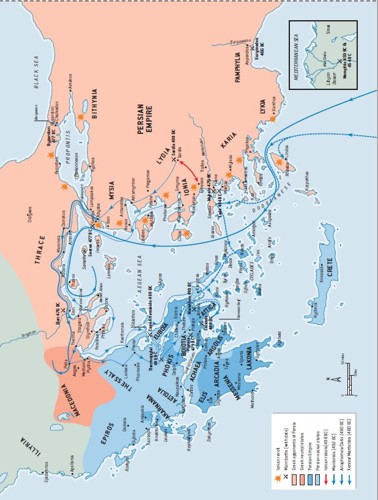

Athenian Trireme

Factfile

• Hipponax of Ephesos and later Klazomenai, a 6th-century bc iambic satirist, is the first Greek writer we know of to mention the triērēs, trireme.

• Thucydides (1.13.2–3, cf. Plin. HN 7.57), who himself commanded triremes in the Peloponnesian War (431– 404 bc), credits the Corinthians as being the first of the Greeks to build triremes, and 300 years before the end of the war (either the Peace of Nikias, or the end of the Peloponnesian War, viz. 721 bc or 704 bc) Ameinokles, a Corinthian shipwright, built four triremes for the Samians, though it must be emphasized the Samians were still using a greater number of pentēkóntoroi than triremes as late as 540 bc (Hdt. 3.39.2, 3.44.2). Even so, there is a gap of a good 150 years between Ameinokles’ triremes and Hipponax’s poetic reference to a trireme.

• By 483 bc Themistokles was the most influential politician in Athens, and as he believed that the Persians would return, he favoured the expansion of the Athenian navy to meet the next threat.

• On the eve of Xerxes’ invasion, having performed a labour fit for the monster-slayer hero Herakles (Hercules), the Athenians had at least 200 triremes of their own fully equipped and ready for service.

• If Plutarch is correct, in his naval bill Themistokles had specified that Athens’ new warship should be fast triremes: light and open for greater speed and manoeuvrability.

• To reiterate, only a simple canopy deck (without guardrails) connected the helmsman’s small quarterdeck to the foredeck at the prow where the bow officer was stationed. A gangway ran down the middle of the trireme, giving access to the interior. The new Athenian triremes were designed for ramming attacks, not for carrying large contingents of fighting men.

• By committing themselves completely to this design, Themistokles and his fellow Athenians were taking a calculated risk. For many naval actions, both at sea and of an amphibious nature, fully decked triremes would have been more serviceable.

Trireme statistics (based on Olympias)

- Length: 36.8m

- Beam (hull): 3.65m

- Beam (outriggers): 5.45m

- Draught: 1.2m

- Total displacement: 42 tonnes

Ship’s complement (based on Athenian naval inventories)

- Crew: 200, comprising:

- 170 oarsmen (nautai), comprising:

- 62 upper oarsmen (thranitai)

- 54 middle oarsmen (zugioi)

- 54 lower oarsmen (thalamioi)

- 14 armed men

- 10 citizen marines (epibatai)

- 4 Scythian archers (toxótai)

- 16 specialist seamen

- 1 trireme commander (triērarchos)

- 1 helmsman (kubernētēs)

- 1 bo’sun (keleustēs)

- 1 bow officer (prōratēs)

- 1 shipwright (naupēgos)

- 1 double-pipe player (aulētēs)

- 10 deck-hands

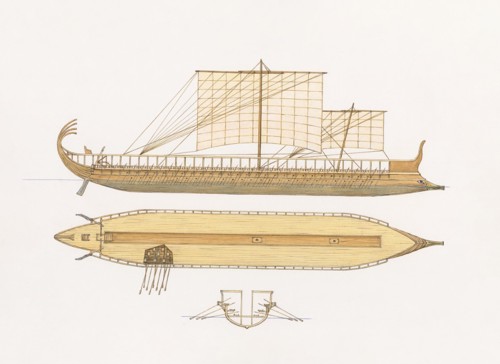

- In general, the trireme was a sleek wooden oar-powered warship armed with a bronzesheathed waterline ram (Gk. émbolos). Because she was designed primarily to act as a buoyant projectile for ramming enemy vessels, the trireme was very long and narrow for her length and beam, which made it as fragile as it was fast.

- Besides the inadequate data concerning its true origins, for the design of a trireme we rely upon scraps of textual and archaeological evidence.

- A trireme was rowed at three levels with one man to each oar. A chance remark by Thucydides, in which each Corinthian oarsman of a trireme is said to have ‘carried his oar, his cushion (hypērésion) and his oar-loop’ (2.93.2) from one side of the Isthmus to the other so as to launch a sneak attack on the port of Peiraieus, proves there was one man to each oar.

- An oar was held in place by a leather strap, sewn into a loop (Hom. Od. 4.782); this was the oar-loop. The oar-loop held the oar tightly against an upright, wooden peg; this was the tholepin (Gk. skalmós). Again, Aischylos provides further evidence for the oneman- to-an-oar hypothesis when he uses the synonym trískalmos (Pérs. 679), literally ‘with three tholepins’, to describe a trireme.

- these oars were of two marginally different lengths, nine cubits (3.99m) and nine and a half cubits (4.2m) long (based on the 0.444m cubit), the slightly shorter oars being needed where the hull narrows at either end, towards bow and stern, restricting the room available to the oarsmen operating there. The odd 21cm would have been taken off the inboard end of the oars, the loom, leaving the outboard oar the same length as all the others.

- The excavated remains of the Zea ship sheds (Gk. neōsoikoi) at Peiraieus, built for triērēs, give the maximum dimensions for the ships (Athenian), that is, 37m long, 3m at the hull, increasing to 5.5m at the outriggers.

- The draught of these ships was relatively shallow, about 1.2m.

- Enlarging their ships the Phoenician shipwrights provided enough height and space to fit three levels of oarsmen within the hull. The Athenian trireme differed from the Phoenician original by only having the first two levels of oarsmen within the hull, the second level working on the gunwale and the first through ports lower down. This was achieved by the invention of the parexeiresía, the apostis of more recent galleys and what we call the outrigger, a frame-like structure outside the hull and running parallel with it from stem to stern, to provide a working-point for the third level of oars beyond the side of the true hull. The name parexeiresía, which is used by Thucydides (4.12.1, 7.34.5), ‘along (para) – outside (ex) – rowing (eiresía)’ describes the purpose of the structure.

- There was a refitting programme to make the Athenian triremes originally built under Themistokles, then some 15 years old and built en masse and in a hurry, ‘broader and given a (greater) deck span’ (Plut. Kim. 12.2), perhaps showing Phoenician influence, carried out by Kimon just prior to his amphibious operations in Ionia.

- Triremes were built using the shell-first method, as opposed to skeleton-first, a skill whereby the ancient shipwright essentially shapes the hull with adjoining planks. These planks were firmly joined together edge-to-edge by large numbers of closely spaced tenon tongues fitted tightly into individual mortise slots cut into the plank edges.

- Next, when the closefitting seam had been made, the tenons were pegged in place. This shell-first method is brilliantly described by Homer in his quintessential sailor’s story, the Odyssey (5.243–61).

- For strength, tenons were made of a selected hardwood, most likely Turkey oak (Lat. Quercus cerris), a wood common in the region in antiquity, and cut with their grain end-to-end at right-angles to that of the planks.

- The keel was the first and foremost important element of a trireme’s construction. In order for the vessel to achieve its intended performance ability, the keel needed to be hewn correctly to receive and support shell planking, wales, and frames.

- Framing was secured to the shell planking by copper spikes, which had tapered square shanks and large shallow-domed heads. These spikes were driven up pinedowels previously driven up holes bored through plank and framing. The points of the spikes were clenched over and driven back into the face of the framing.

- So, to strengthen a hull made in this way the Greeks used devices called ‘undergirdles’ (hypozōmata). These were probably heavy ropes fitted low down in the ship and stretched by means of windlasses from stem to stern.

- The primary weapon of a trireme was the bronze-sheathed waterline ram (Gk. embólos) situated at the prow.

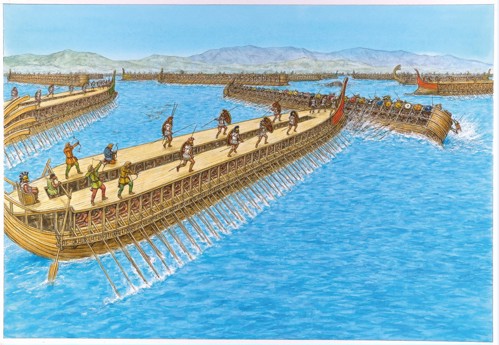

The Battle of Salamis. In the main illustration, an Athenian trireme has ploughed into the midships of a Phoenician one, smashing a hole, and they are now locked in a deadly embrace. Persian marines from the Phoenician vessel are attempting to board the Athenian one before their vessel flounders; the Athenian marines are rushing towards the prow in an effort to repel them. On a 70m-high eminence on the lower slopes of Mount Aigaleos overlooking the Salamis Strait, Xerxes has established his command post, seated on his well-known but misnamed ‘golden throne’ surrounded by members of the Immortals and attendants. Themistokles sits on the quarterdeck of his trireme, clad in decorated linothōrax and buffed bronze greaves and holding his Corinthian helmet. In the thick of the battle, Artemisia has perceived things are going badly for the Persians. The time has come for the Karian queen to look to her own survival. (Illustrated by Adam Hook)

From Duel 122 Athenian Trireme vs Persian Trireme: The Graeco-Persian Wars 499–449 BC by Nic Fields