The Eastern Front of World War II was the most significant and ferocious theatre of the conflict. In four unremitting years of war, millions of soldiers fought along a staggering 1,600 mile long front which stretched from the ice of the Arctic Circle to the rugged mountains of the Caucasus.

To celebrate the publication of Atlas of the Eastern Front: 1941-45, we have pulled two extracts from the book's section on the titanic Battle of Stalingrad, complete with two stunning maps. The first depicts the initial German offensive in the autumn of 1942, and the second the final destruction of Paulus's 6. Armee in January 1943.

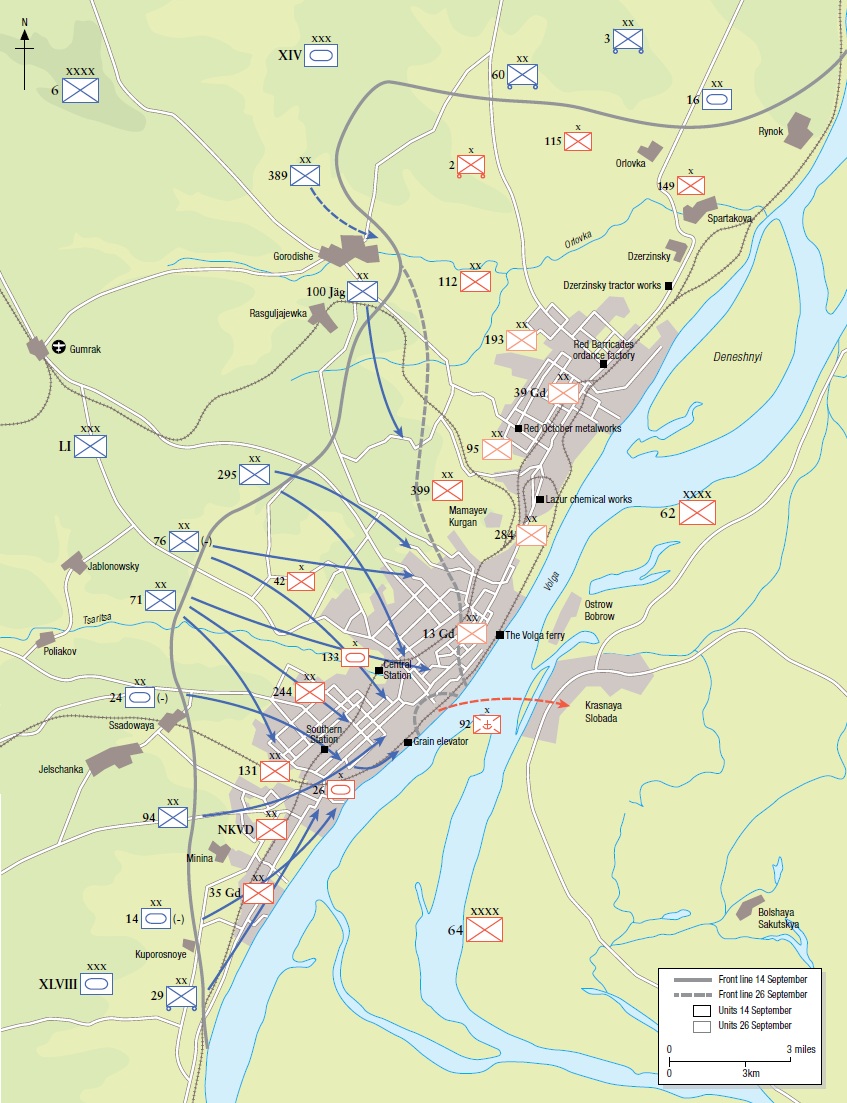

Map 52: Stalingrad (I) – 14 to 26 September, 1942

Extract

"The German attack began at 0630 on 14 September and made good progress in the centre and south. By noon they had progressed through the suburbs and into the city centre, using artillery to kick Chuikov from his command post on the Mamayev kurgan (burial mound, also known as hill 102) a couple of hours later. The 4. Panzer-Armee assault parties reached the Volga in numerous places and approached the large grain elevators. Both the central and southern train stations seemed in danger of falling to the Germans. The 71. and 76. Infanterie-Divisionen made spectacular advances into the city centre and threatened to chase Chuikov out of another command post. Eremenko rushed reinforcements including the 13th Guards Division across the broad river and into the fight. In the south the battle stabilized with the Red Army still in possession of the grain elevator. On the 15th, the central railway station changed hands numerous times, but by nightfall it too remained in Soviet possession.

Stalingrad was in real danger of falling on 14 September when Hoth’s 24. Panzer-Division reached the Volga and then wheeled north, threatening to roll up both the 64th and 62nd Armies. A day later, Stalin dispatched two brigades across the river to further secure the ferry-boat staging area and to halt the panzers. The latter, the 92nd Naval Infantry Brigade, arguably saved the day. For his part, Hitler gave Paulus overall control of the Stalingrad battle, detaching the XLVII Panzer-Korps from Hoth. Given the inexperience of Paulus contrasted with Hoth’s excellent field leadership throughout the first three years of World War II, this was a curious, if not decisive, decision. By the 18th, 71. Infanterie-Division indeed forced Chuikov out of his Pushkin Street command bunker, while the 13th Guards almost ceased to exist. Eremenko was becoming desperate, and 24 hours later began launching low-odds counterattacks everywhere.

With both sides nearing exhaustion, by the third week of September the battle hung in the balance. As of the 21st, only the 92nd Naval Infantry remained south of the Tsaritsa River. In the centre, the Soviets held only a few slivers of land right on the Volga banks. They had lost many ferry-boat staging areas, absolutely critical to keeping the defence of Stalingrad going. Desperate counterattacks on the 22nd, they failed to lever the Germans off their hard-won positions. On 22 September, troops belonging to XLVIII Panzer-Korps captured the grain elevator and the following day the 92nd Brigade withdrew to the far bank of the Volga. Paulus’s men had suffered grievously as well, but appeared on the verge of victory."

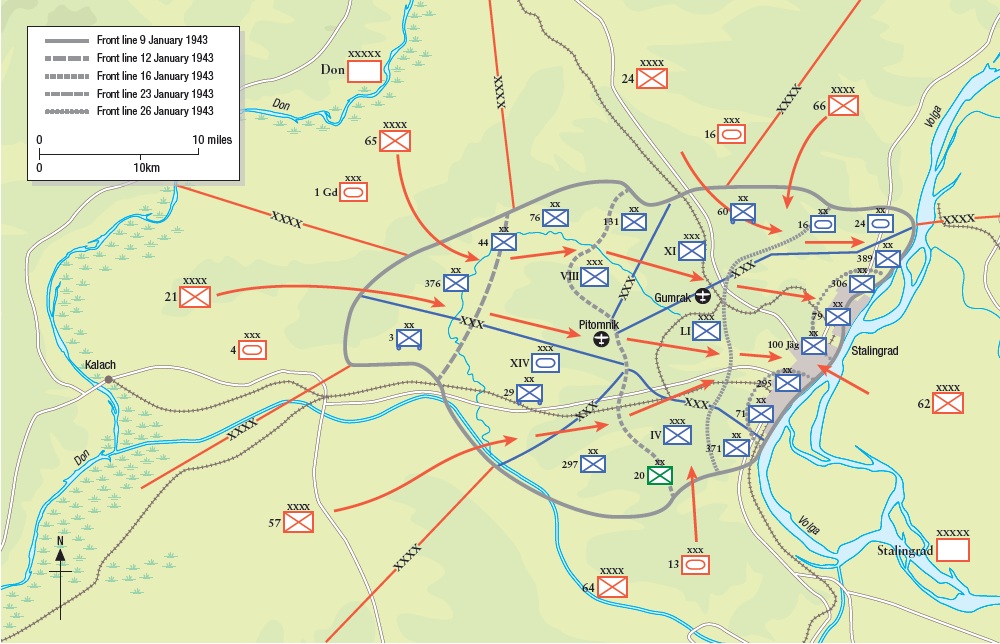

Map 59: Operation Koltso (Ring), 10 January to 2 February, 1943

Extract

"Seven Soviet armies encircled 6. Armee’s 20 German and two Romanian divisions. On 25 November the first Luftwaffe supply planes arrived, but they could never make good on Göring’s boast to fly in 600 tons per day. Paulus planned an all-around defence, but by the end of the month had lost half the pocket’s territory, finally halting the Soviets in early December. Distracted by Little Saturn and Wintergewitter (against which Operation Koltso’s main effort, 2nd Guards Army, was dispatched), the Red Army settled for pounding the Stalingrad pocket with artillery. Attrition and wastage reduced the 6. Armee’s actual combat strength to a small fraction of its quarter of a million reported strength. Rokossovsky’s seven armies included only slightly more men, but they enjoyed superior morale and logistics.

On 8 January the Soviets issued a surrender ultimatum to Paulus, which he rejected. Two days later, 21st and 65th Armies launched Koltso from the west and within two days had pushed three German divisions out of ‘the Nose’ and behind the lower Rossoshka River. After a week of fighting, and joined by the 57th, 24th and 66th Armies, they had overrun the western half of the pocket, including the Pitomnik airfield. From the German point of view this looked disastrous, but the Soviets were dismayed by their failure to land the knockout blow. Wehrmacht numbers far exceeded the Stavka’s intelligence estimates. Rokossovsky paused to re-organize and then resumed his assault against the northern perimeter on the 20th. In these two weeks, 6. Armee’s combat strength had dropped from 80,000 to fewer than 20,000.

Rokossovsky resumed his attack on 22 January with the 57th Army leading the way from the south-west. Paulus wanted to surrender on humanitarian grounds, but this argument had no effect on Hitler. By this time, 6. Armee was mainly a collection of the unattended wounded, sick and starving. The Soviets captured Gumrak airstrip on the 23rd and the Mamai kurgan two days later; the 62nd and 21st Armies had split the pocket in two. On 29 January the southern group was further subdivided. Germans in the northern pocket began surrendering the next night, while Paulus waited until the last day of the month to do so. The remnants of six divisions of XI Armee-Korps held out around the tractor factory until 2 February. German losses amounted to nearly 150,000 dead and more than 90,000 taken prisoner. Soviet casualties totalled 1.1 million, including almost 500,000 dead."

Altas of the Eastern Front: 1941-45 by Robert Kirchubel will be published on 20 January worldwide and can be preordered today.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment