In today's blog post, Mark Lardas joins us once again, this time exploring the firebombing raids against Japan in the 1940s. The bombing raids are the focus of his new book Japan 1944–45, which examines the air campaign that incinerated Japan's cities.

The B-29 campaign against Japan is best known for its firebombing raids. Most people today picture the raids with the heavens filled with dozens of Superfortresses raining fire on a city. Not in formation, but loosely spread across the night sky. I remember such a painting on the cover of the first book I read about the campaign, back in the 1960s, while still a youngster.

I assumed it had to be true. The men who flew those missions were then in their forties to sixties. Most who survived the war were still alive. Surely they would object if that cover was wrong. Except those men either did not object or were ignored. Maybe the European fire-bombing raids were like that, but the raids on Japan were much different – yet possibly even more horrifying.

Night raid over Akashi, 7 July 1945. Featured in Japan 1944–45.

Night raid over Akashi, 7 July 1945. Featured in Japan 1944–45.

Artwork by Paul Wright.

There were never dozens of aircraft over a city simultaneously. Even during the fire raid on Tokyo on March 9/10 there were unlikely to have been more than six over the city at one time. A more typical number would have been two or three.

The reason lies in the nature of the nighttime fire raids. Wings did not fly in formation as they did for the daytime raids. Each aircraft took off, heading individually for the target. Aircraft arrived over the target spaced at the takeoff intervals. Since B-29s cruised at 290 miles per hour, a 30-second to 45-second interval between takeoffs spaced bombers 2½ to 4 miles apart.

This allowed bombers to carry a much bigger bombload.They did not have to carry fuel to be spent circling over their airfield, waiting for every aircraft to join the formation. That fuel could be traded for extra incendiaries. Additionally, LeMay planned the aircraft to come in at low levels – 4,900 to 9,200 feet, further reducing fuel load. Aircraft did not spend fuel climbing to 30,000 feet. They also burned less fuel cruising at 10,000 feet instead of 30,000 feet. Still more incendiaries could replace the weight of unneeded fuel.

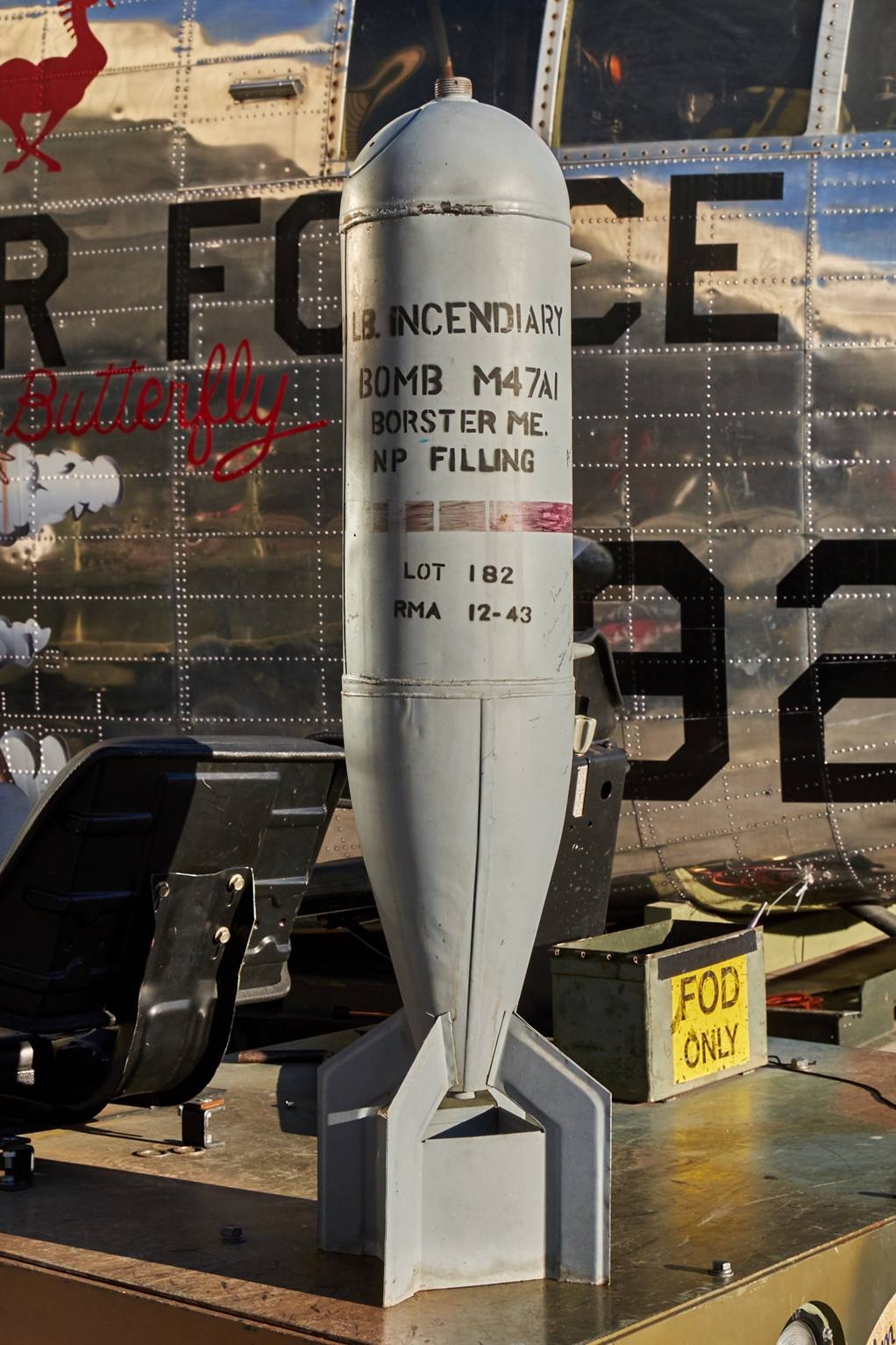

Incendiary Bomb (Greg Kenny, Palm Springs Air Museum)

Incendiary Bomb (Greg Kenny, Palm Springs Air Museum)

That meant fire raids lasted one hour to two hours. Instead of a wave of fire from the sky, a trickle came down. First one Superfortress drops a load of incendiaries. That first plane, a pathfinder, carried 60-odd M-47 bombs, napalm-filled 115-pound M-47s. That one B-29 would start several dozen major fires. Thirty to sixty seconds later, the next pathfinder drops its bombs in an unlit part of the city near the first set of fires. Several dozen more fires start. Then in another 30 to 60 seconds another pathfinder drops its load of M-47s. The process repeats until the pathfinders are through.

On the ground, firefighters are responding. Each fire started by an M-47 requires the attention of a fire engine. An air warden with a bucket of sand cannot extinguish a fire started by 100 pounds of napalm and white phosphorus. Tokyo had 1,117 fire engines, of which 716 were motorized pumper trucks with a pump capable of spraying 350 to 500 gallons of water per minute. It had 11 fireboats with 500-gallon pumps. The remaining fire engines were hand-drawn units capable of pumping 120 gallons per minute. At the end of ten minutes over 1,000 fires demand the attention of fire engines.

That is the beginning. Thirty seconds after the last bomber drops its load of M-47s, a B-29 carrying the six-pound M-69 incendiary drops its load. This plane carries nearly 1,000 M-69s. Each cluster scatters over an acre, 43,500 square feet – or an average of one M-69 every 43 square feet. Some land on pavement or dirt. But 50 percent of the Akuza area, the target of the raid, is covered by roof, most of which can burn. So 500 or so of the M-69s can start fires.

M-69s can be extinguished with a bucket of sand. But how many civil defense wardens are there, and how many buckets of sand does each one have? The available manpower cannot douse all of the incendiaries before these, too, start fires requiring a fire engine to contain. But every fire engine is already committed.

And it is 30 seconds later and another B-29 drops another 1,000 M-69s. Then another. This goes on for over an hour.

This is the real horror of the fire raid. It grows drop by drop. It cannot be stopped once out of control. The uncontained fires grow and spread. Soon fire is everywhere. All that can be done is to run. The civilians on the ground cannot do anything to stop it.

Since the density of aircraft is so low, why can antiaircraft guns and night fighters not deal with the attackers? The B-29 crews believed that before the first raid. They were sure they were doomed. Tokyo had the heaviest antiaircraft defenses of any city in Japan: 500 guns. They were well laid out. But two things eliminated most of their effectiveness. The first was that the shells were fused at the height the Japanese assumed the Superfortresses were at. Their early warning radar did not give altitudes.

Previously B-29s always attacked Japan at 30,000+ feet, so shells were set to explode high. Only that first night raid came in low. The lead aircraft completely avoids flak. By the time the Japanese realize what has happened and correct their fuse settings, minutes have passed. Or tens of minutes. By then the fires are spreading, creating smoke and degrading visibility. But still, a few of the B-29s in the middle of the raid get shot down.

Then the other issue kicks in. The fires spread so fast and so broadly, communications fail. Antiaircraft fire can no longer be coordinated. The gun positions closest to the target area are overwhelmed by flames and must be abandoned.

The night fighters – with a top speed barely higher than the B-29’s cruising speed – are also at 30,000+ feet. By the time they get the word, and come down to the right altitude, most of the bombers were ahead of them. They, too, were ineffective.

Tokyo was the best defended city in Japan. Many cities, especially those smaller than Japan’s ten largest cities, had no antiaircraft guns. There were not enough to go around.

Surprisingly, the fire raids on Japan were remarkably survivable under most circumstances. The March 9/10 Tokyo raid turned into a horror which killed between 60,000 and 130,000 people due to a number of factors. The first was its unexpectedness. It was larger than any previous fire raid and it caught people off-guard. They sheltered in place, when they could have run, and once they realized their danger it was too late to outrun the flames. The wind and relatively dry weather whipped the flames into a firestorm, a phenomenon that sucks the oxygen out of the atmosphere and creates unsurvivable blast-furnace temperatures.

But a standard fire raid built slowly, drop by drop. If a healthy adult started moving when the raid started towards open ground, upwind of the bombs, they could generally get to safety. The Akashi raid, illustrated in a plate in the book, burned out 60 percent of a town with over 80,000 inhabitants. Yet only 355 people died. The town was evacuated one hour before the attack began, with one-third of the population – older adults and children – sheltering in a park north of the town.

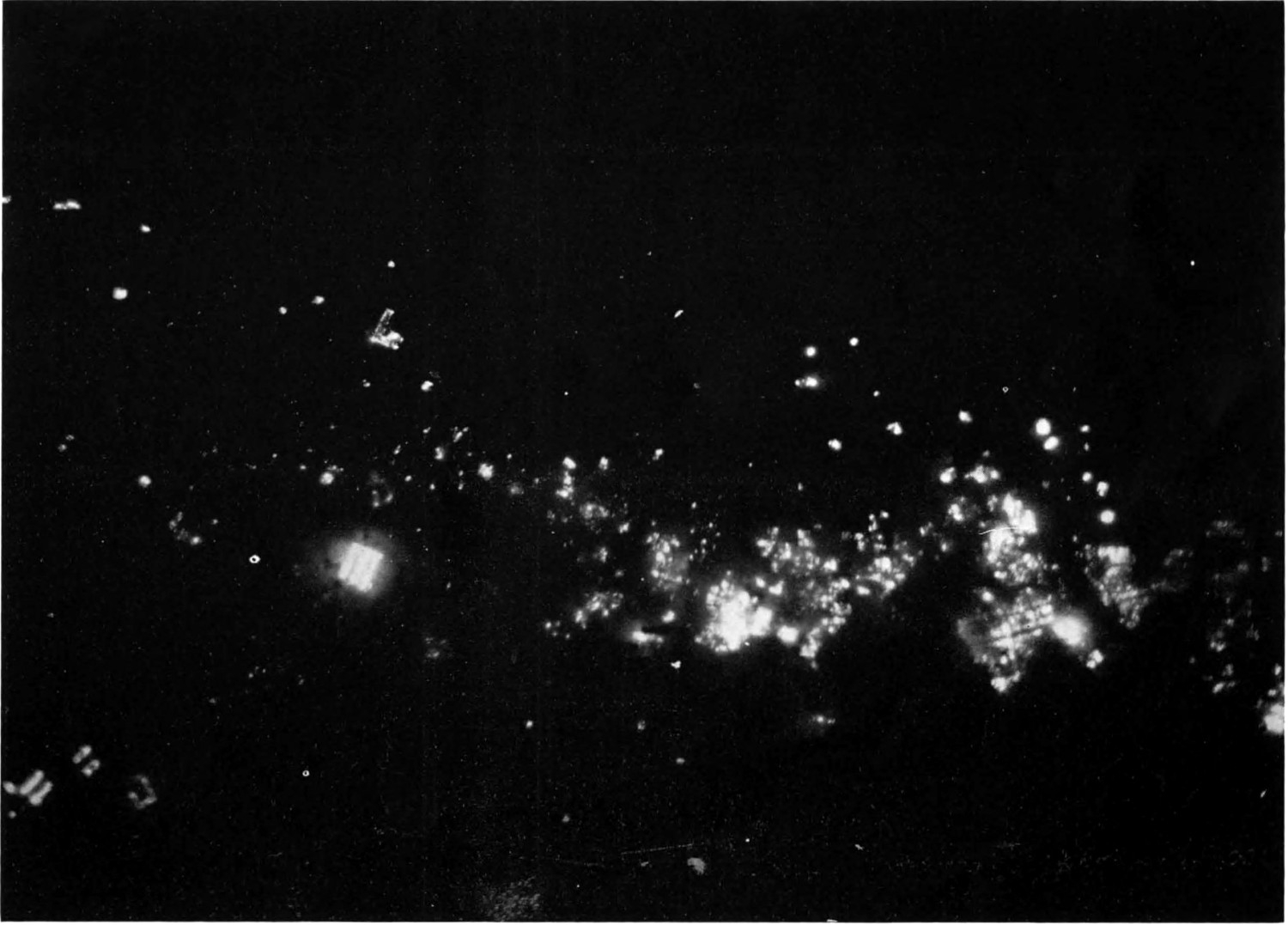

Bombing of Ube - Fires Started Early in Attack (US Strategic Bombing Survey)

Bombing of Ube - Fires Started Early in Attack (US Strategic Bombing Survey)

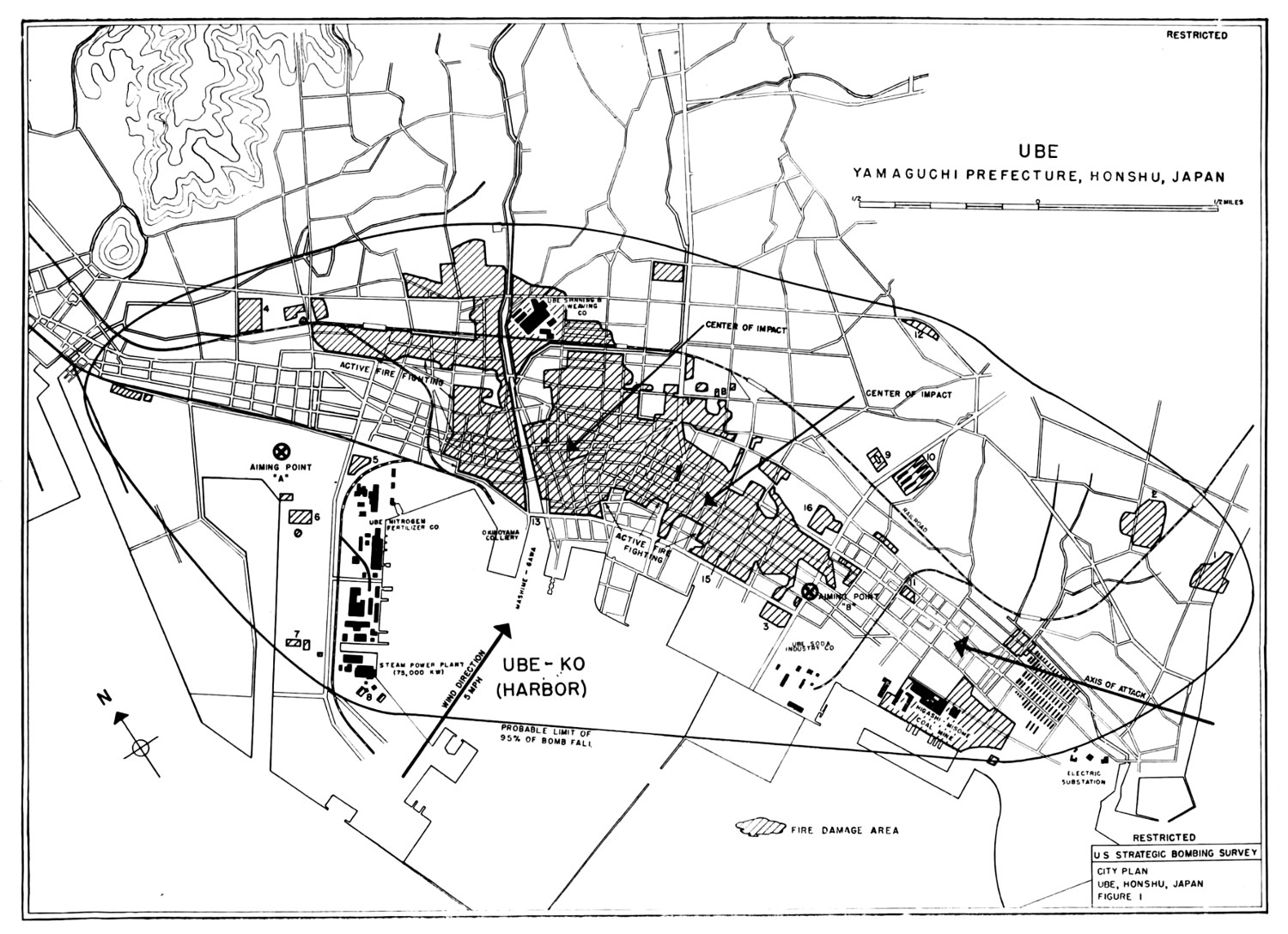

Similarly, Ube (pictured at the beginning of the July 5 fire raid) was a town of 100,000. Despite the damage to the city shown on the US Strategic Bombing Survey map made after the war, only 230 died in the attack. In both cases an inhabitant’s home and place of work (often co-located) was gone, but at least they were alive.

Ube Bombing Results (US Strategic Bombing Survey)

Ube Bombing Results (US Strategic Bombing Survey)

It was fine with LeMay if the population survived. He was trying to destroy Japan’s industrial capability, not kill its people, especially civilians. Once Japan’s inability to stop nighttime fire raids became obvious, he had leaflets dropped on targeted cities the day before the raid, urging civilians to evacuate. He was willing to be brutal, but glad to avoid unnecessary killing.

Read more about the campaign's objectives, its execution and aftermath in Mark Lardas's Japan 1944–45.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment