The Augustan Age poet Publius Ovidius Naso (known to us as Ovid) is perhaps best known for his love poetry (the Amores and Artis Amatoriae) or his Metamorphoses. He is not a go-to source for military insights and yet, at the end of his career, he was apparently exiled to Tomis (modern Constanța, Romania), in the land of the Dacians, and there he witnessed and experienced life on the edge of the Roman Empire. He wrote two poetical works while in exile and they record remarkable details of the harsh life on the imperial frontier, constantly surrounded by Dacian enemies.

At certain periods during the 20th century, it became fashionable to consider that the exile Ovid was a fiction, an ironic literary figment of the poet’s imagination. According to the orthodox version of these events, Ovid was exiled to Tomis, on the Black (Euxine) Sea, at the very far edge of Roman influence, by the Roman emperor Augustus in AD 8. He would remain there for the rest of his life, dying in exile in approximately AD 17/18. In Ovid’s poems, especially the Tristia and Epistulae Ex Ponto, the story of how this exile came about is only tantalisingly suggested (we never learn what actually happened). Even though he was banished by Augustus, Ovid remained in exile for four years after Augustus’ death in AD 14 under his successor Tiberius – this too remains unexplained in Ovid’s writings.

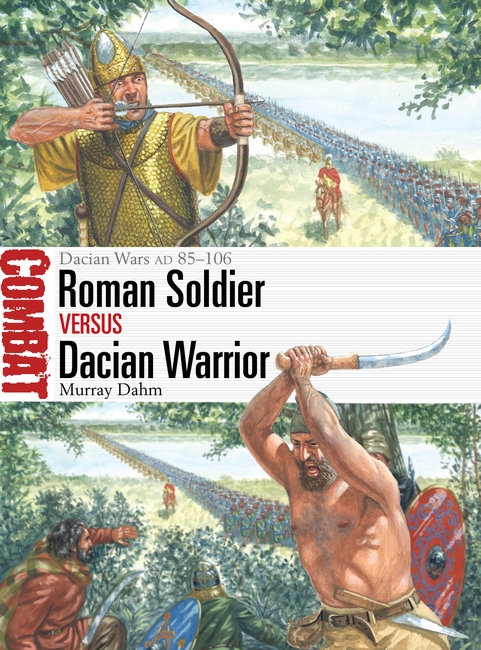

Ovid paints a vivid (if depressing) picture of life among the ‘scarcely pacified’ Getae and Sauromatae (he uses several names for the tribes of Dacians or Geto-Dacians, including Scythians), and of a place constantly in danger from roving bands of wild barbarians. The Getae were considered synonymous with the Dacians or a subset of them; alternatively, the Dacians were considered a subset of the Getae. They were a liminal people to Rome when Ovid wrote, but they and Dacia (corresponding largely to modern-day Romania) would become the hot-spot of campaigns of conquest for 20 years under Domitian (r. 81–96) and Trajan (r. 98–117). It is these campaigns I explore in Roman Soldier vs Dacian Warrior – the campaigns conducted by Domitian (AD 86–88) and by Trajan (AD 101–02 and 105–06).

Ovid provides several unique insights into the warfare of the Dacians and Getae and the Sarmatians who surrounded and threatened Tomis. It is an evocative picture that does much to add to our understanding of warfare on that edge of the empire. Ovid also provides remarkable insights into the defence of a small, relatively unimportant community on the edge of Roman influence. We can corroborate Ovid’s picture with that of another exile, Dio Chrysostom, who travelled among the same Dacians in the 90s AD and was there when Domitian died, assassinated in AD 96. The two men’s pictures, some 80 years apart, is largely the same, and so we can use Ovid’s details to tell us about the Dacians at the time of Domitian’s and Trajan’s campaigns against them.

Ovid loathed his exile and his picture is consistent across his almost ten years of writings there. He was sent into exile when he was aged 50 and despite the fact that he was Rome’s most popular living poet. The picture of his exile and the struggles he faced is, no doubt, exaggerated, but Ovid paints an unrelentingly bleak portrait. Despite the poetic exaggeration of how much Ovid detested his place of exile and the uncouth and uneducated people among whom he found himself, he gives us details which are accurate (such as the topography of Tomis) and – if we buck the trend and accept his exile as a reality – he actually gives us insights into the military history of the region that no other author does. For that fact alone, it is worthwhile exploring in detail exactly what he tells us.

There are problems, however. The view which became popular in the 20th century was that Ovid had never set foot in Tomis at all and his entire exile was invented; it was ‘ironic’. There are many mysteries and apparent oddities in the story of Ovid’s exile and there is an extensive bibliography on the exile itself, let alone those who would see it as a literary and poetic fiction. The exaggeration of his circumstances and the constant threat of violence seem at odds with our picture of the Pax Romana of Augustus, but Tomis was, admittedly, on the very outer edge of Roman influence. What is more, Ovid did not lose his rights as a citizen or his property; he was a relegatus rather than a true exile (Tristia 5.11.15).

One of the lynchpins of the arguments that Ovid’s exile was a fiction (especially those of Fitton Brown and Gareth Williams) is an insidious argumentum ex silentio: later historians such as Tacitus, Suetonius and Dio Cassius do not mention Ovid’s exile so it must not have happened. If we were to take silences, even unexpected and accumulated ones, as evidence something did not happen in ancient history, we would need to abandon all manner of material taken as certain – are we to reject everything Plutarch wrote because no other writer in antiquity mentions him? Yet, there are other authors who mention or allude to Ovid’s exile (see Pliny, Historia Naturalis 32.54; Epitome de Caesaribus 1.24; Statius, Silvae 1.2.255; Jerome, Chronicle 2030.4 for AD 17). These, conveniently for the arguments which would have Ovid’s exile a fiction, are rejected as peripheral or late. The other argument, that all Ovid tells us of Tomis he could have obtained from other authors, can be put to the test with the military insights he provides.

Ovid tells us that two crimes (duo crimina), a poem (carmen) and an error (error), were the cause of his exile but that he must keep silent on his guilt (culpa) (Tristia 2.207-208); he never goes into more detail. What the exact crimes were and what the error he committed was never specified, and these have led to a great deal of speculation. Modern scholars have hypothesised (probably correctly) that the poem in question was the Artis Amatoriae (or Ars Amatoria, the Art of Love) that led to Ovid’s exile from an Augustus keen to impose strict moral laws. Those laws had begun to be passed in 18/17 BC; especially the lex Iulia de adulteriis (which made adultery a crime) and the lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus (which actively discouraged bachelorhood). Ovid’s Artis Amatoriae was, more or less, a handbook on how to conduct an affair, and so is considered at odds with Augustus’ laws.

The Artis Amatoriae had, however, first appeared in 1 BC and Ovid was not exiled until the autumn of AD 8 – more than 25 years after the morality laws were announced and nine after the work in question had first appeared. Ovid never explicitly tells us it was the cause of his exile, although he does state (Tristia 2.211-212) that he was charged with teaching adultery by an obscene poem (turpi carmine) and this certainly sounds like the Artis Amatoriae.

Ovid also (somewhat vaguely) blames the nine muses in general for his exile – his poetry was to blame (Tristia 5.12.45–46). The first edition of Ovid’s love poetry, the Amores, had appeared in about 20 BC (or perhaps 16 BC, so after the laws) and the Heroides – letters from wives to the (absent) husbands – was published after the Amores and before the Artis Amatoriae. His later poems, the Metamorphoses and Fasti were begun after AD 2 but not completed when he was exiled; the Metamorphoses may have been just completed when he left Rome. He abandoned work on the Fasti, possibly because of his exile – if he had stayed in Rome surely this poem would have been completed. He also wrote the short Remedia Amoris (Love’s Remedy) in c.AD 2. En route to his exile in Tomis he wrote the invective Ibis, viciously attacking an (anonymous) enemy (the enigmatic Ibis of the title).

Ovid appears to have been told that, as a condition of his exile, he was to remain in the vicinity of Tomis, located 100km from the mouth of the Danube on ‘the very edge’ of the Roman empire (Tristia 2.200). For all his complaints, Ovid seems to have obeyed this stricture faithfully. Technically, Tomis was located in what Rome called Moesia but what Ovid terms Pontus, Euxine Pontus or Left Pontus (meaning ‘on the left’ as you entered the Black Sea). He uses the term sinistra – which can mean both ‘left’ and ‘sinister’ (Tristia 5.10.14), a double meaning that fits his opinion of the place. Originally, the sea was called the Axenus (‘inhospitable’ – Pliny Natural History 4.12.76), but this was changed at some point to the more euphemistic Euxine (‘hospitable’) Sea; no doubt Ovid thought the original name a more appropriate one.

Augustus had pushed forward the conquest of the Lower Danube and had created an independent military command by AD 6 (the preafectura civitatum Moesiae et Treballiae), which commanded the territory of modern Serbia and north-western Bulgaria. The province of Moesia, with a garrison of two legions (V Macedonica and IV Scythica) was then established by AD 15 (during Ovid’s exile), stretching along the southern bank of the Danube from Singidunum (modern-day Belgrade, Serbia) to the mouth of the Yantra River on the Danube (at modern-day Krivina, Bulgaria).

Ovid’s poems written in exile contain much (derogatory) comment about the people(s) in and surrounding Tomis. In his time in exile, however, Ovid learned both the Getic and Sarmatian languages (Epistulae Ex Ponto 3.2.40) and even wrote a poem in Getic (4.13.18–19, Tristia 3.14.48), although at Tristia 5.11.36 he says he still must make himself understood by gestures. He observed (with exaggeration and poetic licence) that he lived among his enemies who poisoned their ‘every dart (spicula)’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.2.16) and that: ‘Equipped with these the horseman circles the frightened walls as a wolf runs about the fenced sheep. The light bow once bent with its horsehair string remains with its bonds ever unrelaxed. The roofs bristle with implanted arrows as if shrouded in a veil, and the gate scarce repels attack with sturdy bar’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.2.117–22).

Ovid’s picture of Getic horse archers is corroborated by both archaeology and the picture of Thucydides, four centuries earlier (2.96.1). This is not the picture of them you get from the Column of Trajan in Rome – there are Dacian cavalry and archers but they are rare and not the dominant types of troops. Ovid’s picture, however, is backed up by archaeological finds. The poet Horace, too, had said that the Dacians ‘are best known for their flying arrows’ (Odes 3.6.13-16). Dio Chrysostom paints almost the same picture (Discourse 12 16-20) observing ‘one could see everywhere swords, everywhere corselets, everywhere spears, and the whole place was crowded with horses, with arms, and with armed men’ (12.19).

Ovid paints an evocative picture of raids (and sieges) during his time in exile and, even allowing for poetic exaggeration, he was an eyewitness to these events so should be granted some authority (especially when his picture is reinforced by both archaeology and other eyewitnesses). The fact of common Dacian, Getic, Sarmatian, and other tribes’ raids across the Danube is one we find leading up to the wars of Domitian, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius and beyond. Many surviving accounts of such raids in the traditional historical record are dissatisfyingly brief indeed and, at most, we hear of a raid and its defeat (or not) without much more to go on. The surviving literary record of both Domitian’s and Trajan’s campaigns are poor indeed and we can use Ovid to augment what we know.

Ovid allows a larger, more detailed picture to be drawn or Roman life in the threatened border zone; one of almost perpetual anxiety over the proximity of armed enemies and the threat of imminent raids and their consequences. He also gives details of the limited defence able to be mounted by frontier communities with little (or no) assistance from legions stationed at their garrison forts in the province. This would seem to have been a reality of life on the edge of the empire; Ovid surmises that ‘even when peace prevails, there is timorous dread of war’ (Tristia 3.10.67). The reason for Domitian’s campaigns was to punish raids that had killed more than one commander in Moesia; Trajan’s seem to have been pre-emptive but also probably caused by the continuing (and growing) threat of more Dacian raids.

The spiculum mentioned by Ovid as the weapon of Rome’s enemies at Tomis was usually used to refer to a thrown javelin in Roman thinking although Ovid may use it in the sense of an arrow. They did use javelins too, however. No other source tells of the poisoned weapons of the Getae, Dacians or Sarmatians, but Ovid often repeats the claim (Epistulae Ex Ponto 3.1.26, 4.7.11–12, 4.7.36, 4.9.83, 4.10.31; Tristia 3.10.64, 4.1.77, 5.7.16). The archaeological record of Dacia corroborates the ubiquity of archery and horses recorded in Ovid – yet this is not emphasised in other (admittedly fragmentary) sources or on Roman monuments such as Trajan’s Column. Nevertheless, given how common horse accoutrements and arrowheads are in surviving graves in Dacia (Cioată 2010: 5, 11; one-third with horse trappings and more than 300 arrowheads), it is Ovid’s picture that is reinforced.

Ovid, writing in his fourth and fifth year in Tomis (so AD 12–14), tells us that he fought with ‘cold, with arrows, with my own fate’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.2.25–26), imagery that is repeated (1.7.9: ‘I should live midst ice and Scythian arrows’, 3.1.1–2: ‘land never free from cruel enemies and snows’). He talks of ‘constant strife while the quiver-bearing Getan rouses stern war’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.8.6), and that the threat of barbarian raids meant no soil could be tilled (Epistulae Ex Ponto 2.7.70, 2.8.69, 3.8.6, 3.9.4; Tristia 2.187).

Ovid talks of a treeless landscape and endless winter (at least for someone from central Italy – Ovid was from Sulmo, modern Sulmona, Abruzzo, Italy), where no fruit or grape grew, and no land was tilled. There were only ‘vast steppes which no man claims’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.3.55-56). At Tristia 5.10.23–26 Ovid describes the rarity of a man who ventured out to till the fields; he had to plough with one hand and hold a weapon in the other, shepherds needs must wear helmets, and blowing on their pipes warned, not of wolves threatening their flocks, but of an approaching warband. He talks of nightmares, dreaming of ‘avoiding Sarmatian arrows or offering a captive’s hands to cruel bonds’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.2.45-46). At Tristia 4.4.59 Ovid talks of the peoples around Tomis as ‘eager for plunder and bloodshed.’ This (accurately) suggests that such raids were commonplace and that the fear of being captured and sold into slavery were relatively constant (again, with licence for exaggeration and poetic overstatement). The regularity of raids mentioned in the sources (both Dacian and others’ across the Danube) into the 5th century at least suggest Ovid’s picture was not far from the truth. Ovid emphasises how remote he was in Tomis and he paints a picture of the fear and foreboding of other raids soon to come: ‘what other tribes, when cold halts the Hister’s flow, wind along the icy back of the stream on swift horses. The most of these people neither care for thee, fair Rome, nor fear Ausonian [Italian] soldiery. Bows and full quivers lend them courage, and horses capable of marches however lengthy and the knowledge how to endure for long both thirst and hunger, and that a pursuing enemy will have no water’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.2.79–86).

We can note again the emphasis on cavalry and archery in this account. Cavalry were probably an essential part of the raids launched across the Danube (Pogăciaş 2022: 47) and yet cavalry are not emphasised in Latin sources or on Roman monuments like the columns of Trajan or Marcus Aurelius (although they are present on the former).

Elsewhere, Ovid talks of ‘close at hand on the right and the left is a dreaded enemy terrifying us with imminent fear on both sides’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.3.57–58). On one side were the Bistonian spears (the Bistones were a Thracian people around Mount Rhodope in modern-day Bulgaria and who are here probably used to represent all those situated south of Tomis), and on the other side were the Sarmatian darts (spicula). Ovid also emphasises that he was ‘encircled about by Getic arms’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 2.8.69, 3.9.4; Tristia 2.187); there was ‘no side free from an enemy’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.7.14) and he was ‘surrounded by the clash of Getic arms’ (Tristia 5.3.11).

Ovid talks (perhaps exaggeratedly) of the appearance of the tribesmen who surrounded him. Again, we should take this view with some poetic salt and as that of a somewhat effete and cultured Roman: they were ‘filthy’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.2.106), ‘stern’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.5.12, Tristia 5.1.46), ‘shaggy’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.5.74, 3.5.6), ‘unshorn’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 4.2.2), ‘fierce’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.7.2, 2.1.66), ‘wild’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 1.7.12, 1.8.16, 3.4.92, 3.9.32, 4.15.40), ‘uncivilized’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 3.5.28; Tristia 5.3.8), ‘barely pacified’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 2.7.2, Tristia 5.7.12), the ‘grimmest race’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 2.7.31), ‘clad in skins’ (Epistulae Ex Ponto 4.10.2), ‘hostile’ (Tristia 3.14.42), a ‘trousered throng’ (Tristia 4.6.47), ‘quiver-bearing’ (Tristia 4.10.110), and ‘Mars-worshipping’ (Tristia 5.3.22). These (distasteful) observations remain consistent for the whole of his exile, even after he had learned the local language and written a poem in it. Ovid notes that barbarian clothes consist of skins and ‘stitched breeches’ (Tristia 3.10.19), which ‘keep out the evils of the cold; of the whole body only the face is exposed. Often their hair tinkles with hanging ice and their beards glisten white with the mantle of frost’ (Tristia 3.10.20-22). The Dacians did have trousers of fabric but we have no skins – men are shown with tunics, cloaks or bare-chested.

Ovid exaggerates when he says that snow would remain unmelted for two years (Tristia 3.10.16) but, compared to the climate of central Italy, the cold of Tomis must have been a huge shock. He does, however, write of spring there (Tristia 3.12) and later admits that in his ten years there the Danube only froze over three times (Tristia 5.10.3–4).

Other details are useful too: that the Danube is as wide as the Nile (Tristia 3.10.27) and that when the Danube froze, ‘the barbarian enemy with his swift horses rides to the attack’ (Tristia 3.10.54). Again, we know this to have been the tactic and practice of the tribes over the Danube at least into the 2nd century AD and beyond. Again, here, Ovid calls them ‘an enemy strong in steed and in far flying arrows’ (Tristia 3.10.55). Ovid’s details here and elsewhere make it almost certain that he witnessed raids, people fleeing for refuge, and others bound and led into captivity. These were the tactics of the Dacians until they were conquered by Trajan in 106 (and even after that). Again, Ovid mentions poisoned arrows (Tristia 3.10.64) and that what cannot be taken is destroyed.

We can also note that, strategically, luring a pursuing enemy into unfamiliar territory and land where there was no water was something the tribes on the northern bank of the Danube would continue to do until the reign of Marcus Aurelius at least (the battle on the frozen Danube and the Miracle of the rain fought in Marcus’ wars in the 170s reflect both tactics – Dio Cassius 71/72.7, 8–10 and 13–14).

In a letter to king Cotys III (r. AD 12–18), a Thracian client king of Rome (Epistulae Ex Ponto 2.9), Ovid talks again of training in horsemanship and of hurling the javelin (iaculum – perhaps meaning from horseback – 2.9.57–58). Cavalry are again emphasised at 3.1.8; he lived in a place ‘ever trodden by the swift horses of a neighbouring foe’, and archery at 3.5.45 and 4.3.51-52. Ovid even sent one of his correspondents a full Scythian quiver (3.8.19-24), calling arrows the ‘pens’ of the land (and blood was its ink).

Ovid recounts a local campaign he had heard tell of although he was not a witness (Epistulae Ex Ponto 4.7), which was conducted by a senior centurion of a legion, the primus pilus Iulius Vestalis, to retake the town of Aegisos (Aegyssus – modern Tulcea, Romania) which had been seized by the Getae. Although this account is delivered in terms of epic poetry and in a letter addressed to Vestalis himself, its details have verisimilitude. Its details have, however, been entirely brought into doubt (Williams 1994: 41) though without good reason. He once again mentions the cold – the wine is frozen (‘standing rigid with frost’) just as the Pontus is (4.7–8) and a Iazygian tribesman leads his wagon over the frozen Hister (4.9–10). Vestalis witnesses poison ‘hurled on the barbed steel’ so that ‘the missile possesses two causes of death’ (4.11–12). The Romans, coming down the Danube, advanced their standards (signa) against the Getae (4.7.27–28) and charged the enemy steel and the hill (4.7.33–34). There is a hill that commands the site at Tulcea (and which was the site of a later Roman fort).

This detail supports the accuracy of the report (Helzle 2005 – the author travelled to Tulcea to investigate Ovid’s claims) although it may have been an open battle (the hill is seized rather than town attacked in Ovid suggesting the Getae positioned themselves uphill – another common tactic). The steel (ferrumque) braved by the Romans may, therefore, mean the Getan falces of their infantry rather than cavalry. The Getae defended themselves with stones ‘greater in number than winter’s hail’ (4.7.34-5), (poisoned) missiles (iaculorum, meaning javelins), and arrows (though he, again, here uses spicula – ‘arrows with painted feathers cling to your helmet, scarce any part of your shield lacks a wound’ 4.7.37–38). Vestalis was wounded (4.40), but his love of glory was greater than the pain. The two sides then closed and the battle was fought hand-to-hand (dextera dextrae) ‘at close quarters with the fierce sword’ (fero potuit commius ense geri – ensis is a generic term for sword). This, too, was the typical Roman tactic of closing hand-to-hand with swords once missile exchange had occurred and any enemy missiles braved in closing the gap between the two front lines. The remaining soldiers were inspired by the bravery of their centurion and many Getae fell. The town was retaken. These details are entirely credible.

In Epistulae Ex Ponto 4.9, Ovid recounts that Lucius Pomponius Flaccus commanded the southern banks of the Danube and ‘cowed with his sword (ense) the Getae who trust in the bow (arcu)’ (4.9.78 – hic arcu fisos terruit ense Getas). Flaccus was possibly prefect of the preafectura civitatum Moesiae et Treballiae (he was later consul in 17 and, later that year made governor of the (new) province of Moesia). It is also possible he was a legatus to Gaius Poppaeus Sabinus, the earlier governor. The contrast of Roman sword with Getae/Dacian arrow in this line may be a poetic hendiadys of the two styles of fighting, Roman and Getic, although it is a paring usually made of Roman pilum against the Persian sagitta (arrow) – this imagery goes back to Aeschylus’ use of the Greek dory (spear) contending against the Persian bow (toxon – Persae 85-6, 147–49); imagery later adopted by Latin authors for the plentiful Roman conflicts against the Parthians and Persians (see Diogenes, Laertius 5.5; Festus, Breviarium 15). In his poem, Ovid contends that his tales of exile and the land thereabouts, of the climate and the water freezing for acres, of the ‘foe so close at hand’ (4.9.82) and slender arrows dipped in poison (4.9.83) could all be verified by Flaccus. He also makes a point that is verified by several scenes on Trajan’s Column – Flaccus could also confirm ‘whether the human head becomes a hideous offering’ (4.9.84).

As an exile, Ovid admitted that he had shunned military service as a young man in Rome. Now, however, he served as a guard (custos) in Tomis: ‘now that I am growing old I fit a sword to my side, a shield to my left arm, and I place a helmet on my grey head. For when the guard from the lookout has given the signal of a raid, forthwith I don my armour with shaking hands. The foe with his bows and with arrows dipped in poison [arcus imbutaque tela venenis] fiercely circles the walls upon his panting steed’ (Tristia 4.1.73-78). Again we can note the combination of cavalry, archery (and poison).

This is one of the few accounts in all of Roman history of a town guard in action and these circumstances must have been similar to many communities without a proper garrison when they were faced with a raiding Dacian tribe or any invading force. We hear of the vigiles (Night Watch) and cohortes urbanae (Urban Cohorts) of Rome, but each community probably had similar units organized as a militia though proportionately smaller. Often, we are told of forts and towns overrun by Dacian, Germanic or later Gothic raids, but Ovid’s account makes it seem more real. Those who could not find shelter in time were made captive or died, struck by a poisoned arrow shaft. We can note that it was only after the raid was signalled that armour was donned – watch was otherwise kept with helmet and shield but no armour.

In a poem addressed to his (third) wife, Fabia (Tristia 5.7), Ovid tells her ‘what the people of the land of Tomis are like’ (5.7.9). He describes them as a mix of Greeks and ‘scarcely pacified’ Getae: ‘Greater hordes of Sarmatae and Getae go and come upon their horses along the roads. Among them there is not one who does not bear quiver and bow (arcum telaque), and darts yellow with viper’s gall’ (5.7.13–16). He calls the Getae ‘veritable pictures of Mars’ (5.7.17 verissima Martis imago) although some MSS. read ‘mortis’ at this point (verissima mortis imago): ‘veritable pictures of Death’ – both, no doubt, would have been considered an appropriate description by Ovid. He goes on to call their voices harsh, their countenances grim, ‘neither hair nor beard trimmed by any hand, right hands not slow to stab and wound with the knife [cultro] which every barbarian wears fastened to his side’ (5.7.18-20). This does seem to match the images of Dacians on Trajan’s Column and other monuments and the ubiquity of the small curved sica blade we see in archaeology. Peculiarly, Ovid calls them cultros – only Valerius Maximus, writing in the reign of Tiberius (r. AD 14–37), (Memorable Deeds and Sayings 3.2.12) uses the term sica relating the death of Publius Licinius Crassus Dives Mucianus in 130 BC at the hands of a Thracian. Later in the same poem, Ovid complains that no one speaks Latin and even those who speak Greek do so with a ‘Getic twang’ (5.7.51). He laments that life among them was robbing him of his own knowledge and memory of Latin and, since they did not speak the language, nor could they appreciate Ovid’s art and poetic genius. He talks of the land as ‘devoid of charm’ (5.7.43) and ‘if I look upon the men, they are scarce men worthy of the name; they have more of cruel savagery than wolves. They fear not laws; right gives way to force, and justice lies conquered beneath the aggressive sword (ense). With skins and loose breeches they keep off the evils of the cold; their shaggy faces are protected with long locks’ (5.7.45–50). Again, trousers seems accurate but not skins, and long hair and beards were typically worn.

We can note once more, that although these terms are couched in thorough negativity and with poetic exaggeration from the Roman perspective, they are the best description we have of the appearance of the Getae and Dacians. What is more, to once more answer the criticism that this was a fictional exile, the description Ovid provides matches the archaeological record as far as we can tell. We can see Ovid’s description matching how Dacians are depicted on Trajan’s and Marcus Aurelius’ column and other monuments such as the Trajanic statues preserved on Constantine’s Arch and those now in the Vatican – all of them post-dating Ovid’s description and we do not know how prevalent such peoples were as subjects of Roman art in Ovid’s time or before. We do not know if skins were worn or not, it is possible they were and that the surviving artistic depictions simply did not present them in that way.

In one of the last poems in the Tristia (5.10), Ovid compares his own exile to the length of the Greek siege of Troy – ten years. In his tenth year of exile (so AD 17/18), his picture is the same as it ever was: ‘Countless tribes around about threaten cruel war, thinking it base to live if not by plunder’ (5.10.15-16). He goes on: ‘Without, nothing is secure: the hill itself is defended by meagre walls and by its skilful site’ (5.10.17–18). This description of a hill with meagre walls matches the archaeology of the site of Tomis. Ovid continues: ‘When least expected, like birds, the foe swarms upon us and when scarce well seen is already driving off the booty. Often within the walls when the gates are closed, we gather deadly missiles (noxia tela) in the midst of the streets’ (Tristia 5.10.19–22). Here, and in other passages, the unexpected arrival of the Dacians is mentioned. This too is a trait of any raiding civilization – we find the shock of their arrival mentioned in sources down to the 5th century.

Ovid tells us that ‘Scarce with the fortress’ (castelli) aid are we defended; and even within that the barbarous mob mingled with the Greeks inspires fear’ (Tristia 5.10.27–28). This (probably) accurately reflects the circumstances of having tribesmen of the enemy without living inside the walls of the town of Tomis. Ovid describes that more than half of the population of Tomis was barbarian who were (and would remain) indistinguishable from one another to Roman eyes; potential traitors would have seemed to be everywhere, the anxiety of which Ovid’s verses reflect elsewhere. The small help provided by the local fort and its garrison (who probably had troubles of their own) is also interesting for Ovid’s time and later invasions – during a raid they would have had a hard enough time defending themselves to be able to spare troops to send elsewhere even in the immediate vicinity to aid in towns’ defences.

There is much worthwhile material for the military historian of the Dacian Wars in the poems of Ovid’s Tristia and Epistulae Ex Ponto, painting a vivid (and accurate) picture of Getic, Dacian and Sarmatian raids – both in terms of how they were delivered and how they were anticipated and received. On the appearance and arms of such tribesmen, Ovid counts as one of the best literary sources we possess. The military historian can therefore confidently add their voice to calls for Ovid’s exile to be taken, if not at face value due to its poetic nature, then at least as a reliable eyewitness record of an actual exile on the edge of the Roman empire in the early 1st century AD. Moreover, it is one that provides us with a great deal of useful information for the Dacian campaigns later in the century.

You can read more in Roman Soldier vs Dacian Warrior: Dacian Wars AD 85–106

Further reading

Cioată, D. (2010). Warriors and Weapons in Dacia in the 2nd BC-1st AD Centuries. PhD Thesis, Babeş-Bolyai University, Romania. Cluj-Napoca: Babeş-Bolyai University.

Compton, T.M. (2006). Victim of the Muses: Poet as Scapegoat, Warrior and Hero in Greco-Roman and Indo-European Myth and History. Hellenic Studies Series 11. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. Available at https://chs.harvard.edu/chapter/part-iii-rome-23-ovid-practicing-the-studium-fatale/#n.6

Claassen J.-M. (1986). Poeta, Exsul, Vates: A Stylistic and Literary Analysis of Ovid’s Tristia and Epistolae ex Ponto. Dissertation (Stellenbosch, South Africa).

Claassen, J.-M. (1999). ‘The Vocabulary of Exile in Ovid's Tristia and Epistolae ex Ponto’ Glotta 75.3–4: 134–71.

Fitton Brown, A.D. (1985). ‘The unreality of Ovid’s Tomitian Exile’, Liverpool Classical Monthly 10: 18–22.

Goold, G.P. (1983). ‘The Cause of Ovid's Exile’, Illinois Classical Studies 8: 94–107.

Grebe, S. (2010). ‘Why Did Ovid Associate His Exile with a Living Death?’ Classical World 103: 491–509.

Green, Peter (ed.) (2005). Ovid, The poems of exile: Tristia and the Black Sea letters. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hardie, P. (2002). ‘The Exile Poetry’: Ovid’s Poetics of Illusion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Helzle, M. (2005) ‘Epic and History in Ovid Pont. IV 7’, paper presented at CAMWS, 31 March 2005, Northwestern State University (abstract available at https://camws.org/meeting/2005/abstracts2005/helzle.html).

Ingleheart, J. (ed.). (2011). Two Thousand Years of Solitude: Exile after Ovid. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McGowan, M. (2009). Ovid in Exile: Power and Poetic Redress in the Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto. Mnemosyne Suppl. 309. Leiden: Brill.

Myers, K.S. (2014). ‘Ovid’s Self-Reception in his Exile Poetry’ in John F. Miller & Carole E. Newlands (eds), A Handbook to the Reception of Ovid. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell: 8–21.

Pogăciaş, A. (2022). ‘Raids across the Danube. The impact of the Getae and Dacians’, Ancient Warfare Magazine 16.1: 46–49.

Richmond, J. (1995). ‘The Latter Days of a Love Poet: Ovid in Exile’, Classics Ireland 2: 97–120.

Rosenmeyer, P. (1997). ‘Ovid’s Heroides and Tristia: Voices from Exile’, Ramus 26: 29–56.

Syme, R. (1978). History in Ovid. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Thibault, John C. 1964. The Mystery of Ovid’s Exile. Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Williams, G.D. (1994). Banished Voices: Readings in Ovid’s Exile Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, G.D. (2002). ‘Ovid’s Exilic Poetry: Worlds Apart.’ In Barbara Weiden Boyd (ed.), Brill’s Companion to Ovid. Leiden: Brill: 337–81.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment