In today's blog post, Murray Dahm, author of Macedonian Phalangite vs Persian Warrior, gives an intriguing overview of Alexander the Great's Macedonian army.

The accomplishments of Alexander the Great and his army of Macedonians are ingrained in the memory of the annals of military accomplishments and history in general. The world as we know it was shaped by Alexander’s achievements. And yet his accomplishments remain in many ways unbelievable. Alexander invaded the Achaemenid Persian empire in 334 BC at the head of an army of perhaps 40,000 men in total. He was only twenty-two. At the core of Alexander’s army was the phalanx: 9,000 hardy men drawn from Macedon’s mountainous terrain and divided into six battalions (each a taxis; plural taxeis) of 1,500 men. Each taxis was drawn from a particular region of Macedonia and its officers were from the nobility of that same area. These veteran phalangites had served Alexander’s father Philip and Alexander himself in Greece and Thrace, and they bore the brunt of Alexander’s conquests. They were not the most glamorous elements of Alexander’s army (that role would fall to the cavalry) but they were its most essential. The phalanx would remain undefeated in a decade of almost continuous warfare. The empire that they would conquer was one of the largest the ancient world ever saw; larger even than Rome’s empire at its height.

The Achaemenid empire stretched from modern Turkey to India and from Egypt to the Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea. The military system which had brought that empire into being in the 6th century BC was still intact and relatively unchallenged when Alexander launched his invasion. The Persian armies which had conquered that empire still controlled it and had no reason to think they would not continue to do so. Persian armies were massive, drawn from the territories all over the empire and each culture fought in its own style. At the core of the Persian army, however, were infantry and cavalry battalions levied from the Persian and Median homelands. Wherever members of the Persian nobility held office within the empire, a number of these troops would accompany them. And whenever the Great King took the field, the Persian and Median infantry would take pride of place, especially his bodyguard of 10,000 Immortals (Persian infantry drawn from the best of the levied troops) – and called immortal because their number could always be maintained from the levied troops.

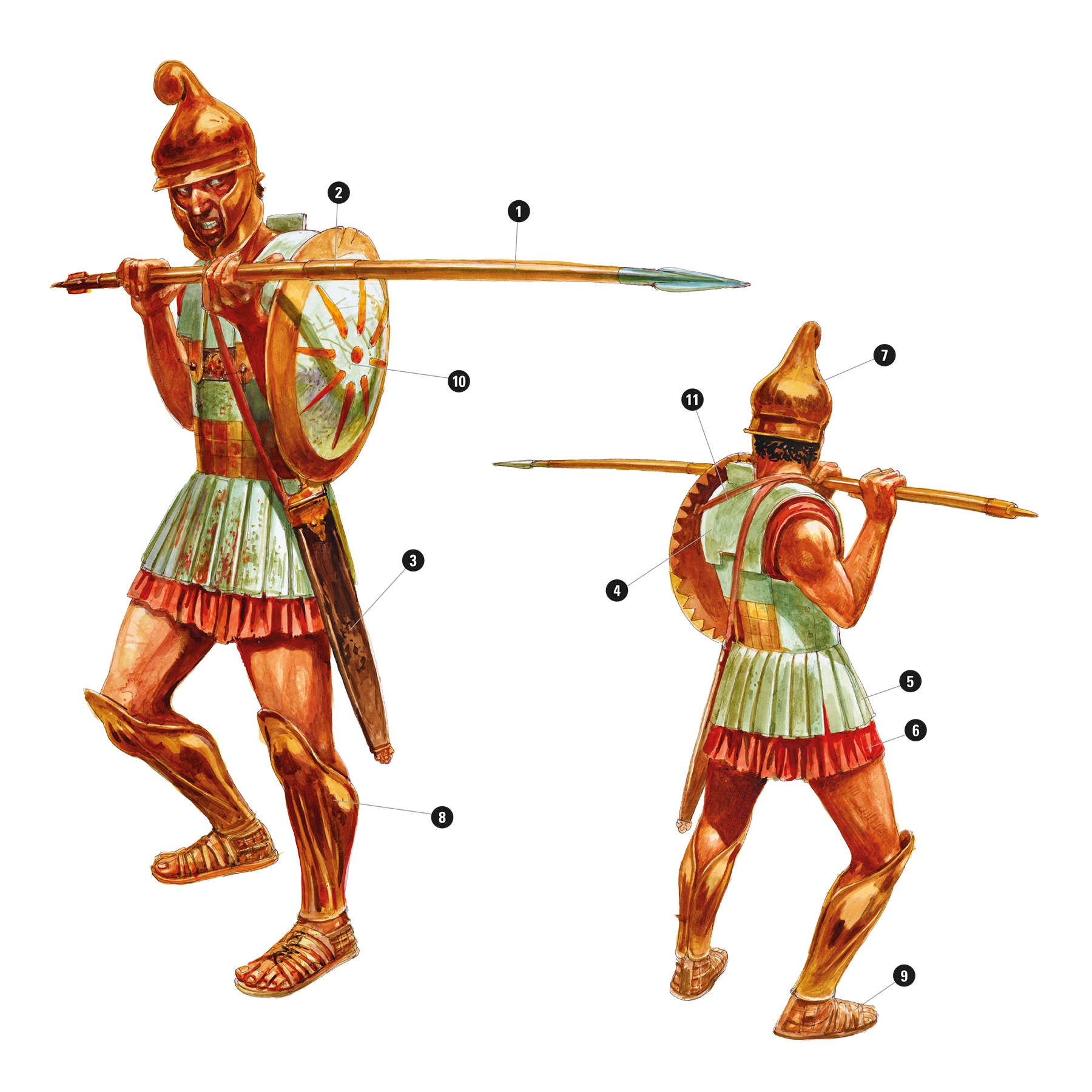

The Macedonian phalangite was armed primarily with a long, two-handed pike: the sarissa, 5.5 metres long (made mostly from cornel wood and transported in halves which were joined together before battle). The formation of the phalanx on the battlefield literally bristled with spearpoints. The usual depth of the phalanx was sixteen men – five shafts would extend beyond the front line and the remainder would be held aloft at an angle to break up enemy missile fire. The phalangite also wore a shield on their left forearm, wore linen armour and carried a sword as a secondary weapon. The army they faced outnumbered them immensely. We are told unbelievable numbers, into the hundreds of thousands, of the men in Persian armies facing the Macedonians. Often the Persian contingent alone outnumbered the entire Macedonian army but these successive armies were faced and defeated by Alexander’s small army of professionals. The primary weapon of the Persian infantry was archery – we have depictions of Persian infantry armed with bows and spears and we know that units were known as spear-bearers. It is probable that behind a shield bearer a certain number of archers took station (up to ten deep).

Artwork by Peter Dennis

In the battles where Alexander faced the Persian army on the open field – the Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela (all of which I examine) – we can see exactly how Alexander managed to defeat such large armies and such a huge empire. Central to that success was Alexander’s use of the phalanx and his combination of it with his use of cavalry tactics – the Companions were the elite noble cavalry of Macedonia, with Alexander leading them from the front. In each battle, Alexander used the strengths of the phalanx,which was both a strong bulwark of defence and a spear-bristling offensive threat. At the same time, the Persians who faced Alexander – the Persian commanders at the Granicus and the Great King Darius III himself at Issus and Gaugamela – used the Persian army as they always had. They expected that the sheer numbers of Persian troops arrayed and the ineffable number of arrows they could shoot, would deter or defeat any enemy. And yet the Persians now faced an uncowed enemy – outnumbered Macedonians who advanced towards them without hesitation. What is more, as the Macedonians headed into the Persian interior, they moved further and further away from home and any Macedonian defeat would have spelled disaster and the end of their enterprise. Also, it should be remembered that Alexander fought at the head of his army and risked death in every skirmish; if he fell then the inexorable Macedonian onslaught would grind to a halt.

Much has been written on Alexander the Great and yet many questions remain unanswered or disputed. We have several primary sources which survive and they are usually divided into trustworthy and less (or un-) trustworthy. Every one of our sources offers unique (and reliable) insights, however, and rejecting one in favour of the others usually creates more problems than it solves. We must also bear in mind that ancient authors were not writing what we would want them to write about. Often, those authors had other agenda, especially in regard to Alexander – a key figure for writers concerned with philosophy, theories about kingship, morals, humanism, as well as military brilliance. Exploring these primary sources with fresh eyes, however, allows us to make several new observations about Alexander’s army, his use of the phalanx, and even how he planned and conducted his campaigns and fought in his battles. Those battles have been explored and pored over for more than two millennia and yet there are still new insights to be found and new things to be said about them.

To read more, pre-order your copy of Macedonian Phalangite vs Persian Warrior.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment