This month sees another two titles join our Air Campaign series, ACM 3: Rolling Thunder 1965–68 delves into the campaign that was meant to keep South Vietnam secure, and dissuade the North from arming and supplying the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War. Today on the blog we welcome Richard P. Hallion, author of Air Campaign 3, as he discusses the Operation and his new book.

I. About this Book:

By the end of 1945, the world was long overdue for a period of extended peace. But instead of an era of international harmony under the auspices of the newly created United Nations, the collapse of the Axis powers fuelled big power realignments, rivalries, regional insurgencies, and general instability. From this sprang the Soviet–American post-war rivalry embodied in two major alliances, the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact and the American-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); establishment of Israel; creation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC); and a contest between East and West for influence over the post-colonial non-aligned “Third World” then coalescing around Jawaharlal Nehru’s India.

In August 1945, the age of atomic warfare dawned with the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In June 1948, an ultimately unsuccessful Soviet blockade of Berlin signalled the onset of the Cold War. Over 1949, the Soviet Union tightened its grip on Eastern Europe and detonated its first atomic bomb; China fell to Mao Zedong; and insurgencies erupted in Greece, Malaya, and Indochina. In June 1950, North Korean troops invaded South Korea, subsequently saved through a combination of dogged resistance and the United Nations coalition’s total air, materiel, and logistical superiority.

Though Western air power analysts studied Korea and other limited war contingencies, conventional-style war largely dropped from American and European public and policy consciousness, replaced by growing fears of global nuclear war. In 1953, the United States Air Force had issued Air Force Manual 1-2 (AFM 1-2) that reaffirmed the central role of strategic bombing in attacking an enemy’s heartland, and emphasized nuclear attack in future wars. Between then and 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration emphasized nuclear deterrence through a strategy of “massive retaliation.” Over Eisenhower’s Presidency, the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy acquired sophisticated nuclear-armed fighters, interceptors, bombers, and missiles; and the U.S. Army deployed atomic cannon and ballistic and surface-to-air missiles. The Soviet bomber threat—not as profound as initially thought—drove development of an air defence network of radars, specialized jet interceptors, and both surface-to-air and air-to-air missiles, some with atomic warheads. Air power was NATO’s lynchpin, with conventional ground forces effectively a “trip-wire” to trigger an overwhelming USAF and RAF nuclear response, assisted by attack aircraft from U.S. Navy and Royal Navy carrier strike forces (and, later, from Polaris-launching SLBMs operating deep at sea.)

The eight-engine Boeing B-52 Stratofortress exemplified America’s global nuclear reach;

here is a B-52H (SN 60-0006) during flight testing. Source: USAF

President John F. Kennedy ended “all-or-nothing” massive retaliation, replacing it with a doctrine of “flexible response” that stressed the continued prospect of purely conventional wars and introduced the notion of limited nuclear ones. In 1961, Nikita Khrushchev attempted to isolate Berlin. Kennedy authorized the largest deployment of aircraft and other military forces to Europe since the Second World War; again, the Soviets gradually backed down.

America faced its most dangerous Cold War test, the Cuban missile crisis, in October 1962, which brought America’s nuclear-centric military to maximum readiness, from ICBMs through tactical land-and-naval aircraft. Military resolve and diplomacy secured the withdrawal of the missiles from Cuba, bringing to a welcome close a crisis that, in retrospect, constituted the single most dangerous episode in the entire forty-year history of the Cold War.

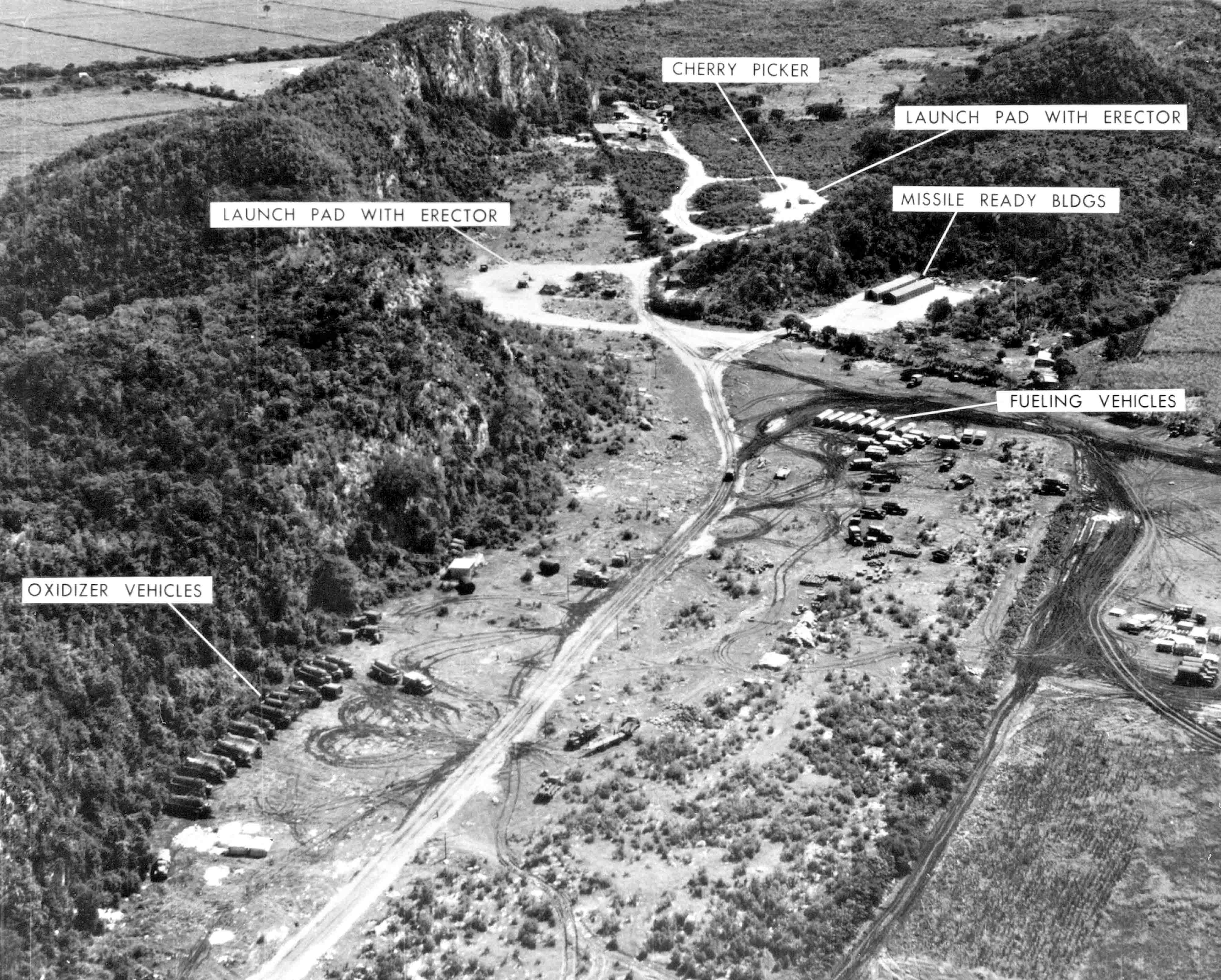

An SS-4 missile site at Sagua la Grande, Cuba, October 1962.

Source: USMC

Any relief following the Berlin and Cuban Missile crises evaporated in the face of growing insurgencies in Laos and South Vietnam. Together, they triggered a steadily expanding US commitment to Southeast Asia (SEA) that soon erupted into full-blown war.

The phrase “Vietnam War” is a convenient shorthand for what was in reality a series of interlinked conflicts. Fighting raged over South Vietnam (the Republic of Vietnam, RVN), North Vietnam (the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, DRV), Laos, Cambodia, and in Thailand. South Vietnam’s supporters included the United States, Australia, Canada, Britain, the Republic of China (ROC, now Taiwan), South Korea (the Republic of Korea, ROK), Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Spain, Thailand, and West Germany. North Korea (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK), the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Soviet Union (USSR), Czechoslovakia, Cuba, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Romania supported North Vietnam and aided communist insurgents in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

U.S. participation lasted 5,182 days—February 28 1961 through May 7 1975, over fourteen years of continuous conflict—making it America’s longest 20th Century conflict. To those who fought in Vietnam, whether on land, sea or in the air, the war highlighted serious doctrinal, training, force-structure, and technological deficiencies in America’s military machine. The war’s grim calculus of loss, disappointment, and failure has furnished fodder for military staff colleges and academies, and a plethora of post-war studies.

U.S. Army infantry searching for Việt Cộng, 23 January 1966.

Source: NARA

Just as there was no single “Vietnam war,” there was no single “Vietnam air war.” Rather, South Vietnam, the United States, and their allies operated covert air missions over Laos and Cambodia; a complex “in-country” air war across South Vietnam of reconnaissance, aerial defoliation, air transport, helicopter-based troop-insertion and aerial fire support attacks, fixed-wing battlefield air interdiction (BAI) and close air support (CAS); a littoral maritime patrol and riverine air support war; and an on-and-off-and-on-again air war over North Vietnam.

Operation Rolling Thunder (1965–1968) is at once both Vietnam’s most controversial air campaign and also the most controversial air campaign in all of American 20th Century air power history, even including the troubled early days of daylight bombing against Nazi Germany in 1942–1943. Its troubled record has subsequently shaped the theory and practice of American air war—influencing its doctrine, training, planning, and operational execution—as evidenced by subsequent American air campaigns.

In 1965, when Rolling Thunder commenced, South Vietnam faced collapse. A military coup—supported by the United States—against President Ngo Dinh Diem in early November 1963 had led to his death and created political chaos. Over the next fifteen months, DRV assistance to South Vietnamese and Laotian insurgents increased dramatically, and units of the People’s Army of Viet Nam (PAVN) crossed into Laos and the South. After sporadic retaliatory air strikes taken after several Việt Cộng and North Vietnamese actions against American and South Vietnamese forces and facilities—the Tonkin Gulf incident (Aug. 1964), and attacks on Bien Hoa air base (Nov. 1964), a Saigon hotel (Dec. 1964), the Pleiku airfield and support base (Feb. 1965), and a Quy Nhon enlisted men’s billet (Feb. 1965)—failed to curb rising Việt Cộng violence in the south, President Johnson and his senior defence team launched Rolling Thunder.

At its core, Rolling Thunder reflected both the White House and Pentagon’s frustration and increasing alarm as South Vietnam and Laos rapidly unravelled. It sought to influence the DRV’s leadership to cease their support of Việt Cộng (VC) guerrillas in South Vietnam and Pathet Lao (PL) insurgents in Laos. Thus, though ostensibly separate from the day-to-day air support war already run over South Vietnam (including reconnaissance and trail interdiction missions over northern and southern Laos and Cambodia) Rolling Thunder’s air strikes over the North were intended to influence the war’s political-military outcome in the South.

As executed, Rolling Thunder was more a series of individual operations conducted in fits and starts than a single coherent air campaign, and it suffered accordingly. An exceptional level of “out of theatre” civilian input characterized its planning, oversight, and execution. A variety of Johnson administration political leaders—as a group, both untrained and inexperienced in military strategy, operational art, and tactics, particularly air war—overturned previous national security practice by assuming direct control of individual targeting within the Executive Branch (e.g. Presidential and Executive Agency senior staff) level, based on inputs they received from U.S. Pacific Command (Military Assistance Command Vietnam, MACV; the USAF’s Pacific Air Forces, PACAF; and the Navy’s Pacific Fleet, PACFLT), and the national intelligence apparatus (the Central Intelligence Agency, CIA; the National Security Agency, NSA; and service military intelligence components). Indeed, the control of targeting largely occurred within the West Wing of the White House itself. Principle participants included President Lyndon Johnson and his senior staff, particularly National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara.

From the outset America’s uniformed military leadership—from the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) down through regional and theatre commanders—expressed reservations about the scope and intent of Rolling Thunder, as did the operational commanders and airmen under their command who were tasked with its execution. Though Rolling Thunder took North Vietnam’s leaders by surprise, very quickly DRV air defenders adapted, learning how to confront American airmen with a mix of fighters, surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and antiaircraft fire, assisted as well by sapper attacks directed against American air bases in South Vietnam and Thailand. Abroad, Rolling Thunder accelerated the growth of an international anti-war protest movement, ultimately triggering Lyndon Johnson’s decision not to run for re-election in 1968. In doing this, it changed the course of the war, which continued off-and-on until North Vietnam overran South Vietnam in April 1975.

For the airmen who flew in Rolling Thunder, the haphazard campaign with its feckless and politically charged on-again, off-again nature became an exemplar of how not to conduct an air war. It stood in sharp contrast to the use of air power in the Second World War and even Korea, and, as they proceeded through their own military service and entry into senior command, American airmen kept the experience of Rolling Thunder as a touchstone for their own conduct of future air operations, particularly Operation Desert Storm of 1991.

A flight of 355th TFW Republic F-105D Thunderchiefs air-refuelling from a Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker before ingressing into Pack 6 during 1966. The F-105D (SN 62-4228) in the foreground is Alice’s Joy, flown by 355th TFW vice commander Col. Jacksel “Jack” Broughton. Source: NARA

Colonel Robin Olds and 8th Tactical Fighter Wing “Wolf Pack” pilots and backseaters add stars indicating new MiG kills to their Club, May 1967. Source: USAF

POWs were often paraded before screaming crowds that regime cheerleaders had provoked into a frenzy, even to the point of attacking and abusing the prisoners. Enduring one sanctioned gauntlet in Hà Nội are L-R (1st row): Richard Keirn, Kile Berg; (2nd row) L-R: Robert Schumaker & Carlyle “Smitty” Harris; and (3rd row) Ronald Byrne and Lawrence Guarino; all were released in 1973. Source: USAF

II. The Author and the Book

For author Dr Richard P. “Dick” Hallion, the fiftieth anniversary of the Rolling Thunder campaign offered a unique opportunity to examine this controversial campaign in all its significant aspects, and, particularly, to highlight the fickle and even contradictory political intervention that had such a disastrous impact on strategy, operational decision-making, and day-to-day tactical operations over the North.

Though Rolling Thunder has been examined by many authors, few possess his years of study into military aviation and aerospace technology. He has been a founding curator of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, a NASA and Air Force historian, a senior issues and policy analyst on the staff of the Secretary of the Air Force, a visiting professor at the US Army’s Military History Institute at the Army War College, and the Charles Lindbergh Chair in Aviation History at the Smithsonian Institution. He is a frequent commentator on air and space technology (particularly in the field of hypersonics), and is a Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and the Royal Historical Society. As well, he has flying experience as a mission observer in several of the key aircraft of Rolling Thunder, including the F-104, F-105, F-4, and F-111, and other Vietnam-era military aircraft including the Boeing KC-135, BAe Canberra, the Cessna O-2, and Bell UH-1.

As a young university student living in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., the author witnessed first-hand how Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam policies triggered widespread campus unrest, matched by the frustration and growing anger of American airmen as they saw airpower misused and misapplied.

“Jack Broughton’s Thud Ridge was an eye-opener for me,” he recalls; “Here was one of Rolling Thunder’s most notable airmen essentially calling-out Johnson, McNamara, and the senior American defense leadership for not only mismanaging the war, but, effectively, breaking faith with their own airmen. It was just astonishingly frank, and, over the years, as I met Jack Broughton—who became a good friend—and other Rolling Thunder airmen such as Robin Olds, Chuck Horner, Bud Day, Tex Birdwell, and Bob Dunn, I quickly learned they all shared the same mixture of dismay, incredulity, and anger. (Later, H. R. McMaster—now President Donald Trump’s National Security Advisor—documented in his book Dereliction of Duty how even before Rolling Thunder the Johnson national security team had set the stage for eventual disaster.) Having examined aspects of air power in the First and Second World Wars, Korea, and in the Gulf, I saw this book as not only a logical extension of my own coverage of military aviation, but also as a duty: a necessary tribute to those who flew—and too often fell—in the skies over North Vietnam during the disastrous years that Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, and their acolytes held sway in Washington.”

Author Dr Richard P “Dick” Hallion, Seoul, Korea .

Source: RPH

Rolling Thunder 1965–68 is now available to pre-order for a discounted price until 28 February. Get your copy by clicking the title.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment