Writing the text

I have talked about just about everything which goes into writing a New Vanguard: defining the scope, doing the research, picking the subjects for the plates, and preparing the artist’s brief. Except the most important bit: actually writing the book.

If you are a writer (or know one) you will be unsurprised. Writers are famous (or if you are an editor, infamous) for putting off writing. Publishers and editors have a real problem when a really popular author puts off writing. Douglas Adams (Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Universe) was always notoriously late, but nothing could be done because there was only one Douglas Adams.

Fortunately for Osprey I am just a mid-list author. I have to deliver. (Besides, they offer a bonus for early delivery. As Samuel Johnson once wrote, ‘No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.’ Offer me money to be early, and I am there.)

My hero - Samuel Johnson

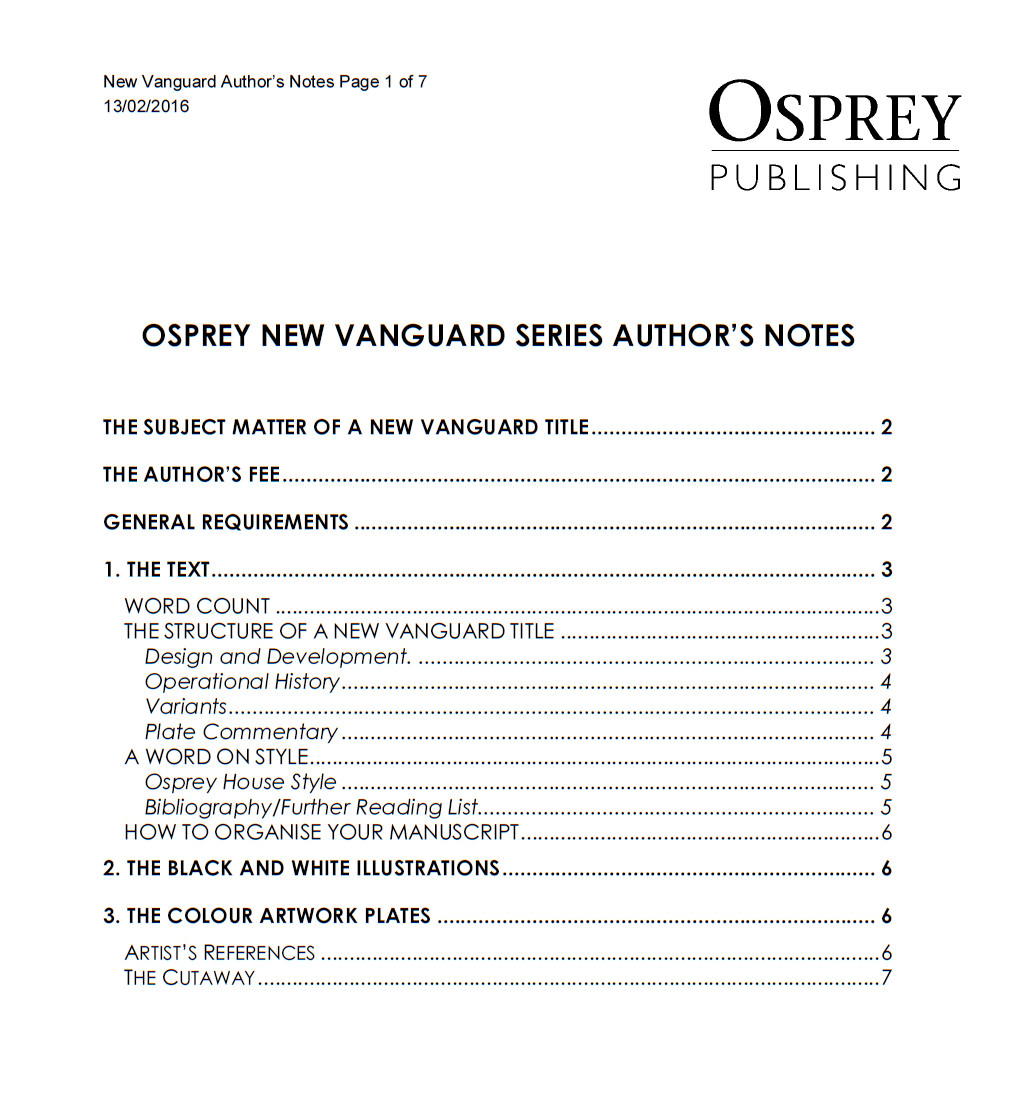

I start by developing an outline. Actually Osprey gives me an outline, sort of. Every Osprey series has a set of Author’s Notes. In it, usually the second thing listed in the General Requirements is something called ‘The Structure of a New Vanguard Title’. That is my outline. It dictates three major sections, which are to be roughly equal in size: 1. Design and development, 2. Operational history, and 3. Variants.

If you have purchased any other New Vanguard I have written you have noticed the Design and Development and Operational History sections, but may be wondering what happened to Variants. Instead there is a Ship History section. That is because I generally write about ship types in which Variants tend not to be relevant or interesting. With aircraft, armored vehicles, or artillery pieces production runs tend to number in the hundreds (or thousands), and variants are part of the story.

Here is my outline - The Author's Notes

I have written about ship categories with relatively small runs – perhaps three dozen maximum. What happens to individual ships is more interesting than their variants. I negotiated to replace Variants with Ship Histories. My editors feel spending a third of the book telling people what happened to individual ships will draw more readers than describing their use (as a category) as receiving ships, supply hulks, or school vessels. If I ever did a book covering hundreds of similar ships (for example US Flush Deck Destroyers) I would use Variants instead of Ship History.

Then I break the three broad sections into subsections. With World War I Seaplane and Aircraft Carriers Design and Development was divided into four subsections: Royal Navy, Central Powers, Mediterranean Powers (France and Italy) and ‘The Rest’ (Russia, Japan and the US). Operational History was similarly broken into 1914‒1915, 1916‒1917, 1918, and Afterward. Ship Histories (titled Ships) was divided by individual navies.

I also carve out a short section to introduce the subject. In American Medium and Light Frigates, I opened by describing the battle between Chesapeake and Shannon. In Great Lakes Warships I opened with an observer in the 1880s viewing the hull of New Orleans, a ship-of-the-line built during the War of 1812 on Lake Ontario. Both helped defined the ships covered in the book. My introduction shapes reader expectations. I now have my outline.

Eugene Ely was the first man to take off or land on a ship – a good subject for the introduction

Next I allocate word count. Osprey authors live and die by the word count. Deliver within word count or your manuscript is rejected and gets returned for revision. Some variation is accepted. Stay within 500 words of the contracted word count and the editors are happy.

A New Vanguard has a word count of 16,000. The guidelines call for 2,000 to be allocated to plate descriptions and 1,600 for photo captions. That leaves 12,400 for the main body. I reserve 400 for my introduction. This leaves between 3,600 and 3,700 words for each section. Normally I allocate 3,700 to two sections and 3,600 to a third. (How much depends upon the book. In this case, I initially allocated 3,700 words to Design and Development, with Operational History getting 3,600.)

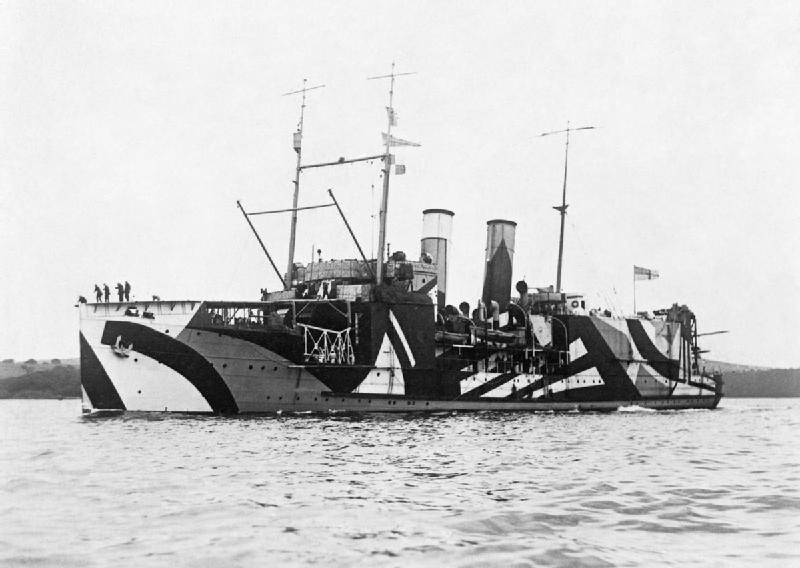

From there, the next job is to allocate a word count to each subsection. Not all subsections are the same length. In this book I allocated 1,500 words to the Royal Navy in Design and Development, but only 700 to the Central Powers. Why? Because the Royal Navy had almost as many seaplane and aircraft carriers (and different designs) than the rest of the world put together.

I wrote more about Royal Navy seaplane carriers because they had so many. This is HMS Pegasus

| Previous: The Cutaway |

Next: Putting Text to Paper |

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment