Osprey author, Myke Cole is on a research trip around Greece ahead of his upcoming book The Bronze Lie: Shattering the Myth of Spartan Warrior Supremacy. Read on to find out more about his first stop: Thermopylae.

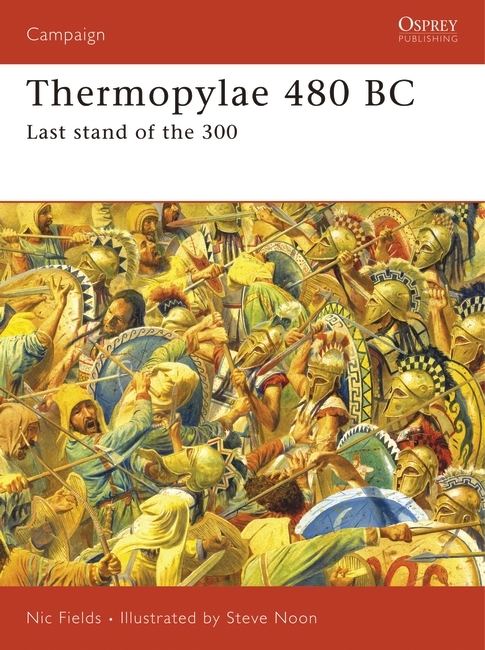

I’m writing this from Graviá, a tiny mountain town not far from Thermopylae, the site of the famous battle in 480 BC and the topic of Nic Fields’ great Osprey title Thermopylae 480 BC: Last Stand of the 300 (Campaign 188).

I also cover Thermopylae as one of four “focus battles” in my forthcoming book The Bronze Lie: Shattering the Myth of Spartan Warrior Supremacy, and I am here on a research trip surveying the battlefields for all four of those battles (the other three being – in date order from the oldest – Pylos/Sphacteria, Leuctra, and Sellasia). I got to use Nic’s book as a guide to surveying the battlefield, and dove a bit deeper on some of his sources as well.

Thermopylae is one of the most famous, popularly dramatized, and politically sensitive battles in ancient history. Much of this is due to the popularity of Frank Miller’s hit 1998 comic book 300 and Zack Snyder’s even more celebrated 2006 film adaptation of it. This battle, more than any other, laid the foundation for the Spartans’ legendary reputation as history’s greatest warriors. It’s a legend I examine in the book and one I’ve already started deconstructing in other short pieces. The popular myth is that Thermopylae was a glorious suicide mission, a fated last stand where 300 brave Spartans sold their lives so dearly and caused so many casualties that the massive Persian juggernaut they opposed was doomed to defeat at the later battles of Salamis (another great Osprey title – Campaign 222:Salamis 480 BC), Plataea (Campaign 239: Plataea 479 BC), and Mycale.

As I’ll argue in The Bronze Lie, I strongly disagree with this. I do not believe Thermopylae was a glorious last stand. It was a paltry three-day delay for the Persians, who went on to burn Athens. They could well absorb the casualties they sustained. The Greeks (the approximately 7,000 Greeks – not a mere 300 Spartans) utterly failed in their strategic objective – to delay the Persian army enough that its enormous size would cause it to starve. The land battle wasn’t even the main Persian objective. The real fight was at sea – off Artemisium – a scrap that Fields does good justice to in his book. The Spartan king Leonidas’ likely apocryphal response of “ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ” (“Come and take them”) to the Persian king Xerxes’ demand that the Spartans surrender their arms is an inspirational cry for the political right around the world (and in particular, pro-gun advocates in the US). It shouldn’t be. Because Xerxes did indeed come and take them, killing every Spartan and Thespian (all the other Greeks had either fled or surrendered) in the process.

The bronze statue of Leonidas at Thermopylae. Below him reads the ill-considered words in Greek: “Come and take them.”

The bronze statue of Leonidas at Thermopylae. Below him reads the ill-considered words in Greek: “Come and take them.”

Herodotus’ narrative of the battle has a Greek traitor named Ephialtes leading the Persians through a secret route (the Anopaia Path) after they fail to defeat the Greeks in the pass via a frontal assault. The problem with this story is it assumes the Persians were idiots who failed to perform critical pre-battle intelligence work. Persia was a vast and incredibly sophisticated empire in 480 BC and they were known for excellent use of intelligence. They were also known for meticulous preparation before invading Greece, including conducting reconnaissance, laying in stores, building roads, establishing lines of communication, and making diplomatic overtures to smooth the way. I cannot bring myself to believe they would have failed to reconnoiter at Thermopylae, and more importantly to have recruited an intelligence network of locals who provided Xerxes with an effective map of the area before battle was even joined. My point is this – Xerxes likely had several local guides in the area before he even showed up. The Anopaia path was no secret. Xerxes knew, and Leonidas knew he knew. Leonidas’ stationing of 1,000 Phocian troops to guard the pass is usually seen as a token force sent because Leonidas didn’t expect the secret to be discovered. I see this force as a legitimate blocking effort (very likely under a Spartan xenagos – a commander of non-Spartan troops) Leonidas was counting on to hold the path against the attack he knew would certainly come. 1,000 men is not paltry when you consider the example set at Marathon in 490 BC, when 10,000-odd Athenians and Plataeans soundly defeated a Persian army at least 2–3 times their number.

Fields uses as his guide to the Anopaia Path a 1980 article by Paul Wallace that originally appeared in the American Journal of Archaeology. I can see why Fields picked it – Wallace hiked the route himself, even going so far as to make the march at the exact same time as the Persians did (and only carrying the same amount of rations), timing where he arrived at each spot and matching that up to Herodotus’ description before settling on what he was certain was the correct route. I was impressed by the article and tried out Wallace’s first part of the path (the only part Wallace really disputes) – starting at the tiny village of Vardates, and on up to the mountain hamlet of Eleftherochori. Verdates is almost impossible to find; I was reduced to driving in the general direction and then using my horrible Greek to ask for directions. I got out of my car, took a picture of the town sign and cheered when I finally figured it out. It does match up to Wallace’s description, as does Eleftherochori, precipitously perched on the mountain at the end of a road with sheer cliff faces (and no guard rail) dropping off to one side. Cutting east from Eleftherochori, I made it some of the way toward Lake Nevropolis, which Wallace’s route suggests, before thick mud, lack of a road, and finally failing light forced me to head back. I’ll come back and try the route again in its entirety, but I do think Fields is on good ground starting with Wallace.

Vardates was so hard to find that I couldn’t resist taking a triumphal photo of the town sign.

View from just outside Eleftherochori. The town is perched on a mountain top with steep cliffs (and no guardrail in spots) on the drive up.

While the location of the Anopaia Path is in dispute, the location of the battlefield itself is not, owing largely to one thing – the Kolonos, the small hill where the Spartans and Thespians (and Thebans, but these surrendered before the last stand truly began) retreated and were killed to the last man. We know the Kolonos is the actual location because in 1939 Spyridon Marinatos excavated it, discovering around 100 arrowheads (and some spear heads) that matched known Persian designs (you can see these now in the Athens Archaeological Museum). This exactly matches Herodotus’ description that the defenders were surrounded and slaughtered with a hail of arrows. From the Kolonos, we can figure out the rest of the battlefield with a high degree of accuracy, further proven by the remains of the old Phokian wall (also found by Marinatos) that Herodotus tells us the defenders rebuilt and used.

The inscription atop the Kolonos hill, written by Simonides: “Go, traveler. Tell the Spartans we lie here, obedient to their laws.”

The remains of the Phocian wall the Greeks defended.

The hot springs from which the battle takes its name (Thermopylae means “hot gates”) are there, and there’s even a pool you’re welcome to take a dip in if you’re feeling brave (the water is really warm, but it also stinks like rotten eggs from the sulfur content. Some French tourists were swimming in it when I was there, but I declined). The rushing waters are beautiful – steam rises from them, and the rock beneath is bright teal-blue.

The hot springs from which Thermopylae gets its name. The rocks beneath are a vibrant blue.

Across the road from the Kolonos are the monuments for the battle, which are deeply moving, no matter what you think happened on that day in 480 BC. There’s the 1955 memorial to the 300, with Leonidas front and center – a striking bronze statue above his ... ahem ... rather ill-considered slogan (ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ). I prefer the 1997 memorial to the Thespian dead, despite the modern and extremely phallic sculpture (literally every friend I show it to immediately asks “why did they emphasize the penis?”) This is because while the Spartans get all the credit for Thermopylae, the truth is that their contribution was paltry compared to their available muster. The 700 Thespians who died represented an entire generation of fighting men for the much smaller city.

The memorial to the Thespian dead at Thermopylae.

I hope you’ve enjoyed these pictures from my tour of the battlefield, and that you’ll check out Nic Fields’ great guide, made even better by Steve Noon’s amazing illustrations. I’ll give my own detailed theory of what happened at Thermopylae when The Bronze Lie comes out.

For now, I have to hit the books – I’ll be heading about an hour southeast tomorrow to Leuctra, where, in 371 BC, Thebes snapped Sparta’s spine, ending Sparta as a militarily relevant power for the remainder of its history.

Follow Myke Cole here:

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment