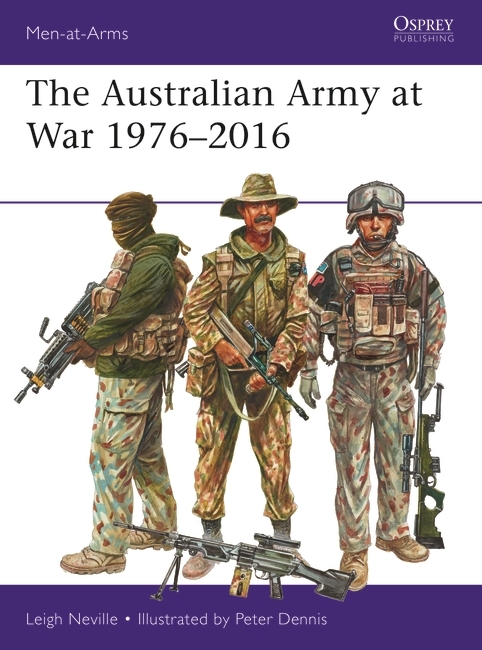

In today's blog post, Leigh Neville, author of The Australian Army at War 1976-2016, gives a fascinating overview of the Diggers' missions since the end of the Vietnam War.

‘The Australian Army has been certainly one of the world’s busiest since September 1999,’ explains Leigh Neville, the author of the new Men-At-Arms title, The Australian Army at War: 1976-2016. ‘Before East Timor and INTERFET however, it really was a different story…’

INTERFET or the International Force East Timor was a United Nations (UN) task force, led by Australia, which successfully intervened in the humanitarian crisis occurring in the Pacific nation after a referendum which saw the majority of East Timorese vote for independence from Indonesia. Pro-Indonesian militias, often including members of the Indonesian military, caused havoc through arson and murder. After United Nations operations were halted due to the unrest, Australia responded with Operation Spitfire, a non-combatant evacuation of UN and associated personnel.

With the violence only increasing with the departure of the UN, Australia led the way for a UN Security Council resolution to stop the militias and restore order. In September 1999, the first Australian units, drawn from the Special Air Service Regiment (SASR) and the Commandos of the 4th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (4RAR), landed in the capital, Dili. They were soon followed by regular infantry from the 2nd Battalion RAR (2RAR) and a pair of armoured personnel carriers. Thankfully this show of force gave the militias pause and the intervention forces quickly secured the capital and airport before fanning out into the country.

‘INTERFET was an eye-opener for the Australian Army, and the ADF (Australian Defence Force) in general. It was the first time a significant force element had been deployed overseas since Vietnam, it was the first time such an element had been solely Australian-led, and it was easily the largest operation undertaken by the ADF in almost 30 years’, says Neville. ‘Unbeknownst to the Army, it was also the perfect dry-run for later deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq – it showed up a lot of deficiencies that could only be expected from a peace-time Army with very little operational experience.

‘One of the participants I interviewed, retired Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Yeaman who later commanded a rotation of the Reconstruction Task Force in Afghanistan, told me quite bluntly that, in his words, “Timor was indeed a wake-up call, and we were extremely lucky that we did not face a serious opposition – the Taliban, or Iraqi insurgents would have carved us up”.’

Prior to INTERFET the Australian Army had experienced a decades-long period derisively known as the ‘Long Peace’. After the Vietnam War, the Army suffered from years of neglect in terms of both equipment modernisation and training. Successive governments, wary of the Vietnam effect, kept the ADF on a short leash although a succession of peace-keeping deployments provided some limited operational exposure. INTERFET finally restored confidence in and within the Army and the wider ADF with a growing realisation that Australia could not always depend on the United States to lead and sustain expeditionary missions.

Only two short years later, the Australian Prime Minister pledged his support to the United States after the events of 11 September 2001 and Australian special operations forces (SOF) were amongst the first to join American forces in Afghanistan in December of that year. Bringing with them their own vehicles, something which inexplicably many Coalition nations’ SOF did not, meant that the Australians could be effective from day one.

‘That first deployment of the Special Forces Task Group, made up of a squadron group from SASR, really set the tone for operating with the Americans in Afghanistan. The SASR guys immediately started looking for work and convinced the US Marines, and in particular “Chaos” himself, then General James Mattis, that they could provide a unique long range reconnaissance capability. Mattis loved the SASR guys and his staff were astounded by the quality of the intelligence they received from these mounted patrols pushing out from Camp Rhino. It really was a case of pointing at a map and saying, “hey we have no idea what’s in that area” and the SASR heading out on their motorbikes and six-wheeled Perenties to report back and fill in those blanks.

‘This was still early days for ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) and the Coalition had nowhere near the kind of drone and manned overhead assets that they do today. Mattis needed to know what was out there and the SASR guys provided him with that knowledge. The long range reconnaissance capability was, and still is, one of the core capabilities provided by SASR – for a long time during the 1970s it was the Regiment’s primary mission in the defense of Australia and kept the unit afloat until it received the national counter-terrorism mission which revitalised SASR.’

Iraq followed and Australia became one of a handful of Coalition nations to pledge operational support to the United States. Again the SASR was deployed to provide their by now highly respected reconnaissance capability. Working alongside US and British SOF in western Iraq, SASR again acquainted themselves exceedingly well in the eyes of their allies. For the US, SASR was now considered on par with their own Tier 1 special mission units.

The Australian Army returned to Afghanistan in 2005 with another SOF task force, followed a year later by the first Reconstruction Task Force which included elements of the 1st Combat Engineer Regiment (CER) which would lead the reconstruction and ‘hearts and minds’ effort. Under the protection of both infantry and cavalry units, the engineers built infrastructure projects in Uruzgan Province including a trade school to educate local Afghans in carpentry and associated trades.

‘The RTF was very successful locally – it showed the Afghans that the Afghan government, through the Australian forces, could provide a tangible benefit. Sadly, just like elsewhere in Afghanistan, the programme was constantly under threat from rival tribal groups and the Taliban who delivered “night letters” threatening Afghans who worked with the Australians. Stuart Yeaman told me, “what the trade school did do for the local population was that it provided money to families that might otherwise have had to grow (opium) poppy or work for the Taliban to generate cash. It did also generate goodwill. How much goodwill we will never know, but it was symbolic of an attempt to improve the lives of ordinary Afghans.”’

Neville argues that the counter-insurgency effort was likely too little, too late. SASR and the Commandos along with providing force protection by clearing the RTF’s operating areas of insurgents, were also conducting ‘night raids’ targeting Taliban high value targets including bomb makers and leadership. The raids were uniformly unpopular with the Afghan people and may have directly impacted on the gains made by the RTF.

Today, the Australian Army continues to provide training support to Afghan security forces and since 2014 have been deployed to Iraq to assist in the battle against Islamic State. Neville comments, ‘The Army has spent a lot of time in Iraq. After the invasion, there were Australian elements protecting the diplomatic mission in Baghdad and later a battle group was deployed to southern Iraq to maintain security and train Iraqi security forces. That ended in 2008 with the status of force issues which were beginning to hamper Coalition operations. The Army returned in 2014 under Operation Okra with both Australian conventional forces and SOF again training and mentoring Iraqi units in the fight against Islamic State. Some of the Commandos forward deployed with their Iraqi counterparts into Mosul during the battle to recapture the city and provided targeting support, calling in Coalition artillery and close air support.’

In summing up, Neville argues that the Australian Army has undertaken a dramatic evolution since the days of the ‘Long Peace’, ‘For many years after Vietnam, the Army was almost forgotten about. Certainly in terms of funding it was, let alone the lack of willpower to deploy them outside of very limited peace-keeping operations like Somalia. INTERFET and Timor changed all of that – that was the point certainly. From there, the Army has benefited from more than a decade of operational experience in Afghanistan, in Iraq, and on regional missions to the likes of the Solomon Islands. It can and does punch well above its weight.’

To find out more, pre-order your copy of The Australian Army at War 1976-2016.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment