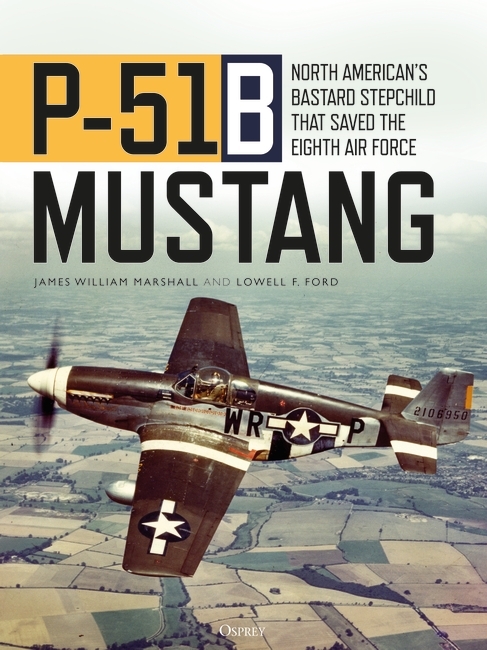

On the blog today, Bill Marshall, one of the authors of the fascinating study P-51B Mustang discusses the inspiration behind his new release.

I was asked by Osprey to answer the fundamental question: “How did you become an author?” or “How did your interest in World War II aviation lead you to write about it?” Thinking about the questions led me to consider the most important influence in my life – my father, Bert Wilder Marshall, Jr.

My earliest memory of him was perhaps at the age of three, when my father was squadron commander of the 318th Night Fighter Squadron – equipped with P-61Bs – post-World War II at Hamilton Field. My first real memory of an aircraft was his crew chief lifting me up to my dad, who put me in the right seat of a P-61. This was in 1948, just before dad became wing commander of the 35th Fighter Group based at Johnson Air Force Base in Japan.

My first exposure to the Mustang was my father putting me in the cockpit, where I had to stand to look through the gunsight. As an Air Force “brat,” our family was on a perpetual Odyssey from base to base, assignment to assignment, but most of the assignments were at bases where the noise of the flightline never ceased.

My love for aircraft, fighters, and World War II history had one common denominator – my father. My mother was also an enormous influence and she taught me to read at a very early age. My first books were Target: Germany, First of the Many, and Battle of Britain, and I devoured the books in our library that were related to World War II and specifically the war’s European Theater of Operations – as well as the history of air power from the beginning of the 20th century.

Let me introduce you to my father. He was born in 1918, the second oldest son of Bert and Nell Marshall, in Royse City, Texas. Like many other families during the Depression, the Marshall family was poor. All the sons spent their childhood days working from an early age to help support the family. All the boys excelled at football and track. My father was unique, being gifted both academically and as an athlete. He was a three-time Texas All State tailback and a future member of the Texas High School Hall of Fame.

He went on to become a star tailback quarterback at Vanderbilt University and was selected to Colliers All America Honorable Mention. Following graduation in 1940, he joined the US Army Air Force as an aviation cadet and was selected as an instructor. For three years he toiled in Training Command, trying to get into combat by volunteering for the American Volunteer Group and other combat assignments, until he finally escaped when he was assigned to a B-26 Marauder squadron training at MacDill Airfield that was due to ship out in late 1943. From there he managed to get a reassignment to fighters. He jokingly said he was able to do so by claiming he was too short to reach the rudder pedals on the B-26.

After flying P-40Ks at advanced fighter training in Sarasota, Florida, he was reassigned as a replacement fighter pilot in the European Theater of Operations in mid-May 1944. His very good friend Lt Col Claiborne Kinnard, squadron commander of the 354th Fighter Squadron (FS), 355th Fighter Group (FG), saw his name on the new replacement list and had him assigned to the 355th. As a brand-new Mustang pilot with only three hours’ flight time following his transition from the P-40 in Sarasota, Bert Marshall shot down his first German aircraft (a Ju 87 Stuka) on his first day of combat, June 6, 1944.

Ace 354 Marshall climbing in JaneVII

(Author Collection)

Two weeks later he shot down two Bf 109s off other pilots’ tails. He quickly rose from element to flight leader, and then he was promoted to become the 354th FS’s operations officer at the end of June. He got two more kills on July 28 and August 6 to become the fastest ace (both in respect to the time taken from first mission to “making ace” and the fewest missions flown to claim five victories) in the 355th FG. At the same time, he was promoted again to become the 354th FS’s commanding officer as a captain. Six weeks later, he was shot down by German anti-aircraft fire near Saint Étienne, France, and was saved by Lt Royce Priest in the first “piggyback” rescue in a P-51 Mustang in the US Army Air Force. He was promoted to major later that same day.

During September, he destroyed two more Bf 109s and was fighter commander of the escort for the last shuttle mission to Russia–Italy–England. On September 18, the bombers dropped supplies to the Polish underground trapped by German forces in Warsaw, then proceeded to Mirgorad and Poltava as the 355th FG landed at Piryatin, Ukraine. On the 19th, Marshall escorted the bombers attacking Szolnok and proceeded to Foggia, Italy. On the 22nd, the 355th FG completed the third leg to Steeple Morden.

On October 3, his deputy, Maj Chuck Lenfest, became stuck in the mud after landing in a bid to rescue the 355th FG’s top ace, Capt Henry Brown – both men were captured. The loss of his deputy, combined with his recent promotion to deputy group commander, mandated that Marshall also still commanded the 354th FS, until his replacement was named in late October. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel at the same time, rising from captain in mid-August to lieutenant colonel in approximately eight weeks.

Following the last mission of his first tour, he returned home for 60 days before heading back to Britain with the new CO of the 355th FG, “Clay” Kinnard. Following VE Day, Bert Marshall became group commander, and he returned home in October 1945.

355fg WRBbar Colour

(Author Collection)

As an example of my father’s modesty, I was never aware of his combat record, except that I knew he was an ace. Following his death in 1979 due to an aneurysm, I decided to collect all the scrapbooks from both high school and World War II that his mother had carefully kept. Among them were many photos sent home by my father. The initial purpose was to protect his legacy for my sons and daughters.

I contacted several of his close friends who flew with him during World War II, including pilots, crew chiefs, and ground officers, to obtain more images that they had of him. I was overwhelmed by a flood of scrapbooks and data, and decided to research more of his history with the 355th. It was then that I understood that I had enough information to perhaps write a squadron history. From there I collected information on the group itself from the US Air Force Historical Research Center. The decision to write a book about my father’s service with the 355th led me to write a book about all the squadrons and records of the 355th FG as a legacy for his grandsons and granddaughters and future “Marshalls.”

Along with my great respect for all the warriors who flew in combat in fighters and bombers during World War II, I acquired the love for both the B-17 and the P-51 Mustang. I suppose this also contributed to me acquiring degrees in aero engineering and subsequently entering the workforce as an engineer. So perhaps another question – “Why co-author P-51B Mustang: North American’s Bastard Stepchild that Saved the Eighth Air Force?”

Over many years I collected much information regarding the development of the Mustang by North American Aviation, but I found that none of it satisfactorily answered the really important questions, such as, “Why was it so long before the USAAF accepted the Mustang?” or “Why didn’t the USAAF encourage NAA to compete in pursuit fighter development before 1942?” or “Could the P-51B have been delivered for long range escort much earlier?” or “What was the real story of the development of the fuselage fuel tank and bubble canopy?” Several excellent authors (Robert Gruenhagen, Ray Wagner and Paul Ludwig) all had insights as to various aspects, but not the detail I was looking for. This led to further contact with significant authors (Gruenhagen and Wagner), and with leaders at North American Aviation, including Ed Horkey, Edgar Schmued, and Bob Chilton, when we lived in Los Angeles. The great Mustang researcher and author Bob Gruenhagen engaged in years-long e-mail correspondence with me, which further illuminated the path of further research. From my contacts with the North American Retirement Group, I met another great researcher and article writer, Lowell Ford.

Lowell had saved so many critical NAA source documents and so much information that Rockwell had been going to destroy as “unessential” following its acquisition of North American Aviation. Lowell’s trust in me led to a great exchange of information and history in respect to the development of North American Aviation’s entry into pursuit aircraft. Together, we assembled the details, and it was from this association and supply of critical source documents that we agreed to jointly tell the story of how close events and blunders could have prevented the supply of the great Rolls-Royce-powered P-51B Mustang just in time to save many lives in the great battles over Germany prior to D-Day.

P-51B Mustang is out now! Get your copy here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment