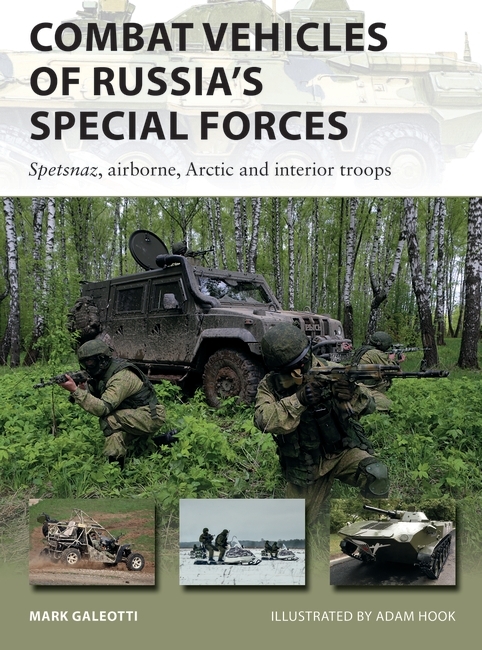

On the blog today, Mark Galeotti looks at how the Syrian War has been both a shop window and testing ground for many of the several of the specialized vehicles used by the Russian military, the subject of his latest title Combat Vehicles of Russia’s Special Forces.

Amidst the miseries and inhumanities of the Syrian Civil War, there is one inescapable and rather uncomfortable truth: this has, so far at least, been a very good war for the Russian military. The five years since they first intervened there have given Moscow an opportunity to ‘blood’ a whole generation of officers, especially in the air forces. It has provided them the opportunity to show off new capabilities and weapons systems, from the Ka-52 ‘Alligator’ helicopter gunship to the Kalibr cruise missiles periodically launched against Islamic State targets, not least as a shop window to prospective buyers. (Since then, for example, the United Arab Emirates began negotiations to buy Sukhoi Su-32 fighter bombers, in part thanks to their showing there.)

As Russian President Vladimir Putin said, “the use of our armed forces in combat conditions is a unique experience and a unique tool to improve our armed forces… No exercises can compare with actually using the armed forces in combat conditions.” Syria has also become a testing ground for weapons and vehicles being considered or prepared for service. Some of these are destined to be mainstays of front-line combat formations like the T-14 Armata tank and Su-57 ‘Felon’ stealth fighter.

Terminator in Syria

Others are the more specialized vehicles of the sort covered in my New Vanguard title, Combat Vehicles of Russia’s Special Forces, out this month. Sometimes, this is simply a convenient opportunity to deploy vehicles anyway in use. In 2017, for example, a single example of the new BMPT-72 Terminator-2 was deployed to Syria for field trials. This was a product of the urban warfare experiences of the two Chechen wars, where it became painfully clear that regular tanks without support could be destroyed or disabled by a handful of men with rocket launchers, and that mechanized infantry in thinner-skinned APCs were often vulnerable in the close environment of the city.

At first, the Russians experimented with the BTR-T, a dated T-55 tank hull converted into a heavily armoured personnel carrier. This ended up as the worst of all worlds, an expensive and clumsy infantry fighting vehicle able to carry just five soldiers in extraordinarily uncomfortable conditions. It never got beyond proof-of-concept designs. Instead, the Russians opted for the BMPT, the Tank Support Combat Vehicle. Based on a more modern T-72 hull, this beast mounts an extravagant array of weapons: four laser-guided 9M120 Ataka (AT-9 Spiral-2) missile launchers, two 30mm 2A42 autocannons, a 7.62 mm PKTM machine gun, and two AG-17D or AGS-30 automatic grenade launchers. With five crew, each with their own sighting systems, including day/night capabilities, four different targets can, in theory, be engaged at once, and the autocannon and grenade launchers are optimized for urban operations, including the capacity to be elevated to rake the tops of buildings.

In 2013, the Russians unveiled an export version, the BMPT-72 Terminator 2, as a retrofit option for existing T-72s, that omits the grenade launchers and thus brings the crew down to three. In 2017, a single BMPT-72 was shipped to Syria for live field testing. Formally assigned to the Syrian Republican Guard, it was actually crewed by Russians and surrounded by a team of Russian technicians and security personnel. The Terminator saw operation in several theatres, and seems to have been going through field modification in the process, acquiring additional second-generation Relikt reactive armour before operations in the Homs governorate.

Jeeps by other name

This has very much been a war for the Light Multi-Role Vehicle (why can’t we just say ‘jeep’ anymore?), and alongside their standard GAZ Tigr (Tiger) 4x4, a lightly-armoured but rugged design in service since 2006, the Russians fielded the Italian-made IVECO M65 Lince (Lynx). Originally ordered in 2011, it soon fell foul of political ‘buy Russian’ pressures, and when then-defence minister Anatoly Serdyukov was sacked in 2012, his successor Sergei Shoigu blocked further orders. Nonetheless, while smaller than the Tigr, the M65 offers great survivability, and in Syria has been widely used by the Russian Military Police, who are patrolling the often-broken ceasefire lines.

However, the Russians are also having to adapt to an environment in which they are not used to fight, and rebels with their own styles of combat. Facing rebels prone to use converted all-terrain ‘technicals’, for example, in 2016 the Russians supplied the Syrian Arab Army with a number of UAZ Patriot pick-up trucks armed with 12.7mm Kord heavy machine guns and AGS-17 grenade launchers. Their role was to be highly mobile convoy escorts and ‘counter-technicals’.

The experience seems to have sparked wider interest in such vehicles. In 2017, it was announced that one of the Russian 30th Motor-Rifle Brigade’s four battalions would be converted into a light motorized unit. It is being equipped with UAZ Patriots, some carrying seven soldiers and a machine gun, others gun-trucks mounting an autocannon or 82mm mortars. The 30th Brigade is based at Samara in central Russia, not so much desert territory, but steppes, forests and mountains. Given that the UAZ Patriot can reach speeds of 150kph and is much more fuel efficient than heavier, armoured APCs, the idea appears to be to test the notion that such a force could provide highly mobile raid and reaction forces in a range of difficult environments, from deserts to woodland, where the larger BTR-80s of the rest of the brigade will have trouble or be forced to move more slowly.

An even smaller and nippier vehicle seen trialled in Syria is the Chaborz M-3, a three-seat militarized off-road buggy. Built in Chechnya, this can achieve 130kph and mounts an automatic grenade launcher and a 7.62mm PKT machine gun, although by all accounts firing grenades while moving at speed on uneven terrain risks flipping the vehicle: proof that more firepower is not always better.

Robotank in the sand

Perhaps the most unusual piece of kit being put through its paces in Syria was the Uran-9, a tracked unmanned combat ground vehicle – in other words, a drone mini-tank. Some 5m long and 2.5m tall and wide, it nonetheless packs a 2A72 30mm autocannon, a 7.62mm PKTM machine gun, and two extendable firing arms mounting 4 9M120 Ataka anti-tank or 9K333 Verba anti-air missiles, as and up to twelve Shmel-M short-range thermobaric rockets.

The idea is that it can be deployed to soften up enemy defences before an attack, or to provide mobile perimeter security, patrolling on autopilot until something alerts it and a human operator takes over operation. That said, although manufacturers, JSC 766 UPTK (part of the Kalashnikov Group) predictably talked up its performance in Syria, most assessments are that it was something of a disappointment. The main gun often operated with a delay, and its sensors could only acquire targets less than half as far away as expected. Most dramatically, the remote-control system proved much more erratic and short-range than expected. High buildings had an especially bad effect on transmissions – a problem for a vehicle designed for urban combat – and a couple of times the command station actually lost control of Uran-9s for up to 90 minutes.

This was hardly an impressive debut, although JSC 766 UPTK claim that these are just software rather than fundamental design issues, and the Russian defence ministry does seem enthusiastic about a new generation of drones and robots in the sky, in and under the sea, and on the ground.

But the fundamental point is that it didn’t really matter too much how well the Uran-9 worked in Syria, or any of the systems used there. What matters are the lessons learned that can be transferred to other theatres. The military high command wants this war to be a one-off deployment, not a lasting distraction from their main missions, the defence of the Motherland and projection of Russian power in its immediate neighbourhood.

As one General Staff officer put it to me, ‘every ruble spent on desert kit will be welcome today, but useless in a few years’ time.’ This may well be over-optimistic: the Americans and the British could tell them that deployments into the Middle East are easier to start than to control or to end. For the moment, though, Moscow still believes that Syria is a perfect theatre to test and show off its new systems, with little real risk to its greater interest or missions.

Combat Vehicles of Russia’s Special Forces publishes 28 May. Preorder your copy from the website now.

On the blog today, Mark Galeotti looks at how the Syrian War has been both a shop window and testing ground for many of the several of the specialized vehicles used by the Russian military, the subject of his latest title Combat Vehicles of Russia’s Special Forces.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment