Today on the blog we welcome back Mark Lardas, who discusses his latest book CAM 314: Nashville 1864, and dispels popular misconceptions about its link to the March to the Sea.

Why a Campaign on Nashville? Wasn’t that part of the March to the Sea? It is a question which appeared when Osprey announced the book. That question was actually one of the reasons I wanted to write a Campaign about Nashville. Despite a popular misconception, Nashville really was independent of the March to the Sea.

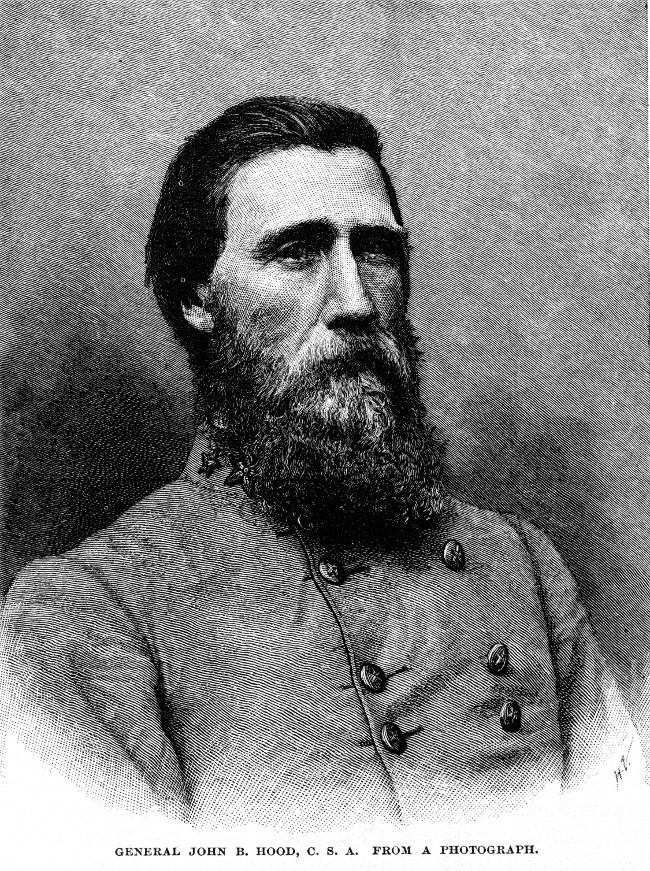

It was fought at the same time as the March to the Sea, and many troops involved in both campaigns had fought in the Atlanta campaign which led up to both Nashville and the March to the Sea. The Confederate commander during the Nashville campaign, John Bell Hood, wanted them to be linked. He believed his invasion of Tennessee would force Sherman to abandon Atlanta and abandon any movement deeper into Georgia. It is easy to see why folks today believe the two are linked.

It was fought at the same time as the March to the Sea, and many troops involved in both campaigns had fought in the Atlanta campaign which led up to both Nashville and the March to the Sea. The Confederate commander during the Nashville campaign, John Bell Hood, wanted them to be linked. He believed his invasion of Tennessee would force Sherman to abandon Atlanta and abandon any movement deeper into Georgia. It is easy to see why folks today believe the two are linked.

Yet they are not. Sherman made that decision when he decided to ignore Hood. Instead, he took what he believed were his best troops and marched south. Sherman gave the rest of his army to George Thomas, and dumped the problem of dealing with Hood into Thomas’s hands. Sherman then marched out of the picture and on to glory and Savannah.

Fortunately Thomas’s hands were capable ones. Thomas was left with a rag-tag collection of disparate troops. They included garrison troops, invalids from the Atlanta campaign, mostly-dismounted cavalry (Sherman took all the best horses), and Sherman’s problem children. Chief problem child was John McAllister Schofield, one of the most difficult subordinate generals any commander could inherit. Schofield was a competent battlefield commander, but his true talents lay in army politicking. He spent more time sniping at Thomas, in an effort to replace him, than he did fighting the Confederate invaders.

The Southern command included two of the Confederacy’s most fascinating  commanders: John Bell Hood, and Nathan Bedford Forrest. Hood resembled the Black Knight from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. He scattered bits and pieces of himself over several battlefields. By 1864 Hood had literally contributed an arm and a leg to the Confederate cause. Yet he was as pugnacious as ever, always seeking an opportunity to attack.

commanders: John Bell Hood, and Nathan Bedford Forrest. Hood resembled the Black Knight from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. He scattered bits and pieces of himself over several battlefields. By 1864 Hood had literally contributed an arm and a leg to the Confederate cause. Yet he was as pugnacious as ever, always seeking an opportunity to attack.

Bedford Forrest was equally pugnacious, but more measured in aggressiveness. A self-taught strategist, Forrest was possibly the best cavalry commander of the war. He never fought a stand-up frontal assault when a flank attack yielded better results. Forrest wanted to win – not prove his bravery.

Hood’s 1864 invasion of Central Tennessee was the result of Hood’s need to attack and always attack. His Army of Tennessee was too weak to attack Sherman’s forces in Atlanta and Hood did not want to stand on the defensive. So Hood convinced Jefferson Davis to allow the Army of Tennessee to attack elsewhere. Central Tennessee was far enough from Sherman’s Atlanta base that Hood could attack there.

Hood’s plan was based on several misconceptions. He assumed Sherman would react by chasing after the Army of Tennessee. Instead Sherman completely ignored Hood. Hood also assumed Confederate sympathizers in Tennessee (and possibly even Kentucky) would flock to his army as he advanced, strengthening the Army of Tennessee. By 1864 every male in those states willing to fight for the Confederacy had already joined up. The only folks remaining were pro-Union or those who simply wished to be left alone. Finally, Hood assumed Confederate courage could substitute for logistics. His army lacked both supplies and the train to move supplies.

Davis was aware of these problems. He approved Hood’s plan for one simple reason: it was a plan, and no other plan was offered. Despite the long odds against the Confederates, Hood’s invasion of Central Tennessee offer perhaps the last opportunity for the South to win the Civil War, especially after Lincoln’s reelection.

Hood’s principal opponent, George Thomas, was as fascinating as Hood. A Virginian, he stayed loyal to the Union. He was possibly the most underrated Union commander of the Civil War. A quiet man, he had two outstanding talents: He was a tenacious defender and a powerful attacker. He saved the Union Army at Chickamauga and Chattanooga in 1863. His attack in the center of the Confederate line on Missionary Ridge shattered the Army of Tennessee on the third day at Chattanooga.

US gunboat General Grant, one of the many vessels carrying supplies and providing firepower on the Tennessee River

Thomas was never held in high favor by Grant. Thomas was methodical and deliberate, too methodical and deliberate for Grant’s taste. Yet when Thomas did strike it was always with the effect of a sledgehammer striking a lathe screen.

Although Thomas’s forces outnumbered Hood’s army, Thomas had his army scattered from the Cumberland to the Tennessee Rivers. One of his corps was not yet in the theater when the campaign started, as it was en route on the Cumberland River. Thomas also had the challenge of facing Hood while simultaneously holding Nashville and Chattanooga, Tennessee.

I first became aware of the Nashville campaign while writing Warrior 114: African American Soldier in the Civil War. (Black troops played a significant part in the Union victory at Nashville and in the various holding actions which led up to that battle.) The more I read about this campaign, the more convinced I became that this was one of the most neglected and ignored campaigns of the American Civil War. It was the Confederacy’s last chance – and the campaign where a neglected American hero, George Thomas, managed something Grant never achieved: destroying a Confederate army in the field.

Read the book, and tell me whether or not you agree with my assessment.

Mark's new book Nashville 1864 is now available to preorder from our website, you can do so by clicking here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment