Tonight on BBC Two is the season premiere of The Last Kingdom, the television adaptation of Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon Stories. It is a series that has got everyone at Osprey excited, and so we’ve decided to bring you a number of blogs to complement the series. To start off here is an introduction to Saxons and Vikings.

Introduction to the Saxons:

Extract from Men-at-Arms 85: Saxon, Viking and Norman by Terence Wise

When the Roman government of Britain collapsed in the early 5th century, the romanized native population struggled for a time to preserve its Roman way of life, but gradually this was submerged by invaders from the Continent. These invaders came from three powerful Germanic nations: Saxons from northern Germany and Holland; Angles from the south of the Danish peninsula, an area still known as Angeln; and Jutes from Jutland. At this time, the Migration Period, there were similar tribal movements taking place throughout Europe and it is probable that the Angles, Saxons, Frisians and possibly even the more independent Jutes were by this date more or less identified with each other, forming an Anglo-Saxon people of mixed stock but with a number of common characteristic. The invaders are thus usually termed Anglo-Saxons for convenience.

The first Anglo-Saxons to reach Britain came by invitation, possibly even before the Roman government had collapsed. They came in war bands, under their own chiefs, as mercenaries to help defend Britain against attacks from Ireland, Scotland and the Continent. These first small groups later combined into larger units and began to colonize Britain, sending word to their homelands of the easy pickings. Larger-scale invasions followed.

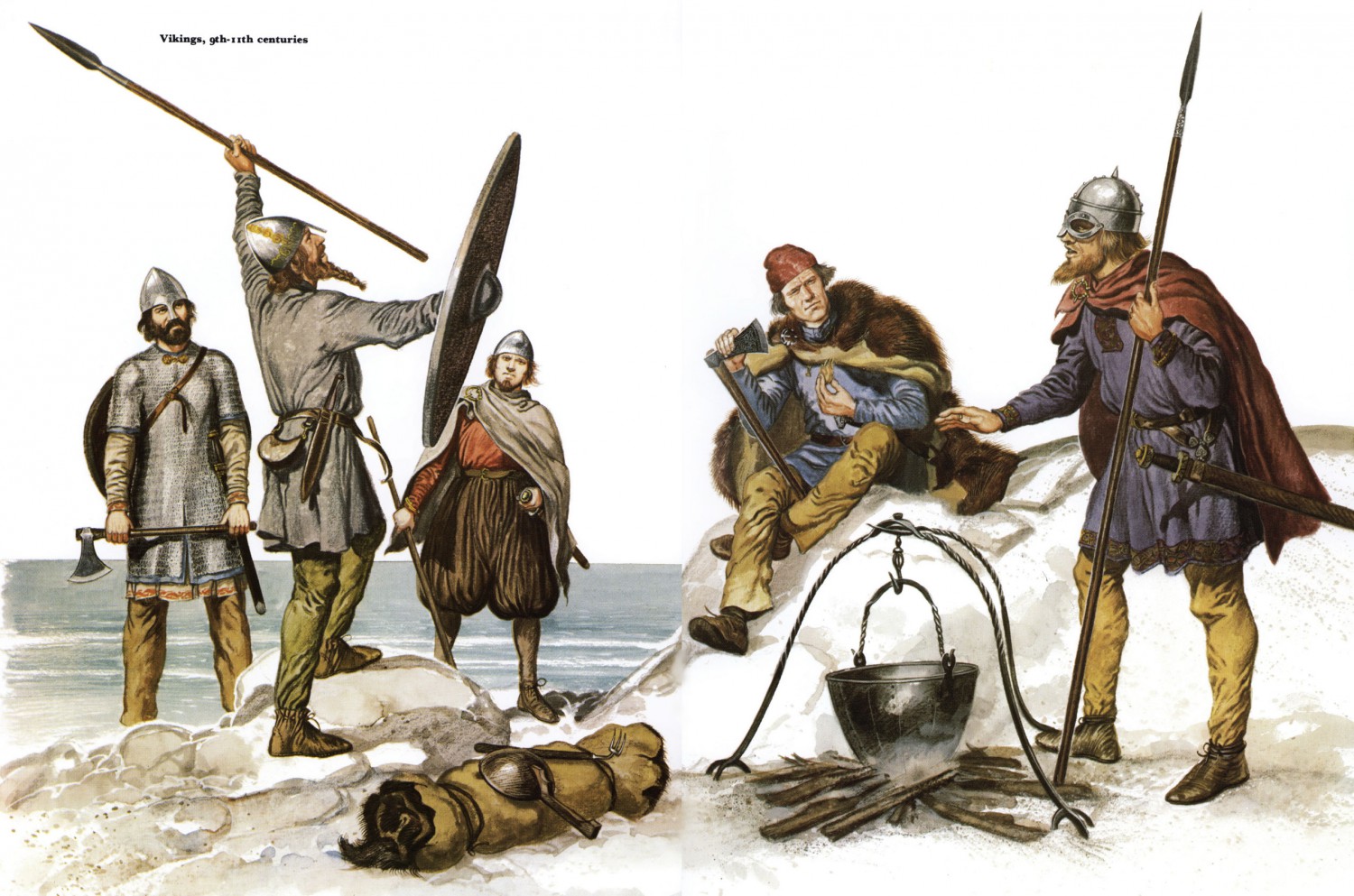

Illustration by Gerry Embleton

Illustration by Gerry Embleton

The most important invasions by these mercenaries-cum-colonists were c. 440–460. Legendary leaders, such as Hengist and Horsa, employed originally by King Vortigern in the south-east to repel the Picts and Scots, soon rebelled against their employers and began to establish petty kingdoms. The native population put up a considerable resistance to the expansion of these kingdoms, particularly under such military leaders as Ambrosius Aurelanius and Arthur; but gradually, over a century and a half they were reduced to a subject people, or fled into the hills of the Celtic lands to the west and north. By the time of the Augustinian mission to England in 596 (felt necessary to rescue Christianity in what had now become a pagan land –the land of the English) the Anglo-Saxons controlled the whole of the south coast from Kent to east Dorset, from the east coast (from the Thames to the Humber) across to the lower Severn, modern Staffordshire, Derbyshire, most of Yorkshire, and part of Northumbria and Durham. There is much confusion over which tribes settled where, but broadly speaking the Jutes controlled Kent, the Isle of Wight and part of Hampshire; the East, West and South Saxons controlled Essex, Wessex and Sussex respectively; and the Angles controlled East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria.

By the beginning of the 7th century there were about a dozen independent kingdoms, with the main power in Northumbria, and in the first half of the century the Northumbrian kings almost established themselves as permanent overlords for the whole of England. But in 648 the Mercians revolted and ended all hope of unity for another century. Gradually in the second half of the century the centre of power shifted from Northumbria to Mercia, with Essex, East Anglia and London being absorbed into that kingdom by 670. Sussex, Wessex and the Isle of Wight subsequently became subjected to Mercian rule and by the reign of Offa (747-796), the strongest of the Mercian kings, he was able to describe himself in one of his charters as ‘King of the whole of England.’

His successor died in 821 and there followed a series of campaigns by the king of Wessex as he attempted to bring the whole of England under his control.

Introduction to the Vikings:

Extract from Men-at-Arms 85: Saxon, Viking and Norman by Terence Wise

The Viking Age can conveniently be defined as commencing with the first raid on Lindisfarne in 793 and ending with the defeat of the army of Harald Hardraada at Stamford Bridge in 1066. However, this is a prejudiced view, a time limit set by those who suffered at the hands of the Viking raiders, for the Vikings were on the move as traders and settlers long before 793, while the end of the Viking Age was brought about as much by Christianity as by the success of the Anglo-Saxons at Stamford Bridge.

Whatever the exact chronological definition of the Viking Age, the Viking raiders burst suddenly into the mainstream of history in 793, terrorizing most of the then-known world, founding earldoms and kingdoms from the Thames to the Volga, and having a profound effect on the making of modern Europe. ‘A furore normannorum libera nos, Domine’ (‘From the fury of the Northmen deliver us, O Lord’) prayed Christians throughout Europe but it would be two and a half centuries before their prayers were answered.

Where did the Vikings come from, and why? They were Swedes, Danes and Norwegians, Scandinavians from a self-contained northern society which spoke a common language and shared a common culture. Originally traders, whose trading posts in foreign lands frequently grew into colonies, they leave us evidence that just prior to the beginning of the Viking Age there was a marked population explosion. The limited farming lands of Scandinavia could not support the increased population, and large-scale expansion began: as early as 810, raids were being co-ordinated to obtain not just loot, but land.

Illustration by Gerry Embleton

Illustration by Gerry Embleton

It was the Norwegians who began the raids, but the Danes and Swedes soon followed suit. Sweden faces the east, and the Swedes naturally thrust across the Baltic and into the steppes of Russia, following the rivers and lakes, down the Volga and Dnieper towards the great trading centres of Baghdad and Byzantium. Their own main trading centres were established at Novgorod, Kiev and Smolensk, and their leaders ruled here as princes. The Vikings called these lands Greater Sweden, but the Arab and Byzantine writers of the 9th and 10th centuries, in their frequent mentions of the Vikings, referred to them as Rus (probably a corruption of the Finnish word for Sweden, Ruotsi), and thus the Vikings both created and gave their name to Russia.

The Danes and Norwegians generally sailed south through the North Sea to western Europe, Britain and Ireland. At first the Norwegians pillaged and settled in the Orkneys, Shetlands, Hebrides and Isle of Man. From these bases they turned on Ireland, raiding year after year until by 845 they had established fortified harbours from Galway to Cork, and could ravage the whole of Ireland at will. No attempt was made to subjugate the country; instead, the Norwegians built Ireland’s towns – Dublin, Limerick, Waterford, Wicklow and Wexford – all trading centres. As in Russia, the Vikings then gradually merged with the local population until in 1014 the last of them were defeated at the battle of Clontarf by the army of Brian Boru, High King of Ireland.

In 834 the Danish Vikings first appeared in force, raiding along the English Channel. Thereafter they appeared annually. Their effect is best described by a monk, writing at the time: ‘The Vikings overrun all that lies before them, and none can withstand them. They seize Bordeaux, Périgueux, Limoges, Angouleme, Toulouse; Angers, Tours and Orléans are made deserts. Ships past counting voyage up to defeat the Danes in the south, but he could not save the north-east, and the wide belt of land between the east coast from the Thames estuary almost to the Tees, and the west coast from Liverpool to Carlisle, was ruled by the Danes and became known as the Danelaw.

Further Reading:

Looking for books to read alongside The Last Kingdom? Here are some that complement the series:

Men-at-Arms 85: Saxon, Viking and Norman

Warrior 5: Anglo-Saxon Thegn AD 449–1066

Elite 3: The Vikings

Warrior 3: Viking Hersir 793–1066 AD

Men-at-Arms 154: Arthur and the Anglo-Saxon War

Fortress 14: Fortifications in Wessex c. 800–1066

New Vanguard 47: Viking Longship

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment