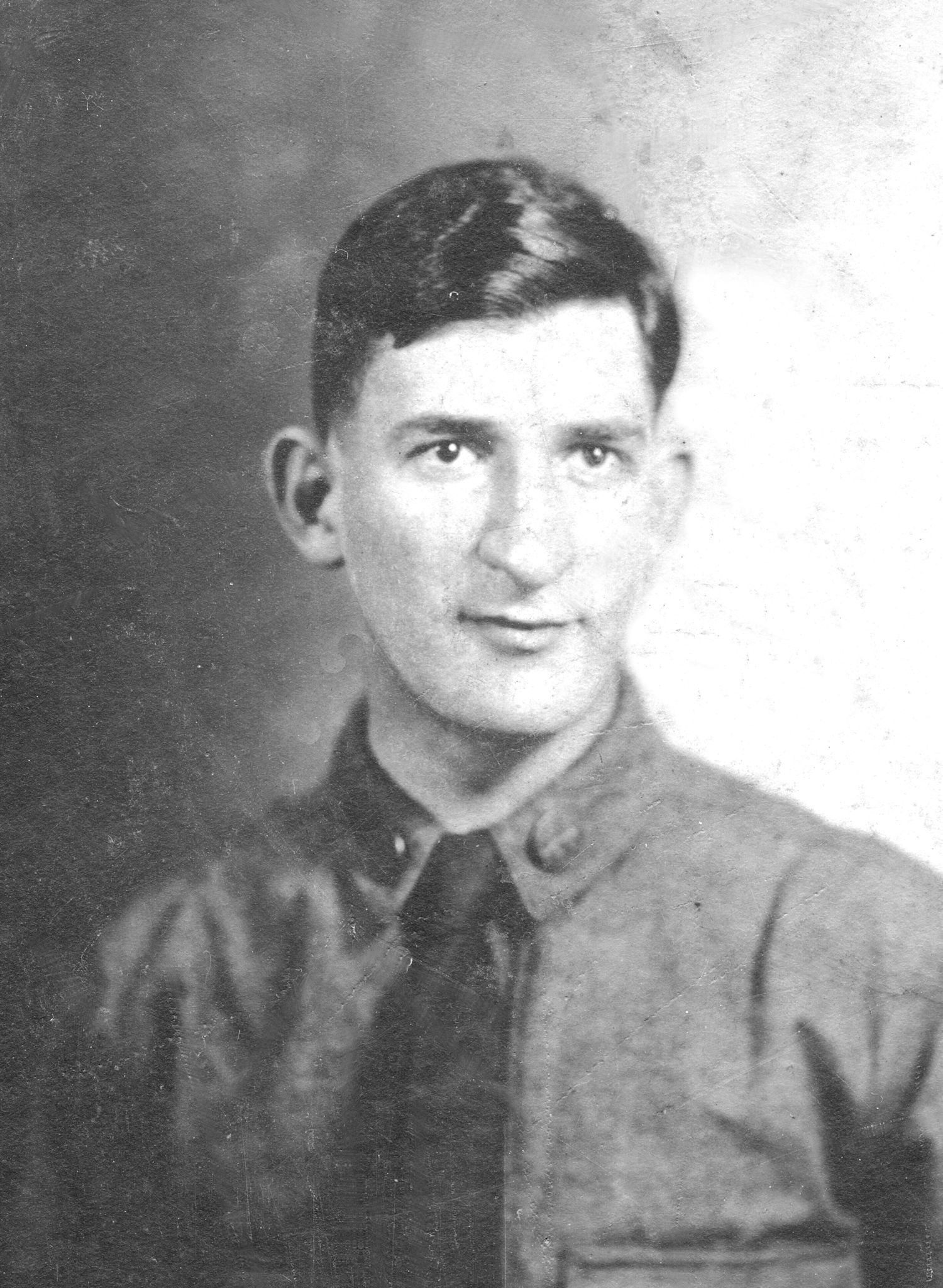

These stories were told to me by my grandfather, former Sergeant Oscar Lubchansky (d. 1958), 2nd Battalion, 313th Infantry Regiment, 79th Division, American Expeditionary Forces. Whether they are historically accurate is debatable, but they are an accurate representation of a veteran’s memories. At this late date, second-hand memories are all we’ve got.

American soldiers had an insatiable appetite for fresh eggs. Whenever Lubchansky and his comrades were en route and a halt was called, the soldiers would crowd around the kitchen door of the nearest farmhouse shouting, “Oofs! Oofs!” The farm wives would be frightened at first, but would soon figure out that the Americans wanted des oeufs and would pay for them. After that, all went well. I have been able to partially corroborate this story. Bruce Bairnsfather, the British war cartoonist, writes in his memoirs about the American soldiers’ astonishing capacity for eggs.

Lubchansky and another soldier were sent to reconnoiter the German front line. He happened to be wearing flared riding pants. While he was lying on the ground observing through his field glasses, a German plane came over and strafed him from dead ahead. The ground around him exploded in dirt and noise, and Lubchansky was momentarily stunned. He couldn’t feel any sensation below the waist. He asked his companion, “Look down and tell me if my legs are still there.” His buddy said, “Yes, but you won’t believe what happened.” The German’s machine guns had shot the flares off both sides of his pants, but left his legs untouched. Although the 2nd battalion was in the thickest of the AEF’s fighting, Lubchansky went through the war unwounded. According to family legend, immediately upon disembarking from his troopship back in the States, he was bitten by a dog.

In the last days of the war, the German soldiers fought fiercely as long as they were protected by their trenches. As soon as an American soldier appeared on the parapet, however, they threw up their hands and shouted, “Kamerad.” At that point, they felt they had done their duty and only wanted to be captured so they could avoid being killed, get a hot meal, and eventually go home. This sounds true, because the German line in Lorraine, by late 1918, was held by static “trench” divisions, as opposed to the better-trained “shock” divisions, which had largely been expended in Ludendorff’s spring offensives. I can still see my grandfather, eyes wide and hands over his head, shouting “Kamerad.”

A squad (section, to the British) from Lubchansky’s platoon was told to take over a ruined château in no-man’s land to use as an observation post. They went forward and occupied the place without incident. Upon settling in, they found that the wine cellar, which had apparently been covered over by shellfire earlier in the war, had been opened up in a recent bombardment. They proceeded to occupy the wine cellar and get royally drunk. While they were there, a large German patrol came forward and occupied the first floor, not noticing the unconscious Americans beneath them. When the main American forces attacked the next morning they chased off the Germans and found their soldiers, still drunk, in the basement. The men were brought before the Major General, who turned to his adjutant and asked what he should do. “I see two choices,” said the adjutant. “You can have them court-martialed for dereliction of duty and drunkenness in action, and possibly shot. Or you can give them medals for holding their position in the face of a superior enemy.” “Which is less paperwork?” asked the general. “The medals,” said the adjutant. “Fine, give them medals,” replied the general. While there are documented accounts of wine cellars being discovered in ruined buildings, I have been unable to corroborate the above story, and it sounds suspiciously like the kind of tale a veteran would tell his grandchildren. But it’s good, so I have always chosen to believe it. There were no real châteaux in the sector of the 79th Division but there were several freestanding “fermes” on the battlefield, assemblages of substantial farm buildings that the Americans sometimes referred to as “châteaux.”

One night, while Lubchansky’s battalion was in the front line, a soldier in his platoon developed an excruciating toothache that left him moaning loudly in pain. Any noise invited fire from the enemy, so this had to be fixed quickly. Lubchansky borrowed a pair of pliers from a nearby artillery battery while someone else produced a contraband bottle of liquor and poured it into the victim. As four strong men held the “patient” down, Lubchansky proceeded to pull teeth in the general area the soldier had previously indicated. When the man stopped moaning, Lubchansky stopped pulling.

© 2017 Gene Fax

Gene's new book, With Their Bare Hands: General Pershing, the 79th Division, and the Battle for Montfaucon, will be published by Osprey in late February 2017, you can pre-order here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment