China’s security as they would be surrounded by enemies. Would China send forces to oppose MacArthur?

MacArthur and other American government agencies convinced President Harry Truman that neither the Chinese nor the Soviets would intervene. United Nations Command forces planned to drive north to the Chinese border on the Yalu River. To mitigate the appearance of an American takeover of North Korea only South Korean units would make the trek to the Yalu initially. Although driving north to the Yalu River had significant dangers, there were also some benefits. Truman could use this example to show Moscow and the rest of the Communist world that provocative actions did have a price to pay. In addition, this would “fix” the problem of Korea for the foreseeable future. Finally, Truman could answer critics that he was soft on communism that led to the loss of China to the “Reds.”

MacArthur’s highly successful Inchon invasion and offensive out of the Pusan Perimeter had shattered the North Koreans. The communists were on the run. Seoul was liberated and it seemed that there was little to stop MacArthur. Many on MacArthur’s staff felt that total victory was theirs for the taking and now was the time to act. United Nations Command forces seemed ready to steamroll over the North Koreans and end the war by December 1950.

Truman and Joint Chiefs of Staff provided MacArthur direction to head north and crush the North Koreans. However, some United Nations members questioned whether this was the best course of action since MacArthur had already achieved his prior mandate. Some in the Joint Chief of Staff had concerns about how such an action might force Moscow to take action elsewhere, like Europe. Still, MacArthur’s Eighth Army pressed north toward Pyongyang with minimal opposition. On the east coast, a ground advance from South Koreans and another amphibious landing by MacArthur’s X Corps appeared unstoppable.

By November 1950, all seemed well for MacArthur. Eighth Army did not appear to have any significant obstacles in its path with taking large swaths of North Korean territory. Similarly, X Corps marched up to the Chosin Reservoir and its units had made contact with the Yalu River. However, there were scattered reports of Chinese soldiers captured within the Eighth Army’s area of operations. Similarly, the American State Department had heard of Chinese warnings, via diplomats, about Peiping’s concerns about American forces crossing the 38th Parallel. If this occurred, the Chinese stated they would intervene in North Korea. Washington discounted these events. By late November, when MacArthur’s United Nations Command was to resume the final push into North Korea, the Chinese People’s Volunteers struck with overwhelming numbers. The Chinese mauled Eighth Army and X Corps. This strategic surprise shocked MacArthur, Washington, and the rest of the world. Instead of a victory, MacArthur just hoped to hang on and avoid a massive defeat. Retreat was the only viable option.

The Yalu Campaign significantly changed the war’s character and nature. Victory almost turned into defeat. This campaign eventually altered the face of the Koreas after a subsequent attritional fight lasting until 1953. The United Nations Command had to negotiate an armistice with Peiping and Pyongyang. Decisions made in the fall of 1950 still reverberate today and can help explain the issues in the Korean peninsula.

Order your copy of Yalu River 1950–51 to find out more.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment