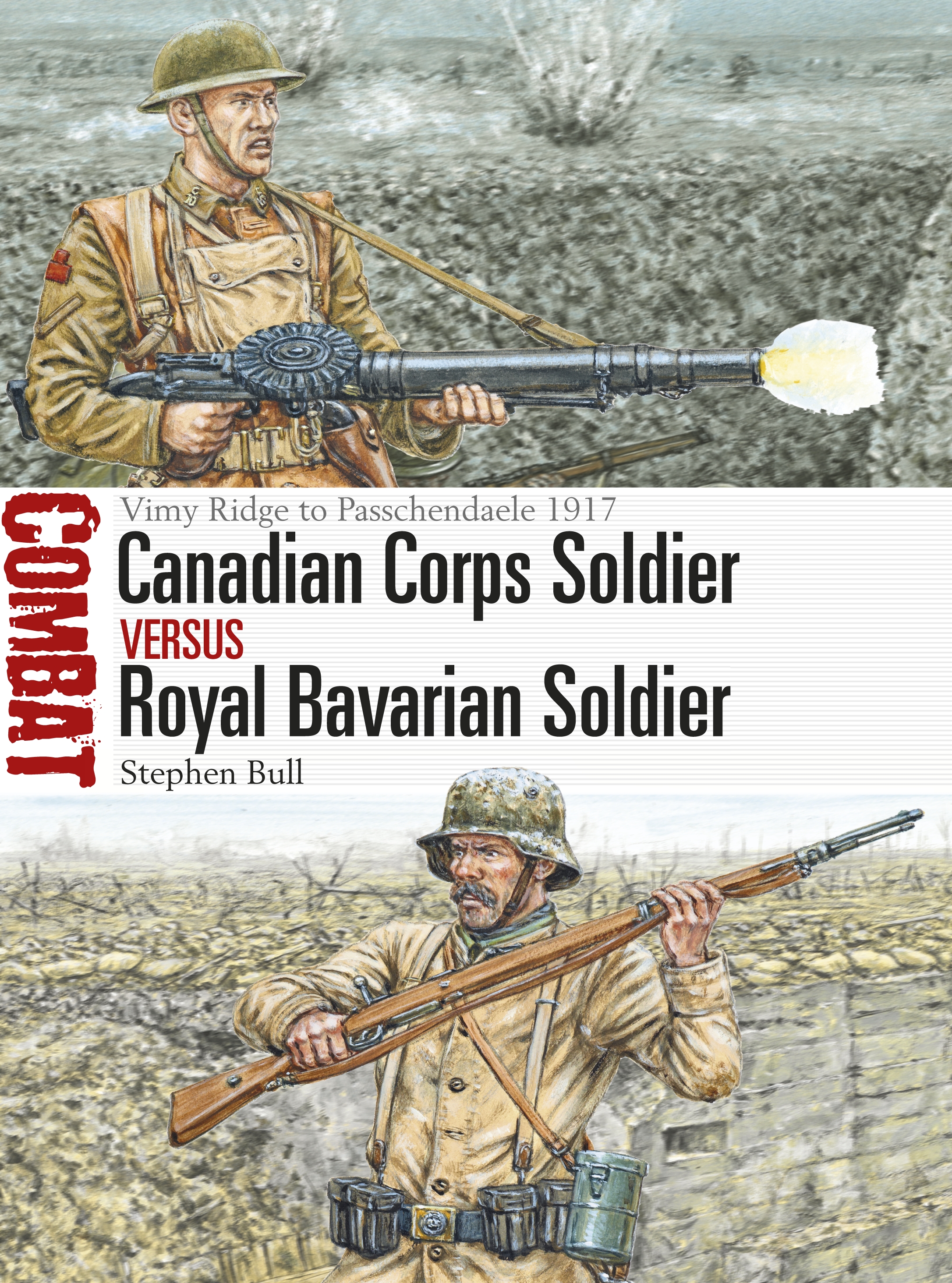

This month sees the release of Combat 25: Canadian Corps Soldier versus Royal Bavarian Soldier by Stephen Bull. The latest addition to our Combat series focuses on the three notable encounters between the Canadian Corps and the Royal Bavarian Army during World War I: the Canadian storming of Vimy Ridge, the engagement at Fresnoy, and the infamous battle of Passchendaele in 1917. Below is an extract from the book, which is now available to pre-order ahead of its release next week.

ORIGINS AND RECRUITMENT

Canadian

Canada made no decision to enter World War I. Instead she was informed by telegraph, that, being part of the British Empire, as of 4 August 1914 she was at war with Germany. Nevertheless, initial reactions were mainly enthusiastic, with the Governor General, HRH Prince Arthur Duke of Connaught, quickly cabling back to London that many would immediately volunteer for active service. This positive news was tempered with the codicil that ‘When [the] inevitable fact transpires that a considerable period of training will be necessary before Canadian troops will be fit for European war, this ardour is bound to be dampened somewhat’ (Nicholson 1962: 11).

The reason for the Governor General’s prognostication was simple. While Canadians showed a sense of patriotism typical of the age, and the country had both resisted aggression from her US neighbour and sent men to the Second Anglo-Boer War in the past, hers was fundamentally a non-military society. There were 8 million Canadians, spread over 3.7 million square miles: yet as of March 1914 there was a permanent military establishment of just 3,000. The vast majority of Canadian troops were ‘Militia’, a part-time force supposed to comprise 5,615 officers and 68,991 NCOs and men, but whose actual strength was somewhat lower. City units performed 16 days’ training of which four were in summer camp; rural units conducted 12 days, all of them in camp. The yearly budget for all forces, stores and buildings was less than C$11 million, of which about 15 per cent was spent on the annual drill. True, Sir Ian Hamilton, Inspector General of Overseas Forces, had recently recommended a reorganization on a ‘divisional’ basis, and 200 artillery pieces were held in readiness, but virtually all else was lacking. There were not enough uniforms, and the Militia were expected to provide their own boots, shirts and underclothing.

'Fight for a pillbox' at the attack on Bellevue, 1917.

'Fight for a pillbox' at the attack on Bellevue, 1917.

This meant that when Canada went to war, and an offer was made for a force to proceed to Europe, an initial target of just 25,000 men was set for this first contingent of the CEF. The Adjutant General approached Militia units direct for lists of volunteers, aged from 18 to 45, meeting physical requirements, general proficiency, and with a high standard of musketry: reserve officers and men with previous experience could be included. This scheme foundered in confusion, and in a swift about-face the call was readdressed to districts, asking them to supply specified numbers. Districts in turn approached units for quotas, and the men mobilized at Valcartier near Quebec City during late August and September 1914.

CEF battalions varied in constitution, but the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) may be used as a not untypical example. Into a new block of regimental numbers (27001–28500) were dropped approximately 970 volunteers of the Militia from the 48th Highlanders. These were topped up with men of the 97th Algonquin Rifles, the 31st Gray Regiment, and others. Though officially the minimum height was 5ft 3in and the age limit 45, the 48th Highlanders’ commanding officer set a more stringent 5ft 8in, and 30 years. On arrival at Valcartier, the troops appeared ‘fully equipped with the exception of rifles, knapsacks and bayonets, free of expense. Uniforms were provided by the Regiment’ (Beattie 1932: 21). Initial recruitment literature referred to the new body as an ‘overseas company’ of the 48th, and the regimental crest, Davidson tartan, Glengarry cap and other Highland distinctions were retained. Regimental moustaches were demanded, and in the winter of 1914/15 youngsters made manful, if sometimes unsuccessful, attempts to grow them.

Only with the passage of time, casualties and replacements would the Toronto character of the 15th Bn gradually recede into something more broadly ‘Canadian’. At the war’s end men who between them had histories with more than 60 different units would be found in the ranks of the 15th Bn. A key exception to this sort of recruitment pattern was the battalion raised by Capt Hamilton Gault, a Montreal veteran of the Second Anglo-Boer War, who neatly sidestepped procedure, offering to raise a unit of ex-soldiers and to contribute to its cost. This unit, Princess Patricia’sLight Infantry, landed in France on 21 December 1914, eight weeks before 1st Canadian Division was committed.

As the war evolved, so did Canada’s contribution. By late 1916 Canada had 100,000 men in four divisions in the field and voluntary recruitment trailed off. In November 1916 the controversial and ambitious Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes, was finally jettisoned amid recriminations for his eccentric equipment policies, his efforts to establish a separate Canadian military command structure, and his dangerously impolitic stance on French matters. In late October 1917, Canada followed Britain in introducing conscription, but the Military Service Act met with a very mixed reception, and was opposed by many French Canadians. In the event about 100,000 men were conscripted, but of these barely half would make it overseas before the end of the war.

The average Canadian recruit was of better physical stock than his British or German counterpart: the proportion of men working on the land in farming, hunting and forestry was significant. The impact of this was not as great as might be expected, however, for recruitment was most successful in cities. Moreover, many recruits – and a majority of the first 30,000 – were born in Britain: Fred Bagnall, referring to the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment), recalled that the first three companies of his unit maintained affiliations with different parts of the UK (Bagnall 2005: 15). Attempts were made to convince the 14th Bn to don the kilt, so completing a ‘Highland Brigade’, but with the 14th Bn being ‘grenadiers’, ‘riflemen’ and French Canadian infantry, they adhered steadfastly to trousers. British predominance persisted among the fighting battalions in France. For example, almost half of the 58th Battalion, which crossed to Europe in November 1915, was still composed of Englishmen, with a good number of others of Irish, Scottish and Welsh birth. Some were from other parts of the Empire, and there were 16 Americans. Just a third of the men were Canadian-born, and many of these had British parents or grandparents.

Bavarian

Unlike Canada, Bavaria had many centuries of martial tradition, and an established system of conscription. Under recent Imperial law the kingdom was bound to provide 11 per cent of the manpower of the German Army, a figure proportionate to her population. As with troops of the other German states, men were liable for service first in the Stehendes Heer (standing army), before passing into the Reserve, the Landwehr and finally the Landsturm (see Bull 2014: 12–13).

Bavaria was not only a kingdom with its own War Ministry in 1914, but its troops were still referred to as the ‘Royal Bavarian Army’. It numbered its regiments in a separate sequence, and boasted an Infanterie-Leib-Regiment (infantry bodyguard regiment). Its infantry regiments possessed distinctive Fahnen, or colours, bearing the arms of Bavaria and bore honour titles of significance to Bavarian history. The peacetime army was organized in six consecutively numbered divisions, based at Munich, Augsburg, Landau, Würzburg, Nuremberg and Regensburg, with brigade and regimental headquarters in these and surrounding localities. This strength more than doubled in war with the embodiment of the Reserve and the addition of Ersatz or supplementary units and the Landwehr. A total of 23 Bavarian divisions were raised by the end of the war, plus the Alpenkorps, which was largely Bavarian in composition.

The Bavarian Army had an effective strength of 87,214 all ranks in July 1914, but while units on home soil remained under control of the Bavarian War Ministry, supreme command of the Bavarian field army passed to the Kaiser. The force was initially bolstered by the addition of two divisions recruited in Western Germany, and fought in the ‘Battle of the Frontiers’ in 1914 as 6. Armee under Crown Prince Rupprecht. Though subsequently 6. Armee continued to exist and Rupprecht was promoted to Generalfeldmarschall, his command ceased to be essentially Bavarian, and Bavarian divisions now fought alongside formations from all parts of the German Empire.

Pre-war recruit quality was high, being maintained at least in part because only a proportion of eligible men were taken for the Army after the yearly mustering at which they were medically examined and documented. In wartime, expansion of the Army by embodiment of the Reserve and Landwehr regiments mopped up previous years’ harvests of trained men, and soon the pool of Landsturm personnel was being dipped into. Volunteers, who initially came forward in large numbers, began to dry up, and though the majority maintained good levels of commitment the sky-high morale and the ‘spirit of 1914’ was gradually blunted by the lengthening conflict. Allied blockade put pressure on the supply of materials and food, though arguably rural Bavaria was better placed than major industrial areas to face hardship.

Canadian Corps Soldier versus Royal Bavarian Soldier is now available to pre-order by clicking here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment