Michael McNally's recently published Campaign title, Dettingen 1743, analyses the battle of Dettingen, one of the major Allied victories of the War of the Austrian Succession, and the last time a British monarch commanded troops in the field. In today's blog post, Michael shares how this title came about.

Whilst the final manuscript for CAM 307 ‘Fontenoy 1745 – Cumberland’s bloody defeat’ was in the process of being published, my thoughts naturally turned to possibilities for my next project for Osprey. Originally the idea had been to revisit Marlborough’s campaigns and suggest a treatment of either Oudenarde or Malplaquet, but one aspect of Fontenoy which kept coming back to me was the incident where Lord Charles Hay of the British Foot Guards apparently chided the officers and men of the Gardes Francaises for their conduct at the Battle of Dettingen two years previously and, as 18th century battles go, it is quite well-known: King George II at the head of a British army marching towards the town of Hanau finds its path blocked by a French army near the village of Dettingen, and sweeps it aside in a hail of musketry before continuing on to its objective.

The thought continued to germinate, and in the summer of 2018 a friend of mine – Robert Hall – called me out of the blue to see if I would like to attend a talk on the Battle of Dettingen which was being given by Herr Helmut Winter, a local historian and authority on the battle. I didn’t need to be asked twice and, getting an early train from Cologne, I eventually arrived at Hanau where Robert picked me up and we drove to the Geschichtsmuseum at Karlstein am Main where the talk was taking place.

The next 90 minutes or so were fascinating, but all too brief, and afterwards we were not only able to talk to both Herr Winter and other members of the local historical society about the battle but also receive a guided tour of the small museum. The following day, a sculpture was to be unveiled where the Allied right flank had deployed and we were taken out to the site where we could see the eastern part of the battlefield.

The Field of Battle - with the exception of the area adjacent to the River Main, the battlefield was under crops which were due to be harvested later that summer.

Author's Collection.

By the time we headed back towards Robert’s house, I think the seed was beginning to blossom and so when I returned home, I immediately approached Marcus (Cowper) my editor at Osprey, with the suggestion that we ignore Marlborough and instead submit a proposal on George II. Marcus agreed that it would be a good subject to cover, and I drafted a series of notes roughly based around the following commonly held perceptions:

a) British overwhelming victory over the French.

b) The last time that a British king led his troops into battle.

c) The French inexplicably left a strong defensive position in order to attack the Pragmatic Army (British with Austrian and Hanoverian allies) but were broken by close-range musketry fire (as exemplified by the Gardes Francaises’ disastrous flight into the river Main).

d) Having brushed the enemy aside, the Pragmatic Army continued to its objective of Hanau.

Extract of contemporary French campaign map, showing the deplyoments around Dettingen. The Pragmatic Army can be clearly seen in a formation several liines deep.

Courtesy Helmut Winter/Franz Biller, Geschichtsverein Karlstein a.Main

In time, Marcus confirmed that we had got the green light and so I began my preparations.

The first stage of any project is to assemble the reference material and so I spent a few days trawling the internet for suitable images, and then assembled all of my ‘physical’ books on the period on a bookshelf next to my writing desk before copying all of my electronic texts onto a USB stick. Next I created a working folder with a separate document for each of the chapter headings before creating a bibliography from the relevant master file.

So, thousands and thousands of read pages and copious notes later, the end result will soon be in the shops, I personally feel that I now have a far better understanding of the battle than before. It was most certainly not the straightforward slogging match that many describe. Noailles’ meticulous plan – had it succeeded – had the potential to completely change the course of the war, not necessarily by capturing King George II, but by removing the Pragmatic Army (and thus a major expense for the British government) from the chessboard.

King George II at the Battle of Dettingen

Courtesy Helmut Winter/Franz Biller, Geschichtsverein Karlstein a.Main

Dettingen wasn’t an ‘infantry battle’ as has been described by many sources – the main action was in fact the cavalry combat on the west of the battlefield. It was the stubbornness of the British horsemen and the inability of the French to deploy their superior numbers that proved to be of pivotal importance and yet, with the exception of a few examples of individual gallantry, it is generally overlooked.

The central sector of the battlefield. The excessive woodland was planted during the nineteenth century.

Author's Collection.

I was also reminded of the care and thoroughness that one needs to exhibit when using and evaluating sources, especially contemporary ones. To give an example, some British sources of the period cite the capture of troops from the Régiment de Rouen and I spent a large amount of time trying to track down this unit that I could find no reference of elsewhere: there is no such unit in the French army of the period.

The answer, when I realised it, was simple. : the more recent of the British sources had obviously used the other as a reference, Rouen is pronounced Roo-On whereas the Regiment de Rohan (pronounced Row-On) was in the second line of the French centre.

So how do the points that I made in my original proposal relate to my final analysis of the battle? Well,

a) Dettingen wasn’t strictly speaking fought by Britain and France, in fact the two countries were not actually at war at this point in time, that would come later.

It is a testament to the confusion of coalition warfare that the forces defending the village were technically strictly speaking Bavarian, albeit in the form of French auxiliaries serving under their own officers and for their own objectives. On the other side of the Forchbach, they were faced by an Austrian army – which admittedly was indeed 1/3 Austrian – whose numbers were bolstered by a contracted force of Anglo-Hanoverian troops.

a) George II was indeed King of England, but at Dettingen he wore the uniform and insignia of a Hanoverian General Officer, which would lead to no end of political strife after the battle, so I would assume the point to be moot.

b) The French did indeed abandon their defensive positions in order to attack the Allies, but whilst Fortescue describes the Allied formation as being two lines of infantry, with the cavalry on the right of the line, Austrian and Hanoverian sources place almost all of the Allied cavalry on the left flank, with the various infantry brigades mixed up with each other. It should be noted that whilst Fortescue concedes the presence of one Austrian brigade, he fails to mention any Hanoverian troops.

c) The Allies did indeed reach their objective of Hanau, but at the cost of abandoning any attempt to push on into Bavaria as had been agreed. The story of King George dining on the battlefield to ‘show defiance’ to the enemy is, I’m afraid, untrue and any royal picnic would have taken place at the new camp around Hörstein. The reason for this is threefold: firstly there were still a significant number of fresh and well-supplied enemy troops to the army’s rear; secondly, Gramont’s retreat had now uncovered the French heavy artillery around Mainflingen, both of these factors being adequate reason to expedite the crossing of the Forchbach, but the final reason was that the Allies had already decided to abandon their casualties on the battlefield, requesting that the Duc de Noailles offer them the succour of his own medical facilities.

The River Main at Mainflingen. In 1743 the river would have been far shallower and considerably wider. The concealed French batteries would have been emplaced on the right of the image.

Author's Collection.

An Allied victory? Yes, but – in my opinion – only by the slightest of margins.

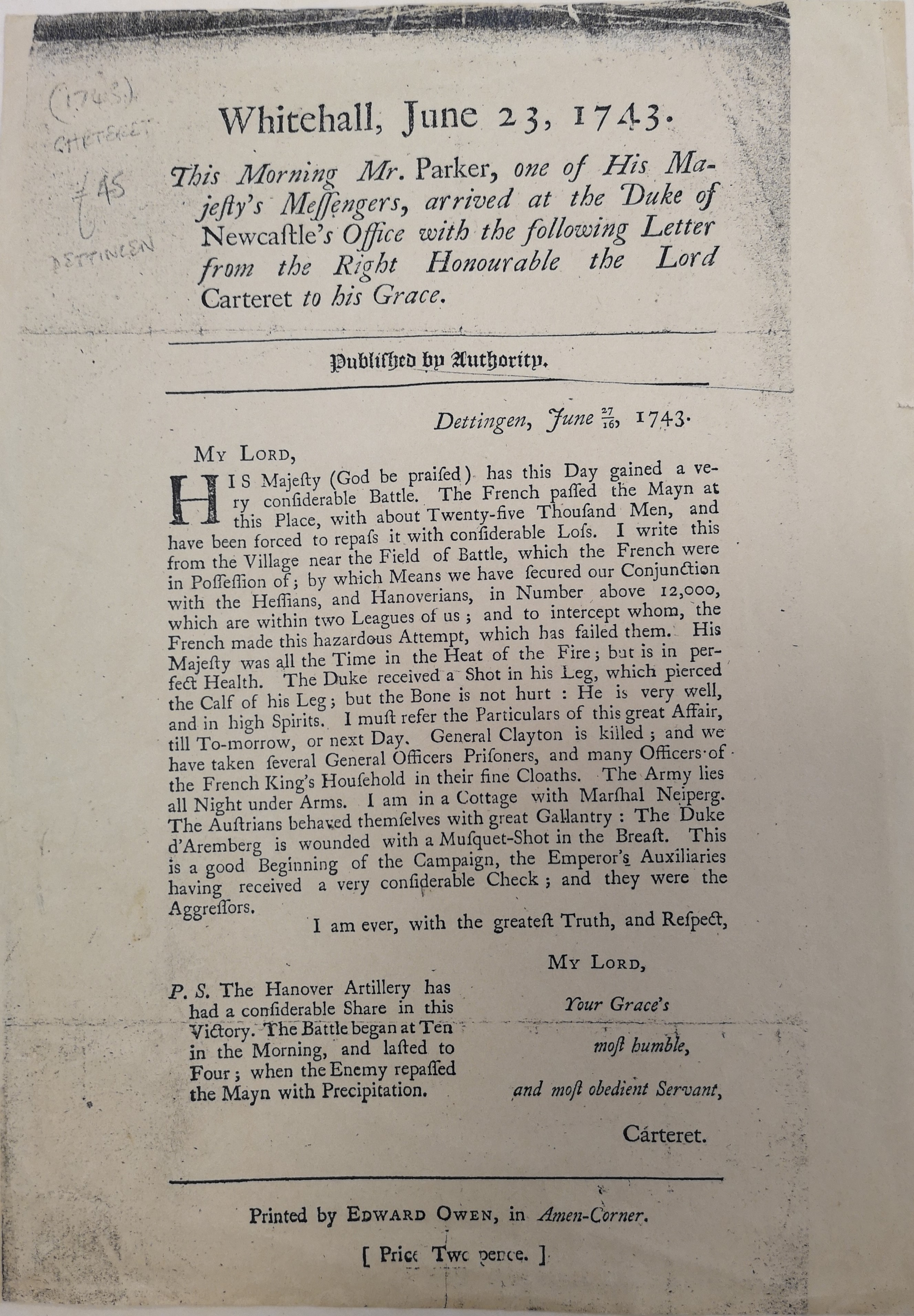

Lord Carteret's report on the battle as printed and sold in London. Note the reference to the French troops as 'The Emperor's Auxiliaries'.

Courtesy Helmut Winter/Franz Biller, Geschichtsverein Karlstein a.Main

Get your copy of Dettingen 1743 now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment