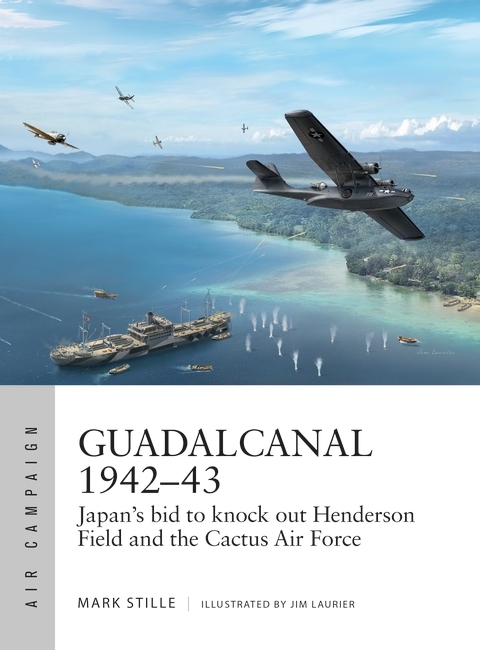

On the blog today, Mark Stille, looks at some of the myths that occurred during the campaign for Guadalcanal, the subject of his latest book, Guadalcanal 1942–43.

The campaign for Guadalcanal is one of the best known of the Pacific War, but it remains misunderstood from several important perspectives. My latest Osprey book on Guadalcanal, the Air Campaign Guadalcanal 1942–43 is another attempt to clear up some of the misunderstandings and myths surrounding this epic campaign.

When it comes to the air campaign over Guadalcanal, it is obvious that it was the decisive air campaign of the Pacific War. Including the two carrier battles during the campaign, both of which inflicted heavy losses on the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Air Force, the six-month campaign by the Japanese to knock out American air power on Guadalcanal was nothing less than a disaster. Not only did the IJN’s air units fail in their mission to gain air superiority over and around the island, but the Japanese suffered calamitous losses in the process. IJN aircraft losses are hard to determine with certainty, but approached a total of 700. Even harder to ascertain is the total of Japanese air crew losses. American aircrew losses are much easier to determine. Between Navy, Marine, and Air Corps units, some 420 aviators were lost. In comparison, Japanese aircrew losses were at least twice as many and maybe as much as three times as many. In comparison, 110 Japanese aviators were lost at Midway. The raw number of Japanese aviator losses is bad enough but does not take into account that these were the cream of the IJN’s highly-trained prewar aviators. Once they were gone, they could not be replaced and the effectiveness of Japanese air operations suffered accordingly. This degradation was evident in 1943 as the war moved up the Solomons and accelerated until in late 1944 the Japanese were forced to give up on conventional air attacks.

Another myth exploded during the Guadalcanal air campaign was the invincibility of the Japanese “Zero” fighter. American losses in air combat for the period 7 August through 15 November were 109 aircraft, including 70 Wildcats (the standard Navy and Marine Corps fighter) and 13 P-400/P-39 (the terrible fighter which the Air Corps brought to the island). Losses of the vaunted Zero during the same period were 106. Not all of these were due to air combat, but the great majority was, making Zero losses greater then Wildcat losses. The nimble and long-ranged Zero had gained an early-war reputation for invincibility primarily since it was piloted by combat-experienced pilots. For the first time, American Marine and Navy fighter units on Guadalcanal found a way to capitalize on the Zero’s principal weakness which was its extreme vulnerability to damage. This was due to some outstanding American small unit leadership. Marine squadron commanders came up with a set of tactics which played on the strengths of the Wildcat and avoided the strengths of the Zero. These tactics avoided dog fighting with the Zero, but late in the campaign the American fighter pilots were confident enough to take on the Zeros directly. Even at this early period of the war, the Japanese were having problems replacing losses and the overall state of training was so deficient that the Japanese were forced to pull units from combat for remedial training. American pilots, almost all of which had no combat experience before arriving on Guadalcanal, proved to be more adaptable and ultimately superior airmen, in spite of the fact they were flying an “inferior” fighter.

The problems of the Japanese aviators were exacerbated by the way the Japanese were forced to fight the air battle. The major Japanese base at Rabaul, from which almost all Zero and bomber sorties originated, was 565 miles from Guadalcanal. This limited the number of sorties the Japanese could mount, increased operational losses, and put the Japanese in a tactical box when planning air operations. As a result, the Americans quickly learned how to cope with the daily bomber raid, escorted by Zeros, which came over the island at the same time each day. From coastwatchers and radar, American fighters were in a position to take a daily toll from the Japanese. Japanese bombers were ineffective during the campaign – they accounted for only a small number of aircraft destroyed on the ground and never succeeded in knocking the airfield out. The Japanese 11th Air Fleet based in Rabaul proved it was not up to the challenge of defeating the small American air force on Guadalcanal. Not until late in the campaign did the Japanese develop other bases closer to Guadalcanal which would allow the Japanese to bring their superior numbers to bear. This was a classic case of too little, too late. It is fair to say that IJN lost the air campaign over Guadalcanal because of a lack of bulldozers.

The other theme of the book is the effort by the Cactus Air force to stop the flow of Japanese reinforcements and supply to the island. This highlighted the interdependence of air, naval and ground forces in the campaign. For the Americans, even a small number of attack aircraft on the island prevented the Japanese from bringing more troops there unless it was as part of a major convoy operation or as part of the nightly “Tokyo Express” which was inefficient and was unable to move heavy equipment. As long as the Cactus Air Force was intact, the Japanese could not move enough troops to overwhelm the Marines on the ground. The basic need to reinforce the ground forces on both sides drove the air campaign as well as the six major surface engagements of the campaign.

Leadership also mattered. The American commander, Vice Admiral William “Bull” Halsey kept his promise to the Marines that he would support them with everything he could get his hands on. He drained the South Pacific of every available Navy and Marine fighter, dive-bomber, and torpedo squadron and sent them to the island. When the Japanese mounted two major operations to move troops to the island in larger convoys, Halsey committed whatever ships he had as well. On the other hand, Admiral Yamamoto Isoruku was tentative and never marshaled his superior air and naval forces for a knock-out blow. When he made a major effort, it was mismanaged. The salient example of his ineptitude was in November when he sent a convoy to the island, and complete destruction, before he ensured the Cactus Air Force had been neutralized. Yamamoto’s performance at Guadalcanal should cement his reputation as one of the most overrated admirals ever.

Guadalcanal 1942–43 is one of the first focused examinations of the air campaign and tries to explain why the Japanese were so ineffective and how the Americans kept the airfield on the island operational for almost the entire campaign. More than just an examination of the numbers and types of aircraft, it places the operations of both sides into the context of their overall strategy and provides insight into why the most decisive campaign of the Pacific War turned out in the Americans’ favor.

Guadalcanal 1942–43 publishes on the 28th of November. Preorder your copy here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment