- In a nutshell, what were the Italian Wars of Unification? Why did they begin?

Well, in a few words we could describe the three Wars of Italian Unification as the military conflicts that led to the formation of modern Italy as a unified nation. They consisted of large military confrontations between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia (also known as Piedmont), the leading force of the Italian unification from a political and military point of view. Primarily the Wars of Unification were wars of liberation, because their main objective was that of freeing northern Italy from the foreign presence of the Austrians. After the Congress of Vienna (1815), the Austrian Empire had started to control Lombardy and Venetia, thus breaking again that partial political unification that Italy had achieved during the Napoleonic period. Many aspects of the Italian Wars of Unification are examples of “romantic” war fought during the period 1815–1870: a triumph of emerging national identities and middle-class ideals. This process, known in Italy as “Risorgimento”, lasted several decades and in these books I focus on the most decisive part of it, starting in 1848 and ending with the final unification of Italy in 1870. Explaining the causes that led to the Italian national resurgence in a few words is not easy, to sum up we could say that the Napoleonic era had gradually increased the sense of patriotism in all Italians and that after the Congress of Vienna, Liberal ideas had become dominant in the peninsula. As a result the middle classes of all the Italian states started to fight for the unification of Italy and for total independence from Austrian influence. Something similar happened in various other European states of the period: Germany, Hungary, Poland, Greece, Belgium and others. After all the Europe that we know today was forged during post-Napoleonic 19th century.

- How did you decide to focus on this topic?

My primary objective since becoming an Osprey author for the Men-at- Arms series has always been that of covering little known armies and conflicts. That is why I started by writing books on the wars of Latin America, which had been requested by readers for some time. When I decide to propose a topic for a book my choices are always strongly influenced by the request of the readers. The Men-at-Arms series is a very large one, with an impressive backlist of more than 500 titles: some may think that finding new topics for it could be difficult, but here are so many gaps to be filled and that is exactly what I always try to do. The armies of the Italian Risorgimento were probably one of the biggest gaps to be covered regarding 19th century history, since I had all the needed competence and information to write about this topic, I decided to propose it to the Men-at-Arms’ series editor Martin Windrow. He was very enthusiastic about the idea from the beginning, so we decided to go on with it by splitting the idea into two titles. The amount of information that I have on the military history of the Italian Wars of Unification is incredibly vast, so we needed the space of at least two books. In any case, it was terribly difficult to concentrate everything into such a small space. However, I think that nothing important has been missed.

- This is the first in a series, was there any particular reason why you chose to focus on Piedmont and Naples first?

In total the series will cover the armies of eleven different states, plus the volunteers of Garibaldi, Piedmont, Naples, Papal States, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, Duchy of Modena, Duchy of Parma, Kingdom of Sicily, Provisional Government of Lombardy, Republic of San Marco, Roman Republic and Central Italian League. The first six were the original Italian states that existed before the revolutionary events of 1848–1849, the following four were created by the Italian patriots during the turbulent political events of 1848 (they were short-lived revolutionary states) and the Central Italian League was a temporary confederation created soon after the end of the Second War of Unification (1859). Finally, Garibaldi’s volunteers had a long history: from the “Italian Legion” of 1848 to the “Cacciatori delle Alpi” of 1859, then the famous “Red Shirts” of 1860 and the “Corpo Volontari Italiani” of 1866. Considering this incredibly vast amount of content we had to divide the 12 military forces in some way. I decided to do this according to the amount of information available for each of them, so the two military powers of Italy were assembled together in the first volume. Piedmont had the best army of the Italian peninsula, an elite force that was capable of confronting a major European military power like Austria. Naples (the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies) had a very large army composed by a large number of different troop types (all with peculiar uniforms). So it was absolutely necessary to have a large amount of space to cover these two armies in an effective way. I would like to add that this first book will also cover the Italian Army during its first years, from 1861 to 1870. I will analyze the gradual transformation of the Piedmontese Army into the Italian one, describing the first combat experiences of the latter (Third War of Unification against Austria and the fight against Brigandage). Just a final note regarding Brigandage, very few people outside Italy probably know that during 1861–1870 the Italian military forces were heavily involved in a harsh counter-guerrilla conflict in the southern part of the peninsula, against violent bands of insurgents financed by the Bourbons of Naples (just expelled from their ex-realm). In the first book of the series there will be some space to discuss this.

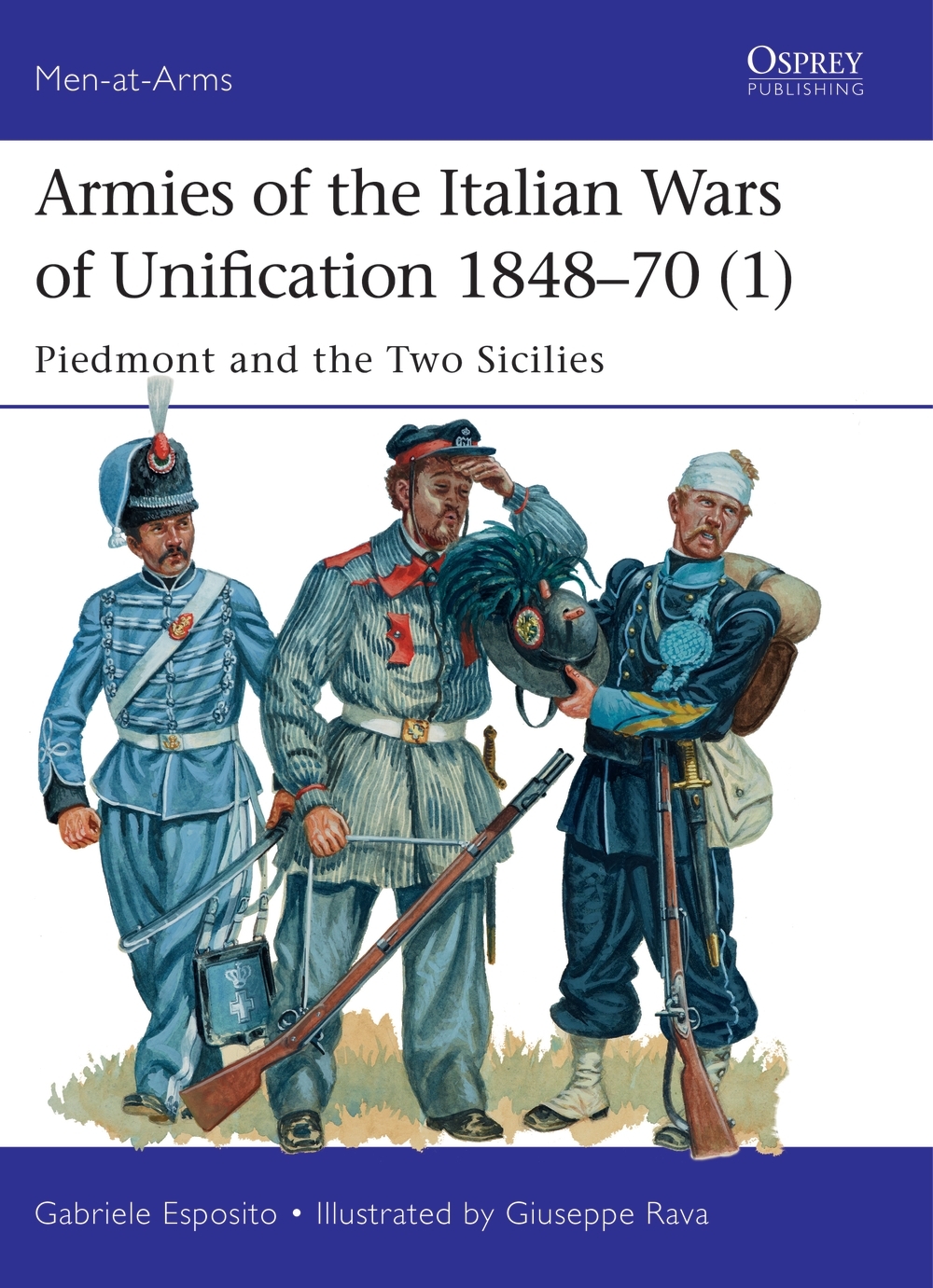

Soldiers and an Officer from the Neapolitan and Sicilian Armies, 1848

Soldiers and an Officer from the Neapolitan and Sicilian Armies, 1848

- These two armies would later turn against each other, why is that?

Yes, this happened in 1860–1861. After victory in the Second War Unification, Piedmont was able to occupy most of Italy and only the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies remained independent, under the Bourbons of Naples. Cavour, Prime Minister of Piedmont, needed a “casus belli” in order to attack the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, he had already annexed Lombardy and most of central Italy, so a large direct attack under the eyes of the European powers had to be avoided. As a result, the Piedmontese decided to leave the initiative in the hands of the greatest Italian patriot, Giuseppe Garibaldi. He landed in Sicily with just 1,089 volunteers and was soon able to defeat the Neapolitan soldiers in several clashes. The population of the island soon acclaimed him and thus the initial “Red Shirts” were soon augmented with the inclusion of hundreds of new volunteers. At this point, with Sicily in the hands of Garibaldi, the Piedmontese government started to provide official support to the Red Shirts. The expeditions of reinforcements and supplies coming from the north decisively helped Garibaldi in his conquest of southern Italy, which culminated with his great victory of the Volturno River (a battle that was fought a few miles from where I live). At this point the Piedmontese sent their army across the Papal States, in order to close the match with the Bourbons. The Neapolitan Army was then besieged in its last stronghold of Gaeta, whose conquest by the Piedmontese finally led to the birth of modern Italy. After all the Piedmontese and Neapolitan military forces fought against each other for just a few months during the siege of Gaeta, but this were extremely important for the history of Italy and ended with Piedmontese triumph.

- There were three major wars involved; will this series cover each specifically? How is this broken down in the book?

Our series is formed by two Men-at-Arms books, so it is not specifically devoted to the analysis of conflicts. As I described before, the structure and contents are based on armies and not on conflicts. In any case all three wars will be covered with a general overview, which is absolutely needed if we want to understand the military history of the Risorgimento. For this reason we have included a large and detailed chronology covering the period 1848–1870. The first book will detail the years of the First War of Unification (1848–1849); the second one will cover the final half of the chronology, with the events of the Second and Third Wars of Unification (respectively 1859 and 1866). All the significant events between one conflict and the other, however, are covered. The First War of Unification was fought in every corner of Italy and saw the involvement of thousands and thousands of volunteers. It ended in 1849 without achieving major political results, but it had created the basis for the future victory of the Italians. The Second War of Unification, thanks to the decisive military support of France, was the conflict that effectively won Italy its independence from Austria. The Third War of Unification, instead, was extremely negative from a military point of view but quite positive from a political one. The young Italian Army was defeated by the Austrians at Custoza, but the alliance of Italy with Prussia led to the liberation of Venetia from Austrian rule. The Risorgimento was a long struggle for freedom, characterized by great acts of heroism. I hope that my readers will enjoy reading about it as much as I enjoyed writing about it.

- You’re currently working on the second part of this series, which armies will this look at?

I’ve concluded writing the second book a couple of days ago. It will cover the following states and their relative armies: Papal States, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, Duchy of Modena, Duchy of Parma, Kingdom of Sicily, Lombard Provisional Government, Republic of San Marco, Roman Republic and Central Italian League. In addition, there will be large portion dedicated to Garibaldi’s volunteers. The Papal States were a medium military power in Italy, since their armed forces were not as small as those of the other states from central Italy. In addition, the Pope could count on large numbers of volunteers who came from several countries of Europe to protect the Papal States. The Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Duchies of Modena and Parma had smaller armies, mainly performing police duties, after all these states did not need large military forces, because they were ruled by minor branches of the Habsburg family and thus could count on the protection of the large Austrian Army. The uniforms of these little armies, however, were extremely interesting from the uniformologist’s point of view. The military forces of the four revolutionary states formed during 1848–1849 (Kingdom of Sicily, Lombard Provisional Government, Republic of San Marco and Roman Republic) have never been studied before in English, volume two of our series will cover all of them, with great detail. The same can be said for the army of the Central Italian League, a military force that is barely known to anyone other than Italian specialists. Finally, Garibaldi’s volunteers will be presented with great accuracy: from the first unit created in 1848 to the large corps of “Volontari Italiani” (Italian Volunteers) that fought in 1866 against the Austrians.

I’ve concluded writing the second book a couple of days ago. It will cover the following states and their relative armies: Papal States, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, Duchy of Modena, Duchy of Parma, Kingdom of Sicily, Lombard Provisional Government, Republic of San Marco, Roman Republic and Central Italian League. In addition, there will be large portion dedicated to Garibaldi’s volunteers. The Papal States were a medium military power in Italy, since their armed forces were not as small as those of the other states from central Italy. In addition, the Pope could count on large numbers of volunteers who came from several countries of Europe to protect the Papal States. The Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Duchies of Modena and Parma had smaller armies, mainly performing police duties, after all these states did not need large military forces, because they were ruled by minor branches of the Habsburg family and thus could count on the protection of the large Austrian Army. The uniforms of these little armies, however, were extremely interesting from the uniformologist’s point of view. The military forces of the four revolutionary states formed during 1848–1849 (Kingdom of Sicily, Lombard Provisional Government, Republic of San Marco and Roman Republic) have never been studied before in English, volume two of our series will cover all of them, with great detail. The same can be said for the army of the Central Italian League, a military force that is barely known to anyone other than Italian specialists. Finally, Garibaldi’s volunteers will be presented with great accuracy: from the first unit created in 1848 to the large corps of “Volontari Italiani” (Italian Volunteers) that fought in 1866 against the Austrians.

Men-at-Arms 512: Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1) is now available to order from our website, to order click here, and be sure to look for Gabriele's upcoming titles Armies of the First Carlist War 1833–39 and Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (2): Papal States, Minor States & Volunteers.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment