Let's Talk Plates

Writing for Osprey is like writing for Playboy. Everyone talks about the great writing, but every author knows the real reason folks buy: the pictures. In the case of Osprey, it’s the original artwork plates.

Obviously, the artist, not the author, plays first violin. That is okay. My ego can take it. I played viola back in high school. I am used to playing backup. But less well known is the fact that the artwork does not spring from the head of the artist, like Athena from Zeus. The artist creates the plates from a set of instructions called an artist’s brief. This is composed by the author.

Creating an artist’s brief is simultaneously terrifying and exhilarating.

A New Vanguard has seven plates. Authors get specific requirements for the plates. There is always a cutaway. It presents the interior of the system featured in the book. (A ship for this book. Obviously.) Of the other six plates, two are usually battlescenes, at least two are profiles, and the other two can be more profiles, extra battlescenes, or technical scenes. It depends on the subject.

[Editor’s note: ‘Almost always a cutaway’. We resisted the temptation to do a cutaway in NVG 150, for example.] [Author’s note to Editor’s note: Ewww!]

The profiles are side, top, (and sometime) front views. It is not a New Vanguard without profiles. Battlescene plates depict the featured item in combat. The technical plates are a grab-bag for “draw something cool and interesting.”

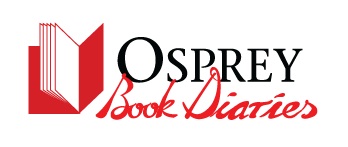

In my first New Vanguard, American Heavy Frigates, one technical plate was the gun deck of the Constitution. I reprised that idea in Ships of the American Revolutionary Navy with the gundeck of a Revolutionary War frigate. Why? To reward readers who bought both books by showing them how a frigate’s main battery had evolved.

In another book, I included a technical plate showing one quarterdeck gun position of an American frigate in 1799 and 1812. Same position, but the gun changed from a long gun to a carronade, and planking replaced weathercloths. Again, it was my opportunity to show system evolution.

Remember this?

Remember this?

Each plate requires a set of instructions, the magic “artist’s brief;” a written description of the plate to be painted; and a full set of the images the artist needs to make the artwork. Authors are expected to provide the artist with illustrations of every detail to be painted: weapons, uniforms, paint schemes, engineering drawings of aircraft, vehicles, or ships – and the terrain, when applicable. I even find the lighting conditions at time the plate occurs, the phase of the Moon, and the angle and elevation of the Sun and Moon when applicable.

I do not know how other Osprey authors package their artist’s briefs, but I deliver three sets of files:

1) A text document with the instructions – either .docx or .doc format.

2) A set of PowerPoint files, one for each plate, BEV, map or whatever.

3) PDFs, created from the PowerPoint presentations (again one for each piece of artwork).

I hear the groans. Mark Lardas is a PowerPoint ranger. He gives the artist a PowerPoint presentation. How déclassé.

Well, it is not exactly a PowerPoint presentation. It is a PowerPoint file (or maybe an OpenDocument Presentation file, if Microsoft continues annoying me), not a presentation. And obviously, you need to make sure PowerPoint doesn’t alter the proportions of the image. Otherwise the artist will think that that’s how it’s supposed to look.

It is intended to be printed out, and I do not use the itsy 4:3 default size. I set the file to A3 paper (a nod to Osprey’s European location – otherwise I would choose tabloid). We are talking a healthy size. (I would choose A1 or A2, if it were not for the inconvenience of handling printed sheets that size. Plus I know standard color printers can handle A3 or tabloid paper – mine can.)

Everything organized where I can find it

Everything organized where I can find it

There are several reasons I do the graphic images digitally using something like PowerPoint. It lets me mash different elements together. (You will see examples later.) I can store everything in my computer instead of on my desk. (You don’t want to see my office. It looks like a bomb exploded in a bookstore.) Scanning allows me to capture the visual information I find in those interlibrary loan books I get. Once an image is scanned, it is as easily added to a PowerPoint presentation as printed separately.

More importantly, I can deliver everything electronically. In the Cretaceous Age when I was first writing for Osprey I had to mail the artist’s brief. From Texas to Oxfordshire. It was expensive (some early artist’s briefs weighed over two pounds). Also, it delivered my one-and-only copy to the tender mercies of the US Postal Service and the Royal Mail.

One time, Royal Mail must have used one of their old 18th-century mail coaches – the ones pulled by horses. My tracking slip indicated the USPS delivered it to London 32 hours after I mailed it (pretty good, I thought). Then it took fourteen additional days to wander from London to Oxford. (After that I used overnight services.)

How my artist’s brief seemingly used to reach Osprey

How my artist’s brief seemingly used to reach Osprey

So, all hail electronic delivery! I may write about the 18th through 20th centuries, but I am glad to live in the 21st century.

| Previous: Back to Work | Next: Some dazzling profiles |

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment