In Martin Pegler's newest Weapon book, Sniping Rifles on the Eastern Front 1939–45, he explores the development of sniping weapons and techniques on World War II's Eastern Front. Today on the blog, Martin has curated a list of five best sniping rifles.

Compiling a definitive list of anything is a very subjective exercise. When something as specialised as sniping rifles are concerned, it becomes even more difficult as there are so many external contributory factors to take into account. What worked well in 1916 was not the case by 1944 and would be considered laughably inadequate in 2019. What’s more, the environments in which they were used were markedly different, for a rifle that worked perfectly in Western Europe may not function at all well during a Russian winter. The traditional use of converted military rifles for sniping was to prove a major stumbling-block for decades. Snipers were battlefield specialists, and it took a very long time for the armies of the world to appreciate that being a specialist required equipment that was purpose-built to enable them to perform their role efficiently. These factors are worth bearing in mind when drawing up any definitive list of ‘the best’. What I have tried to do is look impartially at the rifles used, and select those whose introduction formed a definitive evolutionary path. They were, to use a modern expression, ‘game-changers’. I hope you find the choice interesting, although you may not agree!

1. The New Model 1858 Sharps rifle

Why, you might reasonably ask? Most people with any knowledge of the Model 1858 Sharps would only think of it as ‘the buffalo rifle’. But these single-shot, breech-loading black-powder guns were pivotal in the history of military sharpshooting. They were the first specialist rifles to be issued on a large-scale basis to a unit who were employed as snipers – even if the term had yet to be coined. Prior to the American Civil War, rifled arms had been used by American patriots during the Wars of Independence, and later in modest numbers by the British during the Napoleonic Wars, in the form of the Baker rifle. But these were weapons of expedience, either civilian guns pressed into service, or rifles made in very small numbers for light infantry soldiers. But in 1862 some 2000 .52-calibre Sharps were specifically ordered and issued to two regiments of Berdan’s Sharpshooters. They were different to other Sharps rifles in military service, having a double-set trigger to provide a very light pull. A few were scoped, most were not, but in the hands of a good shot (and to be a Berdan man, you had to be an exceptional shot) they would prove deadly at ranges in excess of 1,000 yards. Although the fact was not recognised at the time, they were to set a precedent that took over a century to be recognised. To enable a sharpshooter to reach his full potential, his rifle must be the best there is.

A Berdan New Model 1858 Sharps rifle. At first glance, it resembles the infantry pattern issued with its iron patch-box and case-hardened receiver. It fired a .52-calibre 350-grain conical bullet, propelled by 64 grains of black powder. The 30-inch barrel ensured a full burn of the powder in the combustible linen cartridge, to provide maximum velocity and range.

A Berdan New Model 1858 Sharps rifle. At first glance, it resembles the infantry pattern issued with its iron patch-box and case-hardened receiver. It fired a .52-calibre 350-grain conical bullet, propelled by 64 grains of black powder. The 30-inch barrel ensured a full burn of the powder in the combustible linen cartridge, to provide maximum velocity and range.Image courtesy of Martin Pegler.

2. The Mauser Gew.98 sniping rifle

It was not until the outbreak of World War I that any country fielded a purpose-made sniping rifle that had a factory-fitted optical sight. Pre-war, Germany and Austria were the leading nations for the supply and use of telescopic-equipped hunting rifles, having access to both good quality optical glass and a wide range of suitable rifles. As hunting was almost a rite of passage for young German men, a larger portion of the population were used to handling these rifles than in any other European country. As war loomed, the army ordered that a Scharfschutzen-Gewehr 98 (sharpshooter-rifle Model 98) was to be manufactured using the standard 7.92mm Model Gew.98 rifles fitted with commercially available sights and bases. As a result, dedicated sniping rifles began to be issued from late 1914 onwards. There were myriad different patterns of scopes (at least nine are known), but all used predominantly two forms of quick-release claw mounts, either partially offset or fully offset. Scope magnification was modest by today’s standards, usually 3 or 4 power, which provided a sniper with a reasonable chance of a head shot at 200 yards, or a body hit at 400 yards. The rifles were factory selected for accuracy and the scopes installed by military contracted gunsmiths or skilled armourers. Being hand-built, each was unique, and scopes were rarely interchangeable. The Germans pioneered the tactical employment of snipers in the front lines and for a year or so, this gave them an apparently unassailable edge, but eventually Britain began to train its own snipers and manufacture its own optically-equipped rifles. Nevertheless, for the duration of the war, the Mausers remained the best sniping rifles to be fielded by any country.

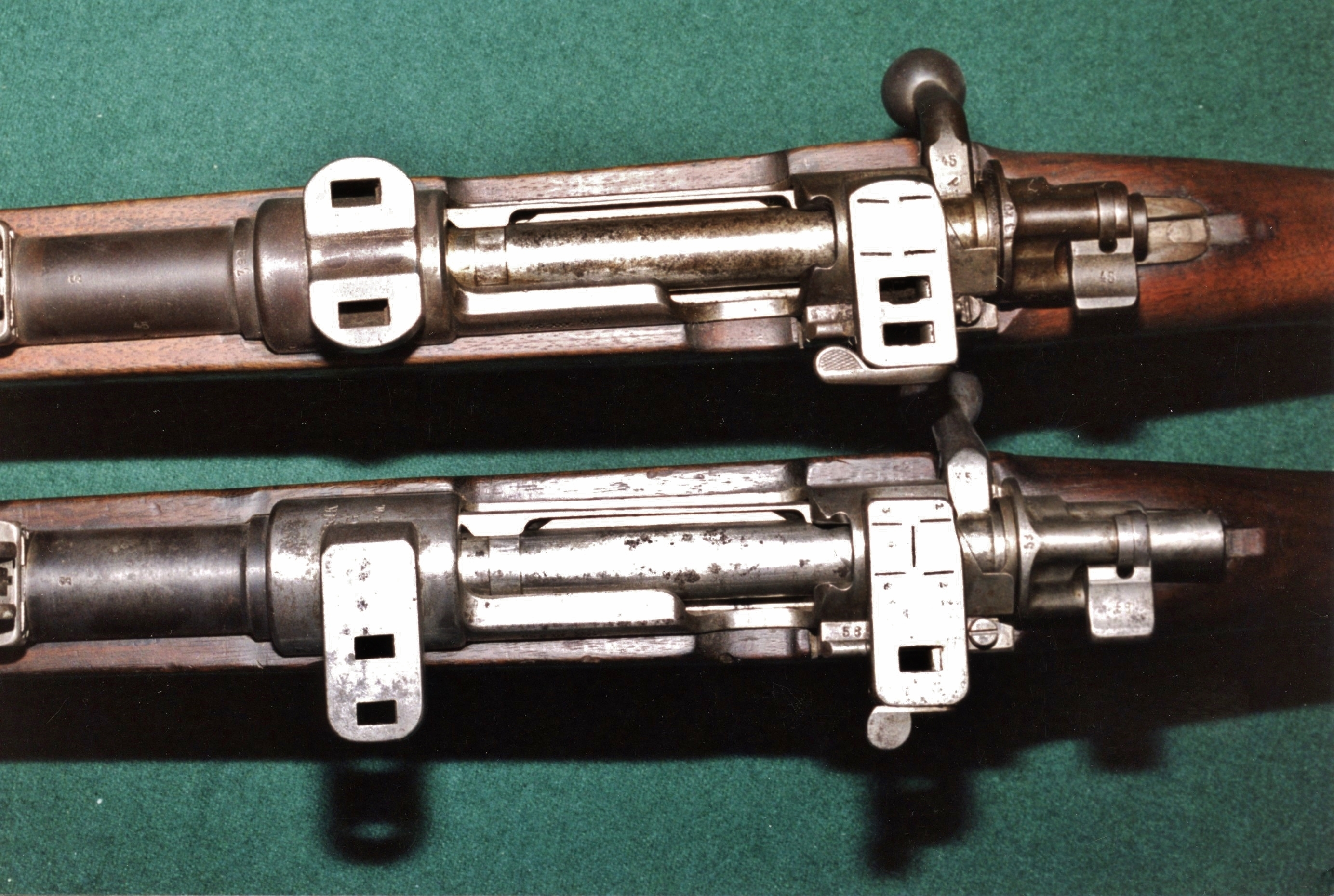

Two World War I-manufactured Mauser Gew. 98 rifles showing (top) the partially offset scope mountings and (bottom) the fully offset mounts. The ensure the scope was in line with the bore, the mounts were curved to the right, and bridged, to permit the shooter to use the iron sights.

Two World War I-manufactured Mauser Gew. 98 rifles showing (top) the partially offset scope mountings and (bottom) the fully offset mounts. The ensure the scope was in line with the bore, the mounts were curved to the right, and bridged, to permit the shooter to use the iron sights.Image courtesy of Martin Pegler.

3. The Enfield No.4 (T) sniping rifle

In the wake of experience gained in World War I, one might reasonably expect Germany to have been the leaders in the sniping war. Initially this was the case, Britain having nothing but end-of World-War I sniping rifles such as the Pattern 1914 Mk 1* W (T) A. A new weapon, based on the current issue .303-inch Enfield No.4 Mk 1 rifle was needed, so 1,403 were selected for sniper conversion by means of being mated to a cast bracket with the No.32 Mk 1 scope (originally developed for use with the Bren gun). Between September 1940 and March 1941 these rifles were trialled, and they proved to be tough, accurate and comfortable to shoot. All production rifles selected for sniping had to produce above-average accuracy when test fired, and once set aside each was paired to its scope, then carefully rebuilt. The work was undertaken, not by the over-stretched factories but by Holland and Holland, the highly respected London gunmakers. This meant that each rifle was totally stripped then re-built by a skilled gunsmith. They were to be the first custom built issue military rifles, and after 1943, all were stamped with special codes to denote H&H fabrication. The scopes went through three patterns, mostly to correct defects in the workings of the elevation and windage turrets and simplify adjustment. They were of 3 power, graduated to 1,000 yards and with the bracket weighed a not inconsiderable two pounds. As one British sniper dryly remarked, ‘If I run out of ammo, I can beat the Jerries to death with the scope.’ The combination proved to be a winning one, and the No.4 (T) was arguably the finest sniping rifle issued to any of the warring powers during World War II.

Image courtesy of Martin Pegler.

4. The Remington 700

Until the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, sniping rifles were converted military arms, usually fitted with inadequate commercial hunting scopes. The process of improvement was a glacial one, and it was not until post-1945 that it began to dawn on the world armies that no mass-produced military rifle would be able to compete in terms of accuracy with a custom-built sniping rifle. During the Korean War American experiments with commercial Winchester Model 70s mated to 8- or 20-power Unertl scopes had proved encouraging, so when the Vietnam War drew the United States into South East Asia in 1965, the US Marines quite reasonably decided that they needed a competent sniping rifle that was not based on the current semi-automatic M14 combat rifle. They chose the solidly constructed 7.62mm Remington 700, a Mauser-actioned sporting rifle with a good reputation for accuracy and toughness. Usefully, these were available in large numbers commercially, and in a landmark decision they were to be fitted, not with an off-the-shelf commercial scope, but with the James Leatherwood designed ART 3x9 drop-compensating scope, which enabled a competent sniper to make first round 900-meter hits. The rifles were designated the M40 and introduced in 1966. Some problems arose due to the jungle humidity and the wooden stocks were replaced by a non-warping McMillan manufactured fibreglass stock with an improved M40A1 model. This combination of a custom-built rifle and specifically designed optical sight gave the American snipers an unparalleled advantage during the war and pointed the way forwards for future sniper rifle design. The rifle is still in Marine Corps service with a new variant, M40A7 shortly to be introduced.

An early Remington manufactured M40 rifle with Leatherwood scope, as issued in the early years of the Vietnam War. Note the lack of iron sights, one reason most snipers also chose to carry an M1 carbine or later, an M16 rifle. The shaped wooden stock was ideal for hunting in temperature climates, but warped badly in the jungle of South East Asia.

An early Remington manufactured M40 rifle with Leatherwood scope, as issued in the early years of the Vietnam War. Note the lack of iron sights, one reason most snipers also chose to carry an M1 carbine or later, an M16 rifle. The shaped wooden stock was ideal for hunting in temperature climates, but warped badly in the jungle of South East Asia.Image courtesy of Martin Pegler.

5. The Accuracy International L96

Building upon the experience gained by the United States in Vietnam, and the poor performance of the British Army’s 7.62mm Enfield L42 sniper rifles during the Falklands campaign of 1982, it was decided that a totally new concept of sniping rifle was required to equip British snipers. Based on a design by gold-medal winning Olympic shooter Malcolm Cooper, the Accuracy was utterly different to anything seen before, being a modular system employing an aluminium chassis and two-piece moulded polymer stock with thumbhole, heavy free-floating stainless-steel barrel and Schmidt and Bender 6x42 sight. It was introduced as the 7.62mm PM (Precision Marksman) rifle in 1982 but soon became known as the AW (Arctic Warfare) model as it was modified to cope with sub-zero conditions. Officially adopted as the L96A1 then latterly the L118A1, it went through several upgrades, with short and long actions being produced to enable it to chamber cartridges such as .300 Winchester Magnum and .338 Lapua Magnum as well as a scaled-up variant, the AW50, that chambered the BMG .50-inch cartridge. In 2007 the .338-inch AWSM L115A3 was introduced, rendering the old 7.62mm NATO round redundant for sniping, the L96 rifles being downgraded to sharpshooter use. With a multi-functional Schmidt and Bender L42A1 5-25x scope it provided effective fire out to 1,700 metres. Indeed, for some time, it held the record for the longest recorded kill, at 2,475 metres when Cpl Craig Harrison shot two Taliban fighters. The design continues to go from strength to strength, with the introduction in 2012 of the AXMC, a multi-calibre rifle with a QD barrel/bolt assembly that can be changed to chamber .338-inch, .300-inch or 7.62mm ammunition. The Accuracy International series still remains at the pinnacle of modern sniper-rifle design and construction.

Image courtesy of Martin Pegler. To read more, order your copy of Sniping Rifles on the Eastern Front 1939–45.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment