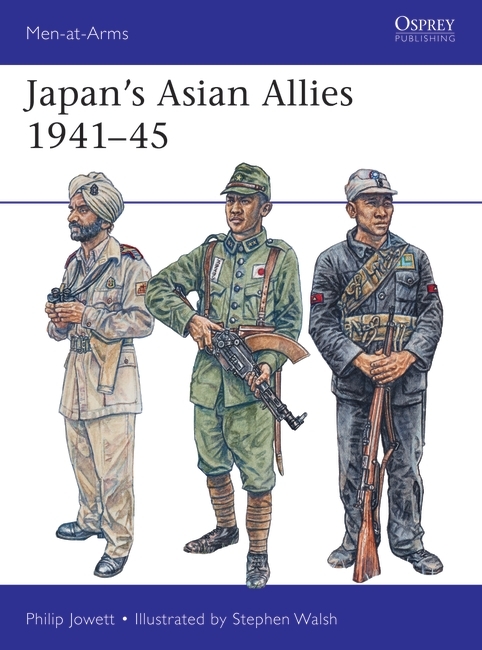

During the Japanese occupation of large parts of Asia and the Pacific in 1941-45, Japan raised significant numbers of troops to fight alongside them, as well as militias to guard their conquests. On the blog today, Philip Jowett, author of the upcoming Men-at-Arms title Japan's Asian Allies 1941–45 looks at these different volunteer groups.

Most military students are aware of Nazi Germany’s often reluctant use of foreign volunteers on the Eastern Front between 1941 and 1945. As the war turned against the Germans in 1942 – 43, their racist policy of not recruiting any volunteers who did not meet their strict Arian criteria were gradually relaxed. The Russian and other Slavic volunteers who were often fervently anti-Communist that had been rejected by German recruiters in 1941 were now accepted into military service. While the use of foreign volunteers by the German Army and in particular their Waffen SS is well documented, a similar policy by Imperial Japan is not as well known. The Japanese Imperial Armed Forces use of foreign volunteers during the Second World War is a largely ignored and yet significant aspect of the conflict.

Japan’s runaway victories in South-East Asia and the Pacific in 1941 – 42 ended with the Empire gaining control of the former colonial possessions of Britain and the Netherlands. In addition, Japan gained control of the US dominated Philippines whose government was on the road to a staged independence when it fell. These territories were soon added to Japan’s ‘Greater East Asia co-Prosperity Sphere’ an organisation set up supposedly to return ‘Asia to the Asians!’. In reality the peoples of Malaya, Burma and the Philippines were ridding themselves of one colonial master only to have them replaced by another.

Japan had begun to build its Empire since the late 1800s and by 1910 it had gained control of parts of China, and all of Korea and the island of Formosa. In 1931 the Chinese Northern of Manchuria were invaded by the Japanese and by 1932 had become a ‘client’ or ‘puppet’ state under the name of Manchukuo. In 1934 the deposed last Emperor of Imperial China was installed as Pu Yi, the ruler of the brand new Empire of Manchukuo. By 1941 the Armed forces of Manchukuo had an army with strength of over 100,000 men and a small Air Force and Navy. Not satisfied with the control of Manchuria, the Japanese spent the 1930s setting up local governments in Northern China and raising small ‘puppet’ armies to control them. In July 1937 any pretence that their ambitions did not include taking over all of China was ended when full-scale war broke out. Within a year the Japanese had conquered all of Northern China, Inner Mongolia and Central China and had set up several local ‘client’ governments The Provisional Government in Peking had 5,000 puppet soldiers, and the Reformed Government in Nanking had about the same number of poorly trained troops. In 1940 a Reorganised Government was formed in Nanking which incorporated all the other local ‘puppet’ governments. This new government was led by a high profile politician Wang Ching-wei who was a political rival of the Nationalist Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek. Under Wang’s leadership the pro-Japanese government raised an army of at least 300,000 troops and were provided by the Japanese with a few tanks and artillery pieces. These soldiers were nearly all ex-Nationalist troops who had deserted by the thousand with their officers to join the puppet army.

Soldiers of the Reformed Government Army based in Nanking stand on parade in 1938 dressed in a motley collection of uniforms. They are armed with captured Chinese weapons donated to them by the Japanese who supported the ‘puppet’ government. The setting up of various client governments in China by the Japanese was usually accompanied by the raising of a small army manned by desperate men like these.

After its relative success in raising local volunteers in mainland China in the 1930s, the Japanese looked to their newly won Empire to raise forces to help it rule. Japanese intelligence agencies had been working for years to try and exploit the weaknesses in the European Empires in Asia. When they were victorious in 1942, the Japanese began to work on the politicians and nationalists in the new territories to help them raise volunteer armies in every corner of their Empire. Promises of independence were handed out in some territories like Burma and the Philippines while ethnic conflicts were used in others to turn one group against another. Whatever it took, the Japanese were ready to persuade the peoples of Asia to join them in keeping the ‘hated’ Imperial powers from ever returning to Asia.

The Burmese were the first South-Eastern Asian group to fight for the Japanese with a small ‘Burmese Independence Army’ invading Burma along with the Imperial Army in 1941 – 42. A 30 strong cadre had been secretly trained by the Japanese on the Chinese island of Hainan in the weeks before December 1941. Beginning with about 1,000 men the BIA grew into a large unwieldy force of 200,000 unruly volunteers who were little better than bandits. Japanese officials swiftly reduced the BIA down into a 10,000 strong Burmese Defence Army which included the best volunteers of the earlier force. In 1943 when Burma gained its notional independence the BDA was turned into the Burmese National Army with strength of 15,000 men. Japanese officials did not trust any of their foreign volunteers 100% and neither of the Burmese Nationalist Armies were trusted to fight beside them in battle.

Volunteers of the Burmese Defence Army march through Rangoon in their Japanese style uniforms and bearing no arms. The BDA did receive Arisaka and Lee Enfield rifles as well as some Japanese light machine guns but little else. Although the Burmese leader, Aung San, asked for tanks and fighter aircraft from the Japanese for his men their promises of future weaponry never materialized.

Japanese agents had been looking to exploit the growing Indian nationalism and saw the opportunity to destabilise the most important part of the British Empire in Asia. They had kept an eye on the British Indian Army and planned to use ‘agent provocateurs’ in the coming conflict against Britain. During the Malaya Campaign, Indian volunteers worked to try and bring Indian troops fighting for Britain there over to the Japanese side. At the end of the Malayan campaign, turncoat Indian soldiers also entered prisoner of war camps to persuade their former comrades to join them in an Indian National Army. The Indian National Army which was recruited from the ranks of the 50,000 ex-soldiers of the British Indian Army captured in Malaya and Singapore. Some Indian troops were more than willing to fight for the Japanese in the cause of Indian Independence while others agreed to join the INA in the hope of escape back to Allied service. 40,000 men did volunteer and were armed with the worn out rifles, machine guns, artillery and armoured vehicles abandoned by the British Army at Singapore in 1942. These were taken into battle with the Indian National Army when it took part in the Japanese offensive to capture Imphal in the Summer of 1944. The whole offensive was a disaster for the Japanese and of course for the Indian National Army who lost thousands of its men in the Burmese jungle.

The Philippines was granted independence of a sort under the Japanese in 1943 and had an armed Constabulary to protect its ‘puppet’ leaders. During 1943 – 1945 this armed police force never reached its projected size of 40,000 due to its unpopularity with the Filipino population. The constabulary was joined by a number of small private armies which were lightly armed by the Japanese. In 1945 all the pro-Japanese groups were unified in the ‘Makapili’ organisation with about 5,000 volunteers armed by the Imperial Army. Given ex-US Army rifles and machine guns, the Makapili collaborated with the Japanese in the closing stages of the fighting and many died in the jungle rather than surrender.

Indonesia was the biggest problem for the Japanese with little chance of them being able to garrison its 1,700 far flung islands. It was divided into several parts by the Japanese with the two largest islands under the control of different Japanese Armies. Sumatra was united with Malaya under the control of the 25th Army while the largest island Java was under the 16th Army. The 16th Army began to raise a number of volunteer groups beginning with the Seinendan – Youth Column which was formed in August 1943. It was made up of 600,000 unarmed volunteers who paraded with wooden rifles and bamboo spears. Another mass organisation, the Keibodan – ‘Vigilance Corps’ saw the majority of the younger adult population of 1,300,000 signed up. Also in 1943 the PETA was raised as an armed force with 38,870 men on Java and another 960 on the nearby island of Bali. Another group, the Hei-ho was recruited as auxiliary helpers for the 16th Army and reached a strength of 25,000. Although unarmed the Hei-ho were trusted by the Japanese they served alongside and were given military training especially in the manning of anti-aircraft guns. On the island of Sumatra, a PETA type organisation was raised to perform the same role as its Javan counterpart and reached a strength of 9,000. A late addition to the many-armed groups in Indonesia was the Hizbollah a Muslim military organisation formed in1945. It was designed to exploit the popularity of the Islamic religion on the island but its 50,000 volunteers were armed only with bamboo spears.

Other smaller volunteer armies were raised in Malaya whose name was changed to Malai during the Japanese occupation. These included a regular 2,000 strong full time Giyugun and a 5,000 strong part-time, para-military force called the Giygutai. A Hei-ho type organisation, the 9,000 strong Gunpo worked as uniformed labourers for the Japanese Army. They received some military training from the Japanese but there was no real intention to use them as soldiers. Unlike other parts of the Japanese Empire, Malaya was never promised independence although pre-war nationalists were recruited to join the volunteer armies. The Malays were armed with ex-British Lee Enfield .303 rifles and Bren light machine guns and were pictured manning captured field guns. This was purely for the propaganda camera and Malays would never have been allowed to fire them in anger. On the island of Borneo there were also local volunteers known as the Kyodai who had 1,280 men with only a minority armed with Lee Enfield rifles. Other small units too numerous to list were set up on Pacific Islands under Japanese control and on some of the remote islands of Indonesia. New Guinea saw the raising of tribal volunteers by the Japanese and these came into conflict with other tribes who supported the Allies at the same time.

The various armed groups looked impressive on paper but in reality the lack of available arms meant that they were toothless. Small arms were in short supply and were handed out usually to the elite units of each volunteer army at best. Apart from the worn out weaponry of the INA and a few anti-aircraft guns of the PETA and Burmese National Army, there were no heavy weapons in service with Japan’s foreign volunteers.

Japan's Asian Allies 1941–45 on 25 June. Preorder your copy from the website now.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment