In September 1939, Nazi Germany launched its infamous Blitzkrieg invasion of Poland, bringing about the outbreak of World War II. Today's blog post, an extract from Robert Kirchubel's Atlas of the Blitzkrieg 1939–41, looks at the aerial operations at the beginning of the campaign.

"Fall Weiss set the standard for beginning an attack used by nearly every conventional operation since: An aerial assault against the enemy’s air force, ground troops and national infrastructure. Contrary to popular myth and German propaganda, the Luftwaffe did not obliterate the Polish Air Force in the campaign’s first couple of days, although German numbers and quality eventually did turn the tide in the attackers’ favour.

Approximately one‑third of the Luftwaffe’s aircraft – 1,939 of an available 2,775 – took part in the east. At this early stage of World War II, the air force had not been completely subordinated to the army, so had its own independent plan against Poland. Some Luftwaffe leaders, aircrew and ground staff had tasted combat in Spain, but most had no practical experience. The Poles had about 1,929 machines, almost half of which carried bombs, mostly for tactical missions. Around half of its inventory comprised first line aircraft, though even many of these were obsolete. Most of the Polish Air Force flew in support of the army.

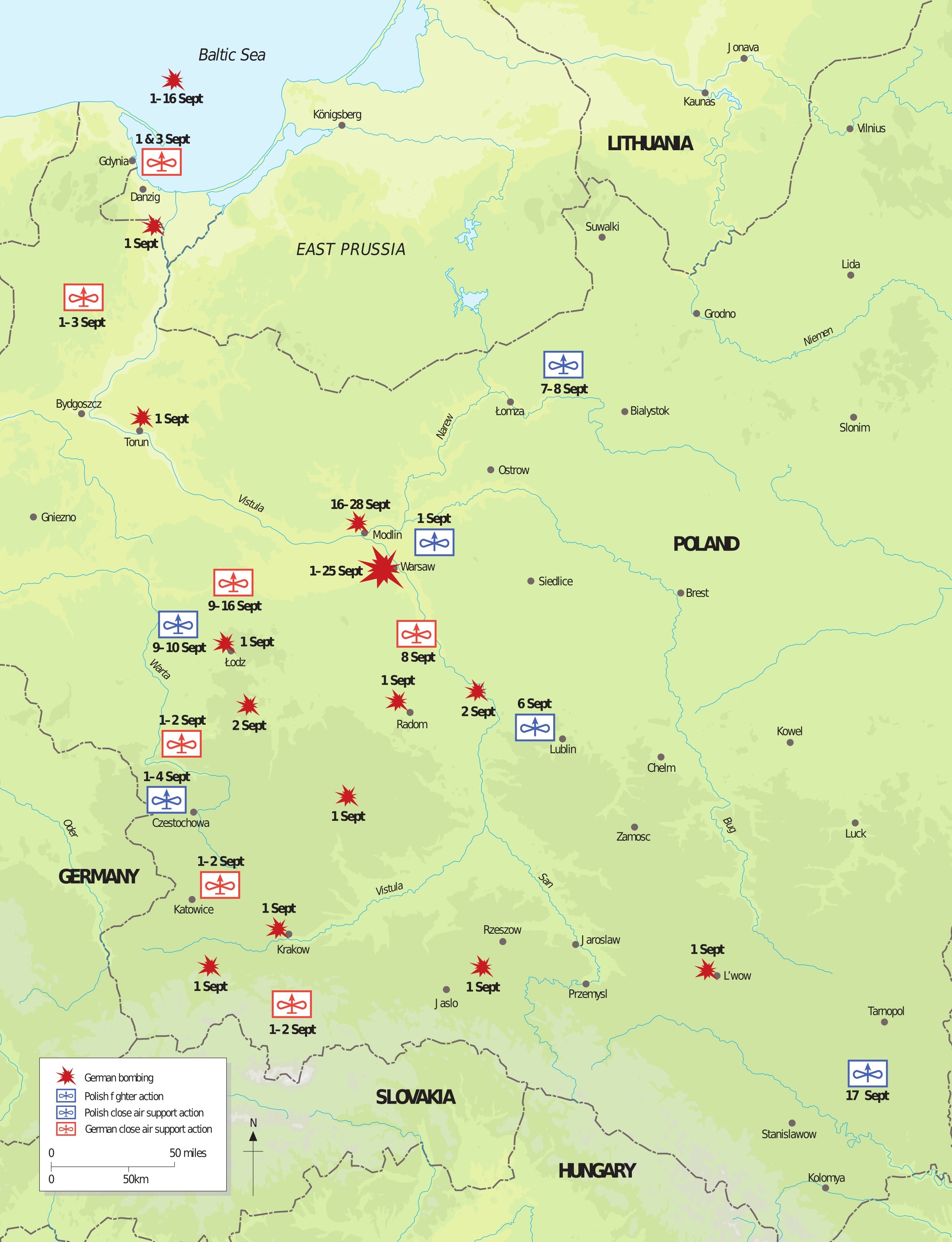

During the initial period, the Luftwaffe largely gained air superiority while also interdicting Poland’s infrastructure, especially portions involved with mobilization, reservist assembly points and rail nodes. Sixty He 111 bombers hit Krakow on the first day while others bombed Łodz, L’wow and Lublin; thick fog prevented the Warsaw attack. Stukas (Ju 87s) and Do 17s attacked airfields at Deblin, Goclaw, Krosno, Ktowitz, Moderowski, Mokotow, Toruń, Wadowice and Warsaw‑Okęcie. They mainly destroyed older models, since as a precaution on the last day of peace, the Poles had withdrawn their best planes to scattered secondary bases. Polish mobilization stations and troop trains came under heavy bombardment, as did Polish bases and ships in the Baltic. The Luftwaffe provided close air support for the advancing army from day one. Of particular note was Generalmajor Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen’s Fliegerfuhrer zbV, made up of five Gruppen of 140 Stukas and one each of Bf 110s and Hs 123 biplanes. This outfit went on to become Flieger‑Korps (Air Corps) VIII, which along with its commander, achieved near‑legendary status throughout World War II. Thanks to its concentrated mass, it could apply close air support operationally.

Poland’s Pursuit Brigade rose up, notably over Warsaw, and scored some early victories over German Stukas and Hs 123s. The Bomber Brigade and other close air support aircraft flew to assist the army. Losses from defending Polish cities and attacking German spearheads roughly halved the Polish Air Force in the war’s first five days.

During the second phase of the war, the Luftwaffe could basically operate with impunity as the Polish Air Force retreated eastwards. Most missions were in support of the army, in particular the blitzing panzers. When the 4. Panzer‑Division reached south‑west Warsaw on 8 September, the Luftwaffe arrived in force, first to assist the division’s attacks and then to cover its defence and withdrawal. Around the 11th, however, both air forces concentrated their efforts in the region of the Bzura counterattack. After initial German surprise, the Luftwaffe arrived in force in support of the 8. and 10. Armeen. Medium bombers called off their attacks against industrial and infrastructure targets in order to contribute to the ground combat. With this crisis mastered, German planes once again helped the advancing army negotiate the Vistula River crossings.

The concentrated bombing of Warsaw marked the next phase of aerial operations. Beginning on 13 September, Luftwaffe bombers started hitting the city in earnest. After dropping millions of leaflets warning the civilian population to evacuate the city, the assault began on the 16th in concert with army heavy artillery. Large raids followed on the 18th, 19th, 22nd and 24th, as the two sides negotiated the capital’s surrender. By that point, the German high command had grown tired of Polish stalling, so ordered a massive bombardment for the 25th. More than 400 bombers flying three to four sorties dropped over 500 tons of high‑explosive and 72 tons of incendiary bombs on government buildings, water, gas and electric utilities, and military targets. Surrender negotiations began the next day and were signed on 27 September.

At a cost of 743 aircrew and 285 machines (including 109 bombers), the Luftwaffe learned some valuable lessons for the future. Air–ground cooperation was good but needed improvement. A harder to fix problem was its equipment, since from now on the Germans would have to fight with what they had on hand: Aircraft that were too small, too slow, under‑armed and with short ranges. As for Poland, many of its aviators escaped to fight another day, under more even odds."

- Robert Kirchubel, Atlas of the Blitzkrieg 1939–41, page 56

To find out more, order your copy of Atlas of the Blitzkrieg 1939–41.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment