In today's blog post, Benjamin Lai looks into the Battle of Shanghai and how July 1937 marked the beginning of World War II for the Chinese. Benjamin's newest book is Campaign 309: Shanghai and Nanjing 1937, and is now available to pre-order.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the battle of Shanghai and the subsequent sack of Nanjing, the then capital of China, by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. This campaign, fought between August and December 1937, can be said to be the first large campaign of World War II. While Britain marks September 1939 as the start of their World War, for the Chinese July 1937 was their beginning; the start of eight long years of struggle between China and Japan that would only end with the dropping of two atomic bombs in August 1945. However, the animosity between these two Asian giants goes back much further to 1895 when Imperial China was defeated in the First Sino-Japanese War, a war fought largely in Korea and its surrounding waters. While Britain and Germany, once bitter enemies, have overcome haterade with friendship by linking both countries not only politically, economically but also militarily, China and Japan felt, despite ending hostilities in 1945, that there were still remaining scores to settle, much of which stems from the events of December 1937. These unsettled disputes from 80 years ago are the basis for many diplomatic tensions between modern day China and Japan.

British academic Rana Mitter described China as the “Forgotten Ally” in World War II. Most Western narration often omits battles that occurred in China, concentrating instead on events in Burma and battles of the carriers in the Pacific. The upcoming Osprey Campaign book: Battle of Shanghai and Nanjing 1937: The Massacre on the Yangtze, hopes to redress this by offering a comprehensive English-language guide to this momentous battle; a battle involving all three services, air, land and sea, described by some military historians as the forerunner to the battle of Stalingrad in 1943. This campaign saw the destruction of the Chinese “New Model Army”, a German trained and equipped force complete with Mauser Rifle, stick grenade and M1935 “Fritz helmet”. Despite support from battle-hardened German advisors; poor tactics and unevenly matched weaponry were no match against a professionally trained Japanese force equipped with the latest guns and planes, despite overwhelming manpower.

This book also looks into a rarely discussed aspect of the war, the political intrigue and service rivalry between the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy that contributed to the reasoning behind the war in Asia. While the motivation for war in Europe was very much the decision of one man, Adolf Hitler, in Asia, the start of WWII in was not the action of the collective decision of the state, but a by a small group of ultra-nationalist military officers hell-bent on military action, not only as a mean for career advancement but also as a bargaining tool for bigger military budget. Their extremist views and sense of racial superiority over the Chinese meant they saw the war in China as, not only the right thing to do for the development of Japan, but also a crusade to bring civilisation to the uneducated. The battle of Shanghai was initiated by the Japanese Navy as a response to the army’s northern China campaign. For years, the army had been getting rich from Manchuria and the navy wanted a piece of their own war in China.

Shanghai was the perfect place to launch it, featuring a vast river network as well as a large naval garrison. Furthermore, Shanghai was only 678 miles from Kure, the key navy base in Japan making logistics simple and convenient. To start a war, one needs a casus belli; the army’s war in the north was initiated over the Marco-Polo Incident, in Shanghai the navy’s excuse was the shooting of a Japanese marine sedan who failed to stop at a regular Chinese roadblock just outside the Chinese military aerodrome.

Another unique characteristic of the war in Asia rarely discussed is the fact that many of the military decisions made by the Japanese were made by local officers, often in direct violation of imperial orders from Tokyo. Not only was the battle in Shanghai very much masterminded by a few navy hawks, the subsequent enlargement of the battle to Nanjing was done against specific orders. The imperial order no. 600 issued to General Matsui Iwane clearly stated that the limit of exploitation was to be no further west of Suzhou, a picture postcard ancient city not unlike Venice, some 136 miles east of Nanjing. The tail was wagging the dog: Japan was out of control.

After the capture of Nanjing in mid-December 1937, the victorious Japanese Army went on an rampage: raping, pillaging and killing POWs and civilians under the pretext “too many prisoners to handle”. At the Tokyo War Crime Trial, Matsui tried to escape blame by saying that he, as overall campaign commander, was not responsible for army discipline, only on operational matters. However, his excuse was quickly silenced when the prosecutor took out a copy of the written order for the attack on Nanjing where Matsui specifically instructed his army: “to reduce contact with Chinese civilians”. However, during the attack, Matsui was sick and largely bedridden and the operation was placed in the hands of Prince General Asaka Yasuhiko, Matsui’s second-in-command. Asaka’s status as a senior member of the Imperial Japanese Royal house as the uncle of Emperor Hirohito may have something to do with the fact that Matsui did not remonstrate with his subordinate on the ill behaviour of the troops. During an era where the word of a Royal family member still holds supreme, getting into an argument or upsetting a Royal prince of this seniority would be detrimental to one’s career. As a mark of displeasure, the Imperial HQ in Tokyo recalled both Asaka and Matsui to Tokyo in early 1938. Both would have no further operational roles, Matsui chose to retire and Asaka took up a cushy post in the military council.

Many of the key incidents of the battle of Shanghai and Nanjing occurred within the urban area of the two cities and can be easily reached by taxi or the Metro. For those who have the opportunity to visit China and if time allows, take a day out to visit some of the places mentioned in this upcoming book, you will be pleasantly surprised to see how much history can still be seen 80 years on.

Read more on the Imperial Japanese Army's assault on China in Campaign 309: Shanghai and Nanjing 1937. Click here to pre-order today!

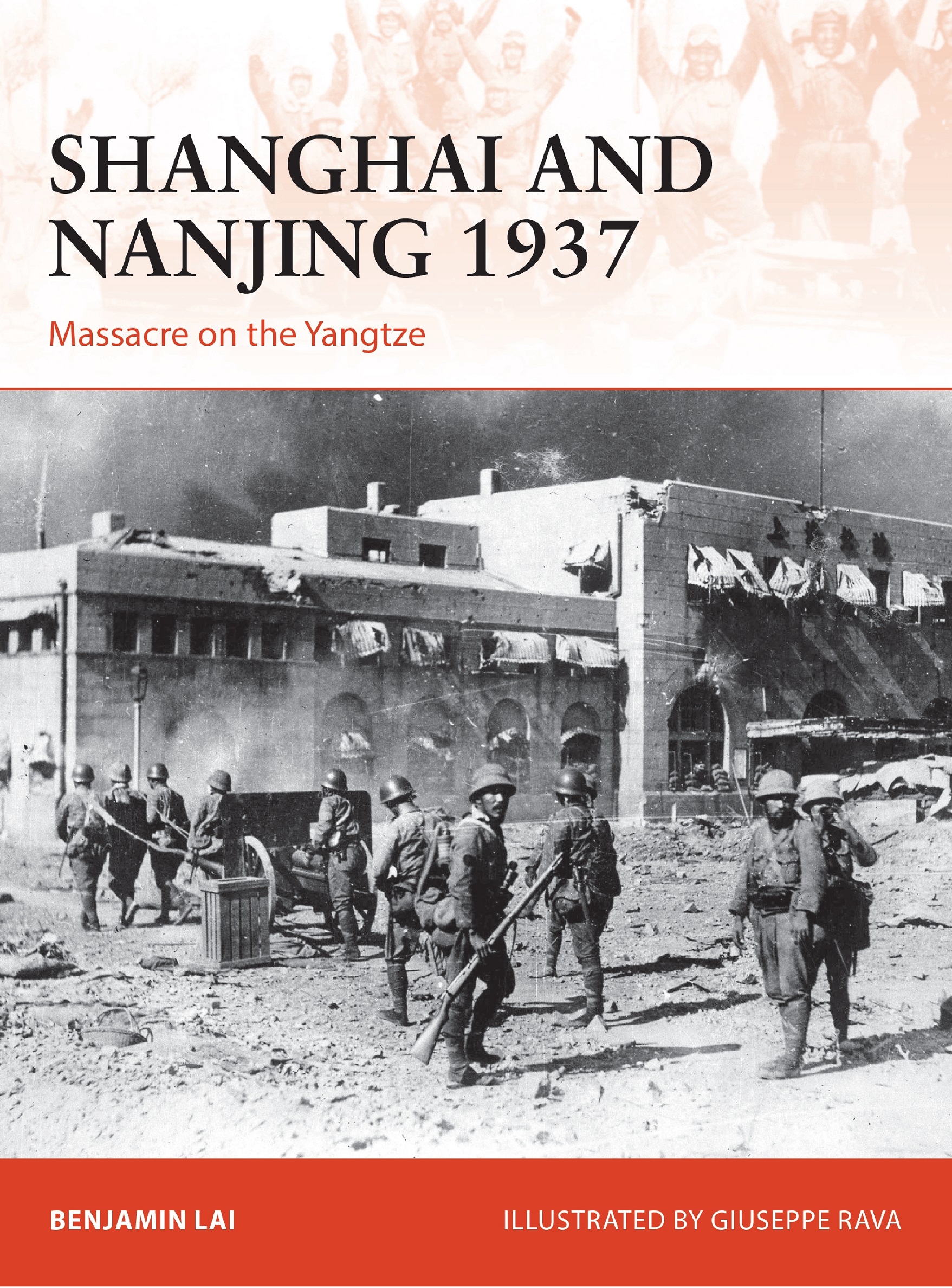

The Imperial Japanese Navy Special Naval Landing Forces troops in gas masks prepare for an advance in the rubble of Shanghai, China. (Source: Wikipedia)

The Imperial Japanese Navy Special Naval Landing Forces troops in gas masks prepare for an advance in the rubble of Shanghai, China. (Source: Wikipedia)

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment