This June sees the publication of Mark Lardas's US Flush-Deck Destroyers 1916–45. Today on the blog, Mark joins us to discuss the life of some of these destroyers following their wartime service.

Every warship class reaches the end of its life. In a lucky few, a specimen gets preserved as a museum ship. Examples include the World War II Town-class, with the cruiser Belfast, or the more humble Edsall-class destroyer escort, represented by USS Stewart in Galveston’s Seawolf Park. Most end with every ship going to the scrappers, even the most distinguished classes of warships.

The last surviving ship in a class often has an eccentric story. The last surviving US flush-deck destroyer is one example. It started out as USS Putnam (DD-287), but it spent the last two-thirds of its life as MS Teapa, a fast fruit boat.

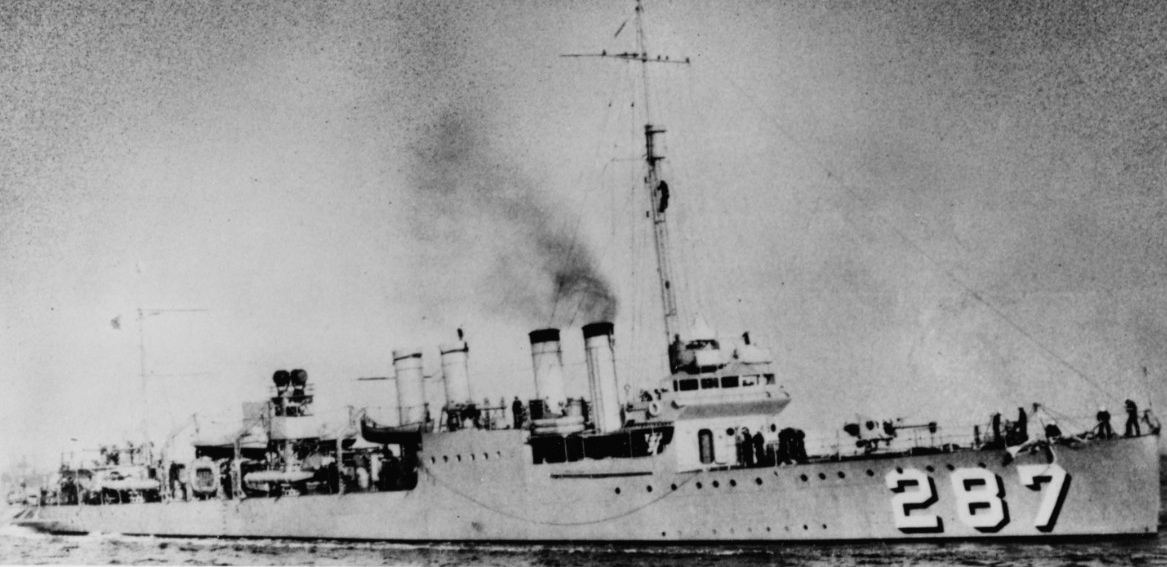

USS Putnam (DD-287) during its salad days as a United States Navy destroyer

USS Putnam (DD-287) during its salad days as a United States Navy destroyer

Converting a destroyer to a fruit boat is not quite as bananas as it sounds. Destroyers are shallow-draft, allowing them to steam up rivers to banana plantations and load directly from the source. That saves transportation costs associated with sending bananas by rail to port.

A destroyer mainly consists of propulsion plant and weapons, but three-quarters of its power is required to squeeze out the last few knots of speed. It can cruise at half-speed quite comfortably on just one boiler. Remove the extra boilers and engine, and you have a fast vessel with a comfortable amount of storage space. You can even replace the steam plant with diesels, simplifying the engineering. An ex-destroyer moved fast enough that you did not need to refrigerate the bananas. Air scoops forcing fresh air over the fruit sufficed to keep it fresh.

(Shallow draft and high speed was one reason so many flush-deck destroyers were converted to troop transports in World War II. I suspect the Marines and soldiers crammed into these felt a kinship with the bananas carried in the fruit boats.)

Snyder Banana Company was the first to use destroyers as fruit boats. In 1920 it purchased three pre-World War I Truxtun-class destroyers, and converted them into banana carriers. The experiment proved successful. In 1930 the London Naval Limitations Treaty forced the US Navy to scrap 35 flush-deck destroyers. The Standard Fruit Company of New Orleans bought four of these destroyers marked for disposal: Putnam (DD-287), Worden (DD-288), Dale (DD-290), and Osborne (DD-295).

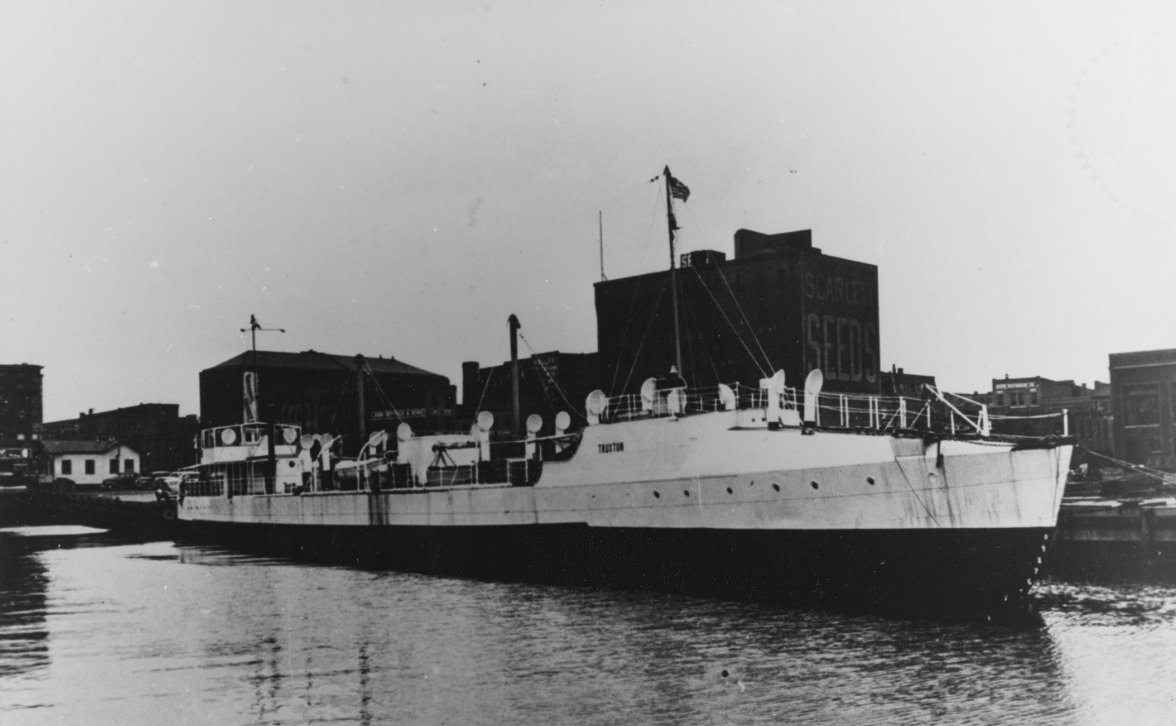

SS Truxton - the former USS Truxton (DD-14) after conversion to a banana boat

SS Truxton - the former USS Truxton (DD-14) after conversion to a banana boat

All four had the wretched Yarrow boilers that wore out quickly, but that did not matter. The four destroyers were gutted, with the steam engines and boilers replaced by two 750hp diesel engines. With the two engines running flat out, their 1,500hp could drive the ships at 16 knots. As rebuilt, the ships could be loaded with 25,000 stems of bananas, or roughly 750 to 1,200 tons. A new superstructure was added, as were lots of air scoops, to ventilate the bananas in transit.

The rebuilt vessels were renamed (respectively) Teapa, Tabasco, Masaya, and Matagalpa. They entered service in 1931, running fruit between Central America and New Orleans. Tabasco ran aground in 1933 off the Yucatan Peninsula and was wrecked. The other three continued running fruit through the 1930s up until the United States entered World War II.

MS Teapa after World War II

MS Teapa after World War II

In early 1942, with the Philippines under siege by Japan, Douglas McArthur was calling for blockade runners to bring vitally-needed supplies to the beleaguered defenders. Someone remembered the ex-destroyers (perhaps because they were featured in a June 1940 Our Navy article), and decided these fast transports would make first-rate blockade runners. The Army chartered the three vessels, armed them, loaded them up with supplies, and started them to the Philippines.

Well, sort of.

Masaya left New Orleans for Corregidor on March 3, 1942, carrying ammunition, medical supplies, aviation gasoline, and mail for the garrison. Matagalpa followed with small arms, mortars, serum and (probably considered most vital in 1942) cigarettes. By the time both ships reached Pearl Harbor, Corregidor had fallen. Teapa, tail-end-Charlie, had only reached San Francisco.

Masaya and Matagalpa were redirected to Australia, where they served McArthur as transports in the Southwest Pacific Area. Neither ship lasted long. Matagalpa caught fire at dock, shortly after arriving at Sydney, Australia in June 1942. Gutted by fire, she was scrapped. Masaya ran supplies between Australia and New Guinea for nearly a year. Japanese dive-bombers caught her at Oro Bay (off New Guinea’s northeast coast, near Buna) on March 28, 1943 and sank her.

Teapa was sent to the Aleutians, running supplies between Stewart, Alaska and Seattle, Washington. At least that was the plan. Shortly after arriving at Stewart for the first time, it too caught fire. A survey after the fire revealed the ship’s decks and wiring to be badly damaged. After unloading any supplies worth salvaging, Teapa returned to Seattle, where it remained for the rest of the war, serving as a training ship.

Disarmed and demobilized when the war ended, Teapa returned to the fruit trade. This time it was purchased by McCormick Shipping Corporation. From 1947 through 1950 it ran bananas between Central America and the United States. It was laid up in 1950.

By 1950, the United States and Great Britain had scrapped all the surviving flush-deck destroyers that either nation had. The Soviet Union had been lent nine during the war. One was sunk during the war, with six others returned by 1950. The Soviets were tardy about returning the remaining two. They had been stripped of parts to keep the other destroyers running, and were immobile. In 1952 the Soviets permitted Britain to send tugs to tow the ships back to Britain. Upon arrival they were promptly scrapped.

That left Teapa the sole surviving flush-deck destroyer. Why McCormick Shipping kept the ship is a mystery. It was out of date, uneconomical to run, and an expense to keep. Corporate inertia is probably the best explanation. In 1955 McCormick finally sold the hulk to a Miami-based scrap metal company. By year’s end the last flush-deck destroyer was gone.

To read about the military career of SS Truxton and USS Putnam, as well as other US Flush-Deck Destroyers during and between World War I and World War II, pre-order your copy of New Vanguard 259 by clicking here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment