On the blog today, Si Sheppard looks at what might have happened had Constantinople fallen in 717 following the siege of Constantinople AD 717–18, the subject of his new book.

The world is witnessing plenty of history right now – politics, a pandemic, and panic on Wall Street – but March is turning out to be a very good month for alternate history, that is, speculation about what might have been different had an alternative path been chosen at a critical turning point in the past.

In the UK, the BBC released the mini series Noughts + Crosses, adapted from the young adult series of novels by Malorie Blackman, which takes place in a reality where the roles of colonizer and colonized have been reversed by the African conquest of Europe and the imposition of a racial hierarchy the mirror image of our own.

In the U.S., HBO is launching The Plot Against America, based on the bestselling book by Philip Roth. This takes, as its divergence from actual history, the election of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh as President in 1940 and the ensuing slow transition of the United States into an isolationist, quasi-fascist regime. HBO will be hoping to cash in on the success of Amazon’s successful series The Man in the High Castle, adapted from the novel by Philip K. Dick, in which Axis Powers have won World War II and divided the U.S. between them.

That these concepts have weight in the popular imagination is evidenced by the breadth and range of speculative fiction devoted to investigating their significance. For example, the brutal face of a Nazi Europe is also exposed in such works as Fatherland by Robert Harris, and SS-GB, by Len Deighton.

Other authors to explore the theme of a marginalized Europe include Kim Stanley Robinson in The Years of Rice and Salt, and Steven Barnes in Lion’s Blood. This fiction serves a useful purpose; to prick the bubble of complacency in the West that this is the best of all possible worlds, and that by definition, the ascendancy of Western culture was as inevitable as it is desirable. By depicting people of Western descent as without agency and reduced to the status of slaves, these texts force Western readers to empathize with the victims of Western imperialism.

Can we identify a critical juncture in the past that might have created such a reality? There is one entity in the historical record that had the potential to do so. Europe could never have been subsumed by the Persia of Xerxes or the Carthage of Hannibal or the Huns of Attila. But the Arab Caliphate forged by the heirs to the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th and 8th centuries came within a single ace of aborting the European efflorescence before it even began.

For hundreds of years, speculation about the limits of Islamic imperialism has centered on the Battle of Poitiers in 732, when the Merovingian warlord Charles Martel defeated an invading Arab host. In a famous phrase, Edward Gibbon illustrated the implications of an Arab victory:

A victorious line of march had been prolonged above a thousand miles from the Rock of Gibraltar to the banks of the Loire; the repetition of an equal space would have carried the Saracens to the confines of Poland and the Highlands of Scotland. The Rhine is not more impassable than the Nile or Euphrates, and the Arabian fleet might have sailed without a naval combat into the mouth of the Thames. Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.

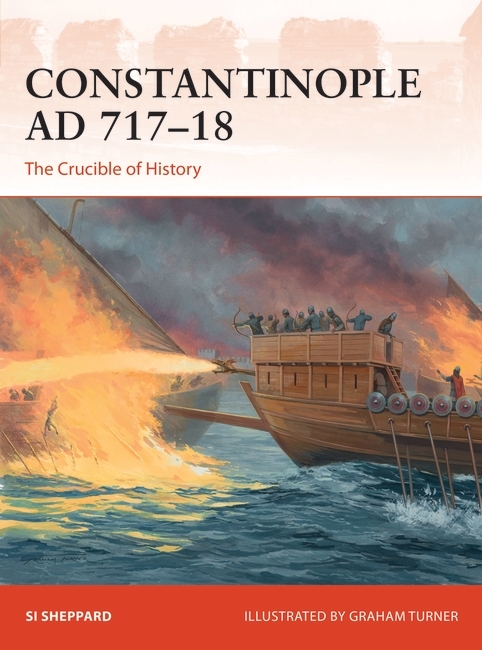

While the Frankish triumph was important in securing Europe’s less exposed western frontier, the supreme crisis had already played out on the much more vulnerable eastern flank, where the remnant of the Byzantine Empire was exposed to the full fury of the Umayyad Caliphs. Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, had already weathered multiple Arab assaults when it was subjected to a siege in 717 by the combined arms of the fully mobilized caliphal army and navy. Cut off from the outside world, Constantinople was left entirely to its own devices. Thanks to the superb construction of its peerless defensive walls, the stubborn courage of its garrison, the bold leadership of Emperor Leo III, the harsh winter weather, and the strategic deployment of legendary terror weapon Greek Fire, the city endured, and the siege was broken the following year.

But what if? Had Constantinople fallen, the Umayyad Caliphs would have styled themselves as the legitimate heirs to the Caesars, including the ancient demesne of Rome; they may even have advanced their banner from Damascus to the city of Constantine. In any event, their new neighbors, the Bulgars of the Danube, would have accepted Islam, just like the Bulgars of the Volga. With these new believers adding impetus to its momentum, within living memory of the Byzantine empire’s extinction the caliphate would have stretched from the Bosporus to the Baltic. The Ottoman penetration of Europe, eight hundred years later, wasn’t stopped until it was at the gates of Vienna, and the Sublime Porte had to fight its way through the centralized states of the Balkans and at least two crusades in the process; no such capacity for organized resistance existed in the 8th Century. One way or another, the pagan tribes of the Slavs, the Magyars, the Lithuanians, perhaps even the Scandinavians, would have been absorbed into the Dar-al-Islam.

The consummation of this process is not difficult to imagine. With Anatolia and the Aegean under Arab control at one end of the Mediterranean, and al-Andalus at the other, the next logical step would have been to close the circuit by taking Italy. Coordinated caliphal columns converging from east and west by land, complemented with unchallenged Arab naval superiority, would have overwhelmed whatever resistance the Lombards, the Papacy, and any remaining Byzantine enclaves could have offered. The Mediterranean would thus have become an Arab lake.

The incorporation of Rome into the caliphate would have driven the Papacy into an uncertain exile, or reduced it to a passive client, possibly shattering Catholic hegemony over religious dogma before it even began. Throughout the 7th Century, “the embryonic Celtic and the embryonic Roman Church contended with one another for the prize of becoming the chrysalis of the new society which was to emerge in the West,” Arnold Toynbee observed. Had the Arabs been victorious at Poitiers, the frontier of the caliphate would have advanced to the Loire, cutting the Curia off from its flock in western Europe. Accordingly, “Western Civilization would probably have been derived from an Irish instead of a Roman embryo.” This outcome is even more likely in the event Constantinople had fallen; no one apostolic church, but rather multiple competing doctrines, further splintering the few remaining Christian communities of Europe.

The sum total of Christian Europe at this point would have amounted to little more than the British Isles and the marginalized remnant of the Merovingian kingdom, both exposed to incessant Viking and Avar raids. The Arab attitude towards such pitiful fragments can be assumed from the protagonist of Harry Turtledove’s alternate history Islands in the Sea, set in a Europe dominated by the caliphate after the fall of Constantinople: “Let them be islands in the Muslim sea, he thought, if that was what their stubbornness dictated. One day, inshallah, that sea would wash over every island.” If the last Christian holdouts eventually came around to the true faith, so be it. The caliphs might have preferred they did not; a steady supply of franj taken as booty from the petty states of northern Europe would have been as welcome in the slave markets of the east as the zanj taken from Africa.

The long-term implications are of profound importance. Even assuming the ultimate disintegration of the caliphate, the successor states of Mediterranean Europe would have remained firmly within the Islamic economic and cultural orbit. While this would have empowered them to participate in the golden age of Islamic intellectual achievement, it also means they would have been assimilated into the fundamentalist backlash of al-Ashʿarī, al-Ghazālī, and Nizam al-Mulk. Would this have aborted the artistic efflorescence of the Renaissance? Without this foundation, could the scientific inquiry of the Enlightenment and the technological breakthroughs of the Industrial Revolution have ever occurred? At a social level, without the separation of faith and state, could constitutional government and representative democracy have evolved? Could policies from the abolition of slavery to the emancipation of women have ever been contemplated? Horizons everywhere might be narrower. With no Reconquista, al-Andalus would have remained permanently linked to the markets of the east through sea-lanes spanning the exclusively Islamic Mediterranean. There would have been no incentive to develop the nautical technology necessary for navigation on the open Atlantic in search of alternate trade routes to the Indies. In such a reality, the heirs to the Mexica and the Inca might still govern to this day in the isolation of a New World never disturbed by the Old.

The study of history, therefore, is by definition the study of alternate history; for to point out the importance of what did happen is to make a case that the implications of what might have happened otherwise are at least as significant.

Constantinople AD 717–18 is out now. Order your copy from the website now.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment