Mark Lardas's fascinating title, Spanish Galleon vs English Galleon, explores the conflict between two formidable warship types of the Age of Discovery – the Spanish and English Galleon – as they battled for control of the Atlantic. In today's blog post, Mark explores how this fantastic book came about and gives a brief overview of the galleon.

I like writing Duels. My Duels typically span the years between the American Revolution and the American Civil War. A few years back, my editor, Nikolai Bogdanovic and I were kicking around ideas for a new Duel. He was trying to sell me on the idea of writing a Duel on battles between English and Spanish galleons during the age of Queen Elizabeth and King Phillip.

Initially reluctant, I fell in love with the idea. Francis Drake and the Golden Hind fighting the Cacafuego. Hawkins’s race-built galleons taking on the King of Spain’s Spanish Armada. The last fight of the Revenge. (“Sink me the ship, Master Gunner—sink her, split her in twain! / Fall into the hands of God, not into the hands of Spain!”) This is all cool stuff. I stifled my reluctance and agreed.

Why was I reluctant? Because to do a book on galleon battles, you have to write about galleons. I did not know what a galleon was.

El Galleon de Andelusia - a modern replica of a galleon.

(Library of Congress)

I knew about Anson taking the Manila Galleon. As a youth, I had adventure tales read about English Sea Dogs and a little later buccaneers fighting the Dons in galleons because there was no peace beyond the line. I visited El Galleon de Andelusia when it visited Galveston a few years back. Yet a galleon seemed a fantasy kind of ship – some old-time sailing warship tagged “galleon” by an author seeking to add interest to his tale. Or maybe like the Manila Galleon, an honorific added to a ship undertaking a specific mission.

I had seen that type of thing with frigates. Those writing sailing-era adventure novels set in the last half of the Age of Fighting Sail, set them on frigates, even if the frigate had 10 or 74 guns. Similarly, if it takes place in the first half of the Age of Fighting Sail, it has to involve galleons. Ships classified as galleons seemed to range from the 150 ton Golden Hind to 1500- ton Spanish monsters like San Pablo and San Felipe. Surely they could not be just one type of ship?

I am slightly wonky about sailing-ship types, especially those from the late Medieval to about 1525 (my preferred era for modeling), and from 1650 through the 1870s (my preferred era for wargaming). The galleon period, 1525 through 1625 (as it turned out) was a knowledge hole. As a not-so-famous author, I knew the answer was research. The opportunity to learn something new is a big reason I write books. (That, and the money. Sam Johnson said, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.”)

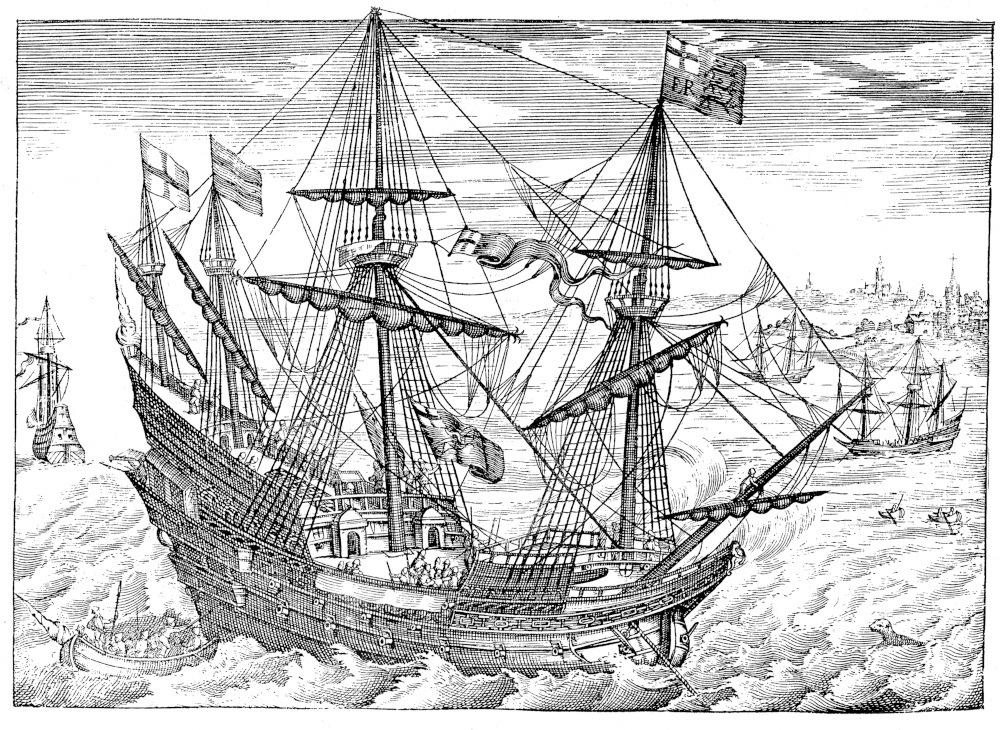

A romanticized attack on a Spanish galleon - typical of adventure fiction.

(Author's collection)

I soon discovered there was a type of ship called a galleon, and the type did span both the diminutive Golden Hind and the massive San Filipe. An outgrowth of the carrack, it eventually led to the modern sailing ship-of-war. The galleon is the sailing frigate grandfather.

The carrack, developed in the late fifteenth century, was the first ship intended to cross oceans. Prior to then, ships generally did not cross oceans. They sailed along coasts. The carrack was large enough to carry enough stores to cross the Atlantic Ocean with space left over to deliver and return cargoes. It had three or four masts, with square sails on the forward two masts and lateen sails on the after masts. Typically, the fore and main mast carried a course (lower sail) and a topsail. A square sail, called a spritsail, was mounted under the bowsprit. The spritsail, and lateen sails on the mizzen and bonaventure (as the fourth mast was called) masts were used to steer and turn the ship.

The carrack was frame built. The keel was laid, the structural frames were added and the ship planked after framing. Earlier ships were shell-built. The keel was added, the ship was planked, and then the frames were added fitting the planking. Shell-built ships were built keel-up, and then rolled over to frame. Frame-built ships were built keel down. They could be built larger than shell-built ships. They could also be built without the overlapping “clinker” planking required to give shell- built ships strength.

Frame-built ships used less wood per volume and were stronger than shell-built ships but required more sophisticated techniques. You had to be able to predict the shape of the ship before you built it.

Shell-built ships continued to be used (including the famous Dutch fluyte), but, by 1520, frame building was the future of naval architecture. Unfortunately, as warships, carracks had a problem – the location of the decks.

The main or lower deck of a carrack was typically only a few feet above the waterline. If you were only carrying cargo it may have been an advantage, keeping cargo lower in the hull, increasing stability. Then cannon came along. With carracks, if you put gunports in the lower deck you risked swamping the ship if opening them on the lee side. It happened with the Mary Rose, which was essentially a carrack. If you mounted them on the upper or weather deck, the guns had to be small and lightweight. Mounting big ship-killing guns that high made ships unstable.

At first shipboard cannon were seen as adjuncts to boarding battles, substituting for archers and crossbowmen. As artillery grew more common, more reliable and larger in the early 1500s, some forward-thinking naval types began realizing heavy artillery could be useful in a sea fight.

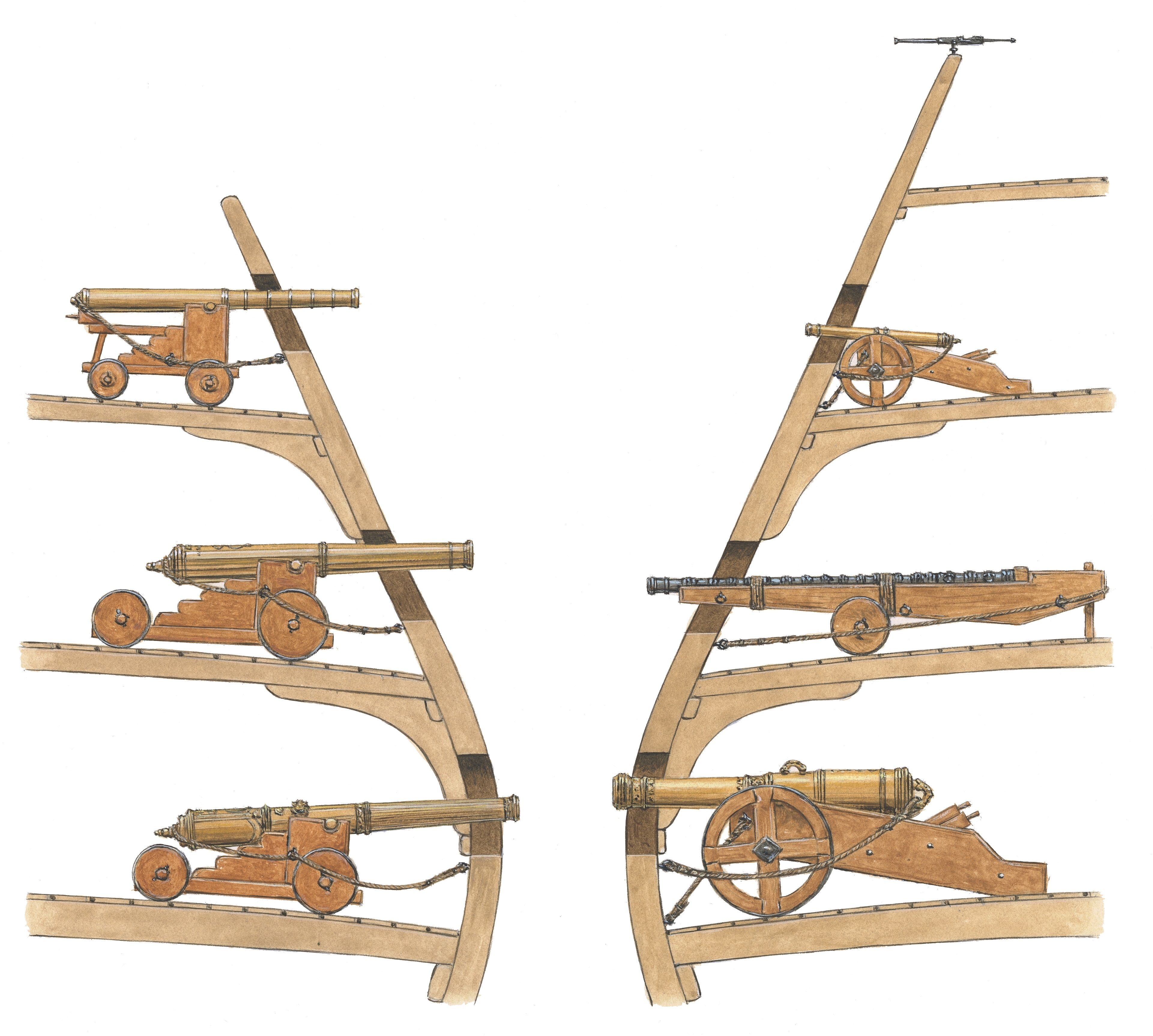

Galleon gun decks (English left, Spanish right).

(Artwork by Adam Hook)

Galleons came from that thinking. The lower deck was raised, placing it high enough above the waterline so gunports cut into it would not admit water under normal circumstances. That raised the depth of the hold, making it a more efficient cargo carrier. The length to breadth ratio increased from the 2:1 or 2.5:1 of the carrack to 3:1 to 3.3:1. This slimmer design proved a faster sailer, and a generally more seaworthy ship.

This new class of warship was called a galleon, a name most probably derived from the Portuguese galeão (or war ship). Galleons were warships, the first ship designed to specifically carry cannon. The galleon also had a built-up beakhead, and prominent stern and forecastles. It could also have more than two full decks (decks run the length of a ship, as opposed to platforms spanning part of the length). Bigger galleons, including the monster Spanish ones built after the Armada, often had two full gundecks.

Galleons first emerged in Italy during the late 1400s. The Portuguese soon adopted the design in the early 1500s, and the Spanish copied them between 1517 and 1530. The English began building galleons in 1545.

Each nation had a preferred size for galleons. The English preferred smaller galleons with few but heavy guns. The Iberians preferred large galleons with many light cannon. England was then the world’s leader in gunfounding, but too poor to afford (or need) large ships. Spain lagged in metal working (many of their cannon were smuggled in from England) but needed and could afford large ships to service their New World colonies.

The White Bear, an Elizabethan galleon.

(Author's collection)

Most galleons built between 1500 and 1590 were built by private consortiums for commercial use rather than for national navies. Galleons were first-rate cargo haulers, faster than carracks, and better able to defend themselves in the lawless seas of the times. Keeping large numbers of national warships idle during peacetime was expensive. Instead, when a nation went to war it used merchant shipping. National governments encouraged construction of galleons due to their ability to serve as warships.

The galleon dominated the seas from 1550 through 1600. Then new types of warships replaced it. Sloops-of-war, two-deckers, and ships-of-the-line emerged in the 1600s, with the frigate (most similar in role to the galleon) appearing in the middle of the 1700s. The name – and romance – lived on, however. The annual ships carrying silver and precious cargoes between Manila and Acapulco continued to be called galleons, as did the warships (typically frigates) returning Spain’s New World silver to their home country.

Spanish Galleon vs English Galleon publishes 26 November. Preorder your copy now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment