Once the text, images and artist’s brief have been delivered, the book enters the edit cycle. This follows two tracks: editing text and editing plates. Both generally involve two steps – at least with me. What happens with other Osprey authors may vary. I do not know. What happens in Oxford stays in Oxford. Let me talk about editing the text first. (I always get the text first, even if I deliver the artist’s brief before delivering the text.)

When I deliver the text, I also deliver the images which go with the book. Today they are sent using Dropbox or Wetransfer. Previously I used ftp. Before that I mailed the pictures in the form of 8x10 glossies.

After receiving the text, Osprey’s editorial staff goes through what I sent. The book is received by the commissioning editor, who reads and checks it, and adds comments and queries. It’s then generally assigned to a desk editor who is responsible for shepherding my book through the editorial cycle. I have worked with several over the many books I have written for Osprey. They are an important, but usually invisible part of the process. For World War I Seaplane and Aircraft Carriers my desk editor is Samantha Downes. This is the first time I have worked with her. The desk editor I have worked with most is Nikolai Bogdanovic. Regardless all desk editors proved invariably polite, competent, and enthusiastic.

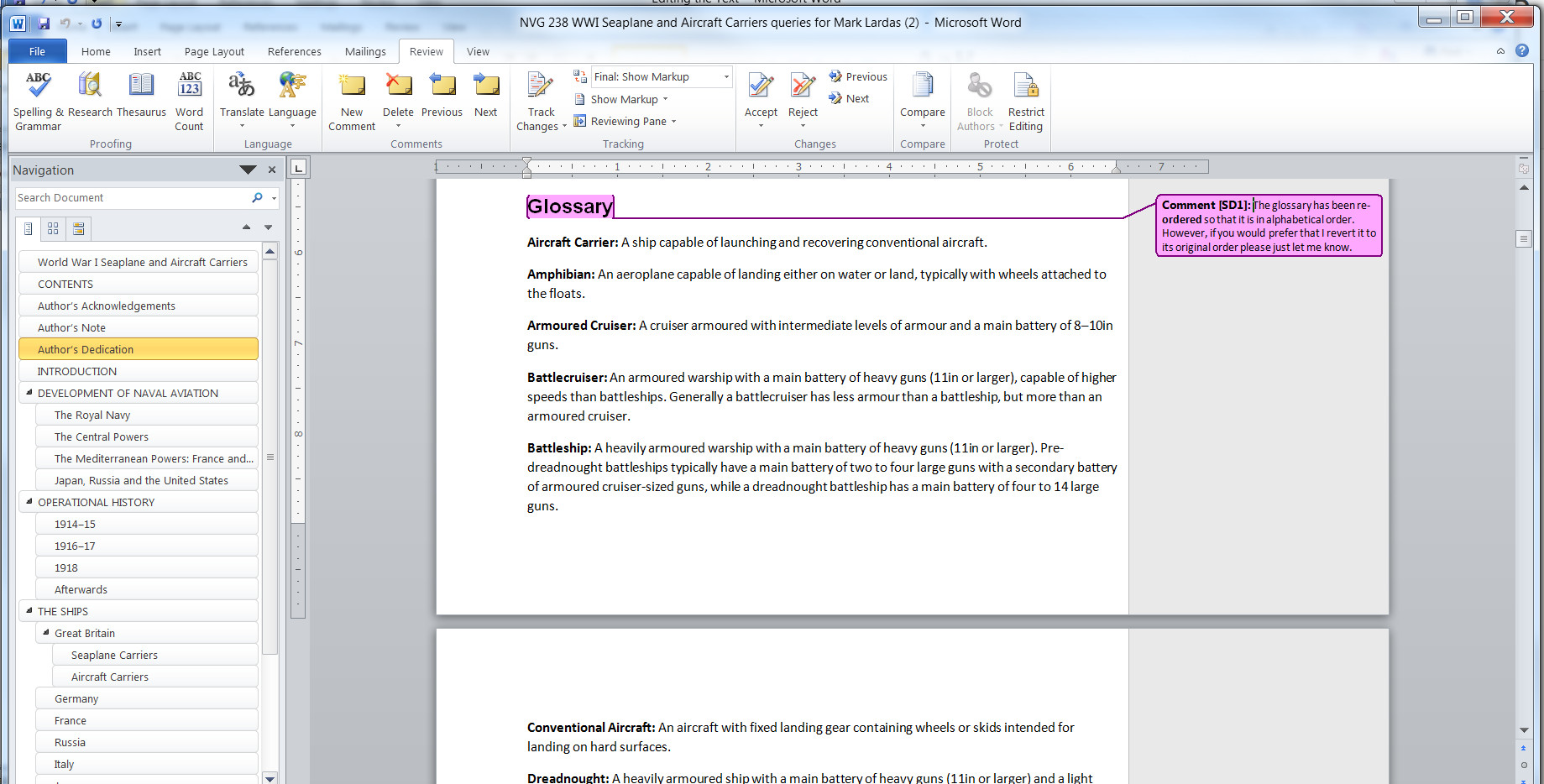

The desk editor starts by picking through my Word file, correcting my spelling solecisms, punctuation errors, and misplaced sentences. This corrected file, formatted in the fonts and styles used by Osprey, but otherwise still a Word file, is emailed to me, with questions about what I have written. Stuff like “Earlier you referred to General Albert Meyers. It is Oscar Meyer here. Which is correct?” These are in comments, with track-changes turned on.

A typical editorial query for me

At this point I am not supposed to do anything other than answer these questions. I generally put them in the comment box posing the question, using red text. If the question involves changing the text, I insert the changes in red in the body of the text. This file contains the body text, but excludes photo captions or plate commentary.

Back in the bad old days, this step was skipped or the desk editor sent a marked-up copy of my original Word file. I like progress. This step goes a long way towards making the editing process easier. I should add I usually get this file four to six months before the publication date.

Shortly after my answers are received and digested by the Osprey Editorial Machine, I receive galley proofs. Back in the day they were overnighted from Oxford to my home in the form of bedsheet-sized. two-page paper proof sheets. I was expected to mark the proofs by hand and return the markups. (Anyone remember what stet means?) Later they sent PDF files.

I was probably one of the last authors to stop asking for paper copies because … well getting them was just too much fun. Seeing the assembled work for the first time, with the pictures in place and printed on sheets large enough to cover the end of a small table? Oooh! I still have most of them, folded in half, in 10x13 envelopes stored in a file cabinet.

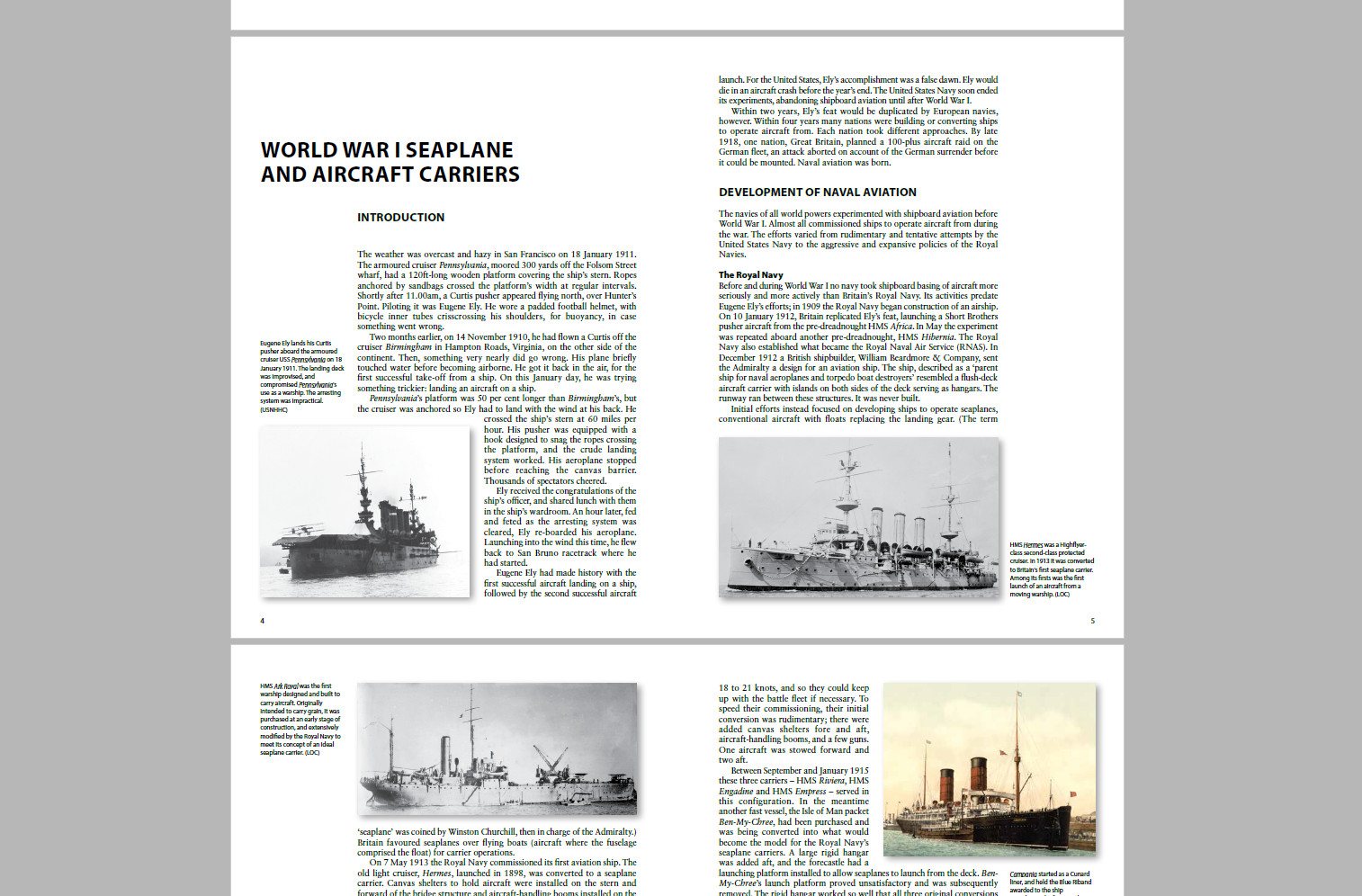

Today I receive a PDF file. It is still a thrill, although they lack the visceral feel of handling physical copies of the proof sheets. Generally the plates artwork is missing, but the captions and plate commentary are there. The PDFs beat old paper galleys on image quality though. The old galley images were low-resolution versions. With the PDFs they are sharp. Not as sharp as the actual book, but pretty good.

The galleys - it does not get better for an author

I go through these for errors and correct them. Or maybe decide something was not stated quite clearly enough. Please note – errors are my responsibility. I am supposed to check all the various tables and make sure the numbers are correct. If the text says 663 tons and it is supposed to be 63 tons, I am expected to fix that. Osprey assumes I know this stuff.*

The biggest pain with WWI Seaplane and Aircraft Carriers was checking all of the values in the Ship Histories section. I went through each ship with the PDF on my monitor, and my source books in front of me. I bet I still managed to drop stitches. Human brains are remarkably adept at seeing what is expected instead of what is there. (Don’t believe me? Watch this.)

What about the plates? We talk about those next.

* Editor’s note: Well, up to a point. Although we editors are unlikely to be experts on any given subject, we also go through every book looking obsessively for errors and possible errors – anything implausible, anything that we happen to know is wrong, anything that’s doesn’t match what’s said elsewhere in the book, anything that trips that editor’s internal alarm that says ‘wait, is that really right?’ The fewest mistakes will creep through when everyone assumes it’s their job to spot mistakes.

| Previous: Putting Text to Paper |

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment