With the publication of The Locomotive of War by Bloomsbury, author Peter Clarke reveals how money, empire, power and guilt played a monumental part in the British involvement of World War I, and how each are a key theme in his latest book.

One of the most famous British images of the First World War is surely the poster featuring the face of Field Marshal Lord Kitchener. His face stares out at us; his finger points straight towards us; his message is simple: "Your Country Needs You." I reproduce this in The Locomotive of War as literally the face of British recruitment in the crisis of an unanticipated war. In 1913 the total British armed forces had numbered only 400,000. During 1914 this figure immediately doubled and reached nearly 2.5 million by the end of 1915 – the largest volunteer army raised in any country in recorded history.

But this was not all – far from it. Let me suggest why I subtitle my book: money, empire, power and guilt.

One reason is that the whole of the British Empire was carried into war by the British decision: the colonies under direct rule and also the Indian Raj which possessed the only large standing army available to Britain at the time. More than this, the self-governing Dominions followed Britain, even South Africa with its large population of Dutch descent. In anglophone Canada and Newfoundland – less so in francophone Quebec – the war was a popular cause, as the amazing flow of volunteers showed. The same was true in Australia and New Zealand.

During the war, the Dominions were to enlist 1.3 million soldiers, of whom a million served overseas, mainly on the western front. Of these, 144,000 were killed, with a slightly higher casualty rate than British troops. This was not a token commitment. Canada, with a population of 8 million, sent 458,000 troops abroad, some of them recruited from Newfoundland, which additionally sent over 9000. Australia and New Zealand, with a combined population of just over 6 million, sent 444,000. South Africa, with a white population of 1.4 million, had 136,000 troops serving, 50,000 of them in German South West Africa; and 44,000 black South Africans also served in labour brigades in France. The Indian Army recruited 827,000 combatants and 446,000 non-combatants.

Indian Cavalry on the Western Front

Indian Cavalry on the Western Front

This was indeed a war that was worldwide in its scope – became a world war because of the Empire and its interaction with power politics. The Royal Navy guaranteed the integrity of imperial communications, its priority to keep the sea lanes open. This is why it had been built up to its current strength in matching the German challenge. Moreover, it was because of that challenge, notionally requiring the Royal Navy to sustain its sixty-per-cent superiority in the North Sea, that the British fleet had been concentrated there, with the concurrent redeployment of the French fleet to the Mediterranean. The consequent exposure of the French coasts, generating a moral obligation for the Royal Navy to protect them, was a further logical consequence.

Britain initially sought to wage war on the same liberal assumptions that had served it well in the long years of European peace. This is where money comes in. In retrospect this often seemed like a golden age - literally so since an international division of labour based upon free trade and the gold standard seemed to guarantee a gracious, spacious way of life for the possessing classes. Such was the garden party that was suddenly disturbed in the summer of 1914 by an international crisis that rocketed out of control. And in the ensuing conflict the old assumptions were challenged. The gold standard was maintained in a nominal way, but with huge subsequent costs through the international debts that were run up. And Britain's heroic recruiting efforts were superseded by a resort to conscription.

This was a war, then, in which money, empire and power were obviously big factors. But so was guilt. For the reason that a Liberal Government took Britain into the war in August 1914 turned on a moral issue: whether to defend the integrity of neutral Belgium, as protected by international treaty. True, Austria was already at war in the Balkans, where the trouble had begun; true, Germany was offering Austria its support as an ally; true, Russia was intervening on the other side – and bringing in France as its own ally.

But what touched a nerve in the Liberal cabinet – and among its liberal supporters across Britain – was the violation of Belgian neutrality. In this situation, the resonance of the example of their great hero Gladstone touched the liberal conscience. From beyond the grave, Gladstone's politics of morality and emotion, intent on holding the guilty to account, suddenly transformed the situation in Liberal eyes. Here was the lens through which they viewed the decision to declare war on Germany.

And if Germany was thus the guilty party, should it not be held responsible for the consequences? The peacemaking at the end of the war, resulting in the Treaty of Versailles, has usually been explained as an outburst of vengeful nationalism, in France and Britain alike, with the Americans unable to restrain it. But maybe we need to understand the Anglo-American viewpoint in a different sense – as an expression of a common tradition of liberal moralism which naturally looked for a guilty party in international affairs as much as in any other context.

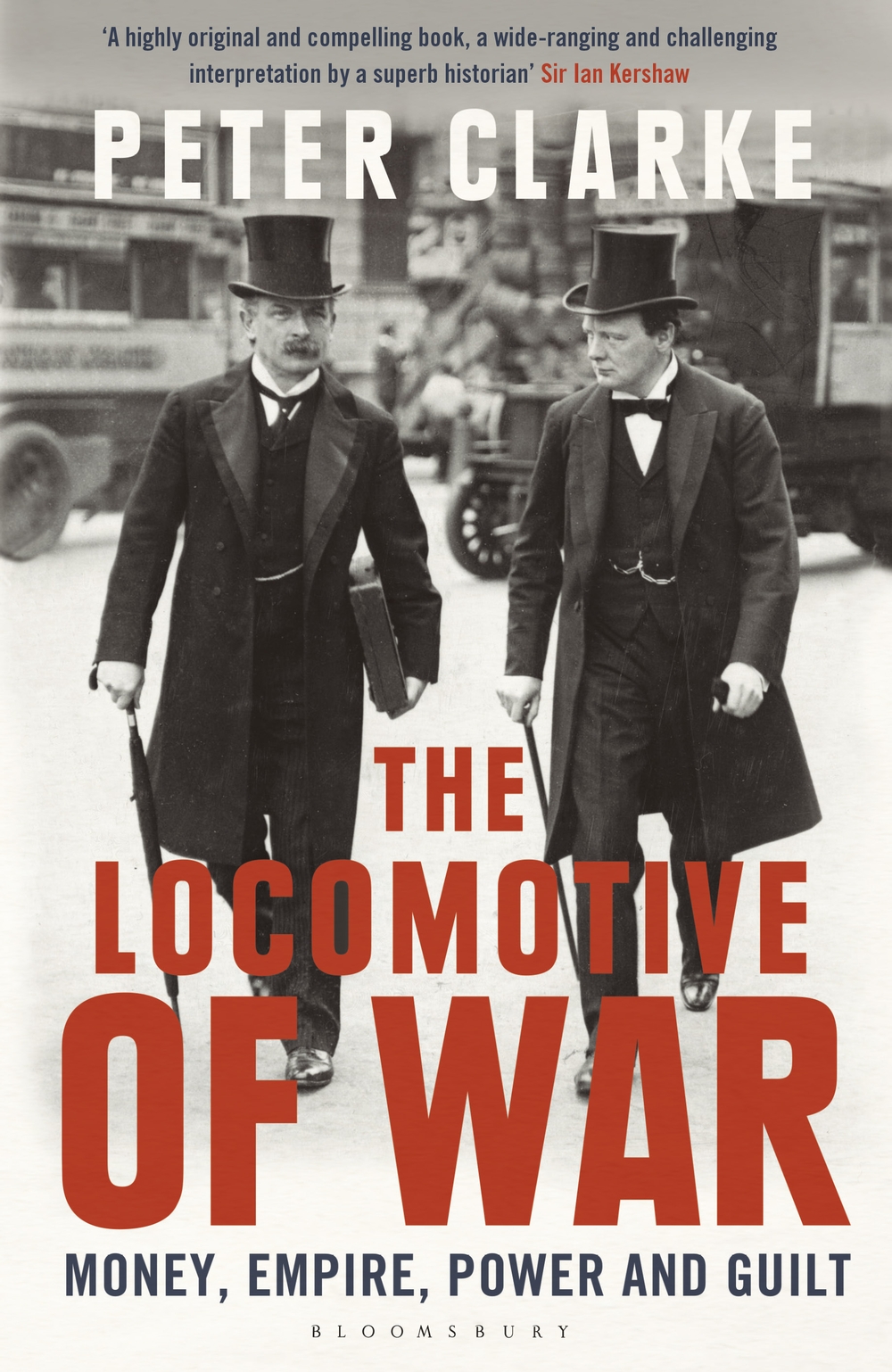

By looking through the spectacles of five prominent figures associated with this tradition of Anglo-American liberalism, we can see these big issues as they saw them at the time. Woodrow Wilson, for whom Gladstone was a boyhood hero; David Lloyd George, with his Welsh background and perspectives; Winston Churchill, a soldier who educated himself as a Liberal statesman; Franklin Delano Roosevelt, an equally privileged knight errant for progressive causes; and John Maynard Keynes, the author of the classic liberal critique of the Versailles peace treaty, warning that if Germany was to be harshly treated in it, "vengeance will not limp".

This is a book that picks up Trotsky's contention that "war is the locomotive of history" to give it a new twist, acknowledging the force of war in making history but in ways far more complex than Trotsky envisaged. Above all, this is a story that develops its own dynamic, with many idiosyncratic features. This is why it is told here not just in terms of Wilson's famous Fourteen Points but by adopting "fourteen points of view" on many of the fascinating issues at stake.

Peter Clarke's latest book, The Locomotive of War, is now available to order through Bloomsbury. Click here to be directed to the book's page on their website.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment