David Smith, author of The First Anglo-Sikh War 1845–46, gives us an insight into the inspiration behind his title and how the book came about.

A work of fiction is an unusual place for an Osprey Campaign title to start, but Flashman and the Mountain of Light, by George MacDonald Fraser, could be considered the genesis of my new book, The First Anglo-Sikh War 1845–46.

It must be nearly 20 years ago that I read of Harry Flashman’s misadventures in the Punjab court as war brewed between the Sikh Empire and the East India Company. Something must have stuck in my mind (not surprising, considering the brilliance of Fraser’s writing), because when the chance came to write a Campaign title on the war, I jumped at it.

Fraser had a few advantages over me. Not only could he choose a snappier title for his book, he could also fill in any gaps in his research with conjecture. This is not an option for a historian, and it meant that some of the most colourful events in his novel could not find their way into my book, because I could find no evidence of them ever happening. Despite this, Fraser’s genius at working fictional details into facts has never been better demonstrated than when he made Flashman himself the architect of the Sikh Army’s downfall.

Flashman, for those who have never read Fraser’s books, is just about the most cowardly figure in the history of fiction. By repeated strokes of fortune, however, he emerges from every episode of his life covered in glory and hailed as a hero. Fraser placed Flashman at the heart of some of the greatest military events of the 19th century – the Charge of the Light Brigade, the Retreat from Kabul, even the Battle of the Little Big Horn – and he was front and centre in the desperately close battles of the First Anglo-Sikh War.

Given Flashman’s ability to create havoc wherever he went, this conflict was a gift for Fraser. The war turned on the treachery of the Sikh generals, Lal and Tej Singh, who actively undermined their armies, split their forces, moved too slowly to catch the unprepared British off their guard and refused to attack when victory awaited them. In reality, this was the result of intrigue and machinations at the Punjab court, and growing fears over the strength of their own army among the Sikh aristocracy. In Fraser’s hands, it was down to some nifty negotiations carried out by Flashman himself.

Fraser’s battle descriptions are superb, and it is more than a little disappointing to know that my work cannot hope to match the eloquence of his simple description of the Battle of Ferozeshah, witnessed by Flashman from a safe distance:

‘My memories of that night are a mixture of confused pictures: Ferozeshah, two miles away, like a vision of hell, a sea of flames under red clouds with explosions everywhere; men lurching out of the dark, carrying wounded comrades; the long dark mass of our bivouacs on the open ground, and the unceasing screams and groans of the wounded all night long; bloody hands thrusting bloody papers before me under the storm-lantern—Littler had lost 185 men in only ten minutes, I remember.’

My research for the book confirmed that the nightmarish picture Fraser had painted was an accurate one. This was a particularly hard-fought campaign, and one that would have been so much harder for the British had the Sikhs been properly led. Highly disciplined and trained along European lines, they were more than a match for the exhausted army thrown against them by Sir Hugh Gough. In only one encounter during the entire war did the British face an opponent that was not hamstrung by its own leadership – at Aliwal, Sir Harry Smith won a near-perfect battle against a Sikh force led by a man who was no traitor, but sadly no general either.

Despite the wealth of primary sources, however, it is not easy to get a clear picture of what actually happened on the dust-choked battlefields south of the Sutlej river. Battles are chaotic affairs and even eye-witness accounts can vary dramatically in their details. In the final battle of the war, for instance, at Sobraon, did the 10th Foot advance doggedly into a fierce artillery barrage, or did they walk unopposed through the Sikh lines with muskets shouldered? There are first-hand accounts of the battle championing both versions of events.

The fact is that for the men on the ground, in the thick of the fighting, it becomes impossible to discern anything that is happening more than a few yards away. Flashman, in his inimitable style, summed it up neatly when he declared: ‘The best way to view a clash of armies is from a hot-air balloon, for not only can you see what’s doing, you’re safely out of the line of fire.’

Putting together a coherent battle narrative is therefore a tricky task, made more difficult the more material you have to work with. I envy the freedom of a fiction writer, but at the same time there is great satisfaction in weighing up evidence and choosing the most plausible sequence of events. It might mean you have to leave out some juicy details that cannot be backed up by evidence, but if the final result is a compelling narrative nonetheless, a historian can be happy.

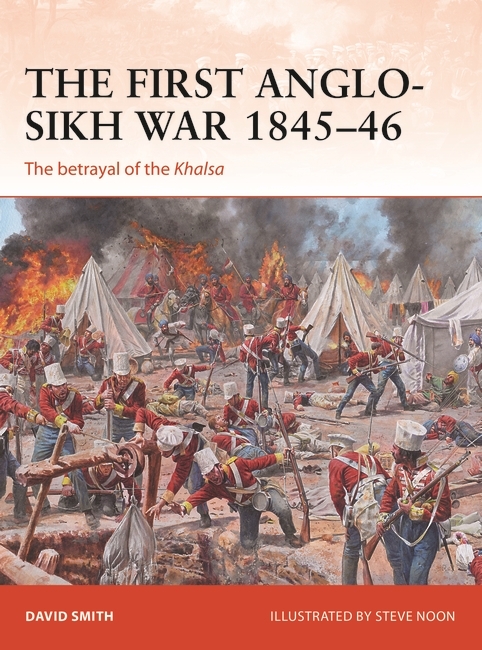

And there is one element of my book that is every bit as colourful and dramatic as even the best passages from the adventures of Harry Flashman, although, sadly, I can claim none of the credit for it. The battle scenes, created by Steve Noon, are simply the best I have ever seen in an Osprey book. When I consider the laughably amateur sketches I provided him to work with, the stunningly vivid pictures he created are even more impressive.

The First Anglo-Sikh War 1845–46 publishes today. Get your copy here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment