On 26 September 1918 the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was launched. It would be the greatest American battle of the First World War, and after the armistice had been signed Field Marshal von Hindenburg wrote that 'the American infantry on the Argonne won the war'.

Below is a description of the 33d division's attack on the Hindenburg line on 26 September 1918, launched as one of the initial attacks of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. It was taken from Warrior 79: US Doughboy 1916-19, written by Thomas A Hoff.

The plan called for III Corps to advance along the left bank of the Meuse, and to push on towards two objectives. Forming up during an artillery barrage on the night of the 25th, the 66th Brigade, which contained the 131st and Kurt’s regiment, the 132d, prepared to go over the top. The sector of the Hindenburg Line that they were to attack had seen off many assaults earlier in the war, and was considered to be well fortified. In addition to the German fortifications, the terrain was cut by a series of ridges, which were for the most part solid. The problem was the depressions in between; these areas were marshy in nature. Additional hazards were the Forges Brook, and the closed terrain of the Bois de Forge, occupied by German troops. For Kurt this meant that he would have to traverse difficult terrain that featured obstructed lines of vision, complicating his ability to locate his objectives. Furthermore, in an era where much of a commander’s ability to control his troops depended on being seen, it limited Kurt’s ability to respond to his officers and NCOs. One way to counteract these problems was to keep closer together, but this ran the risk of higher casualties from artillery fire and automatic weapons.

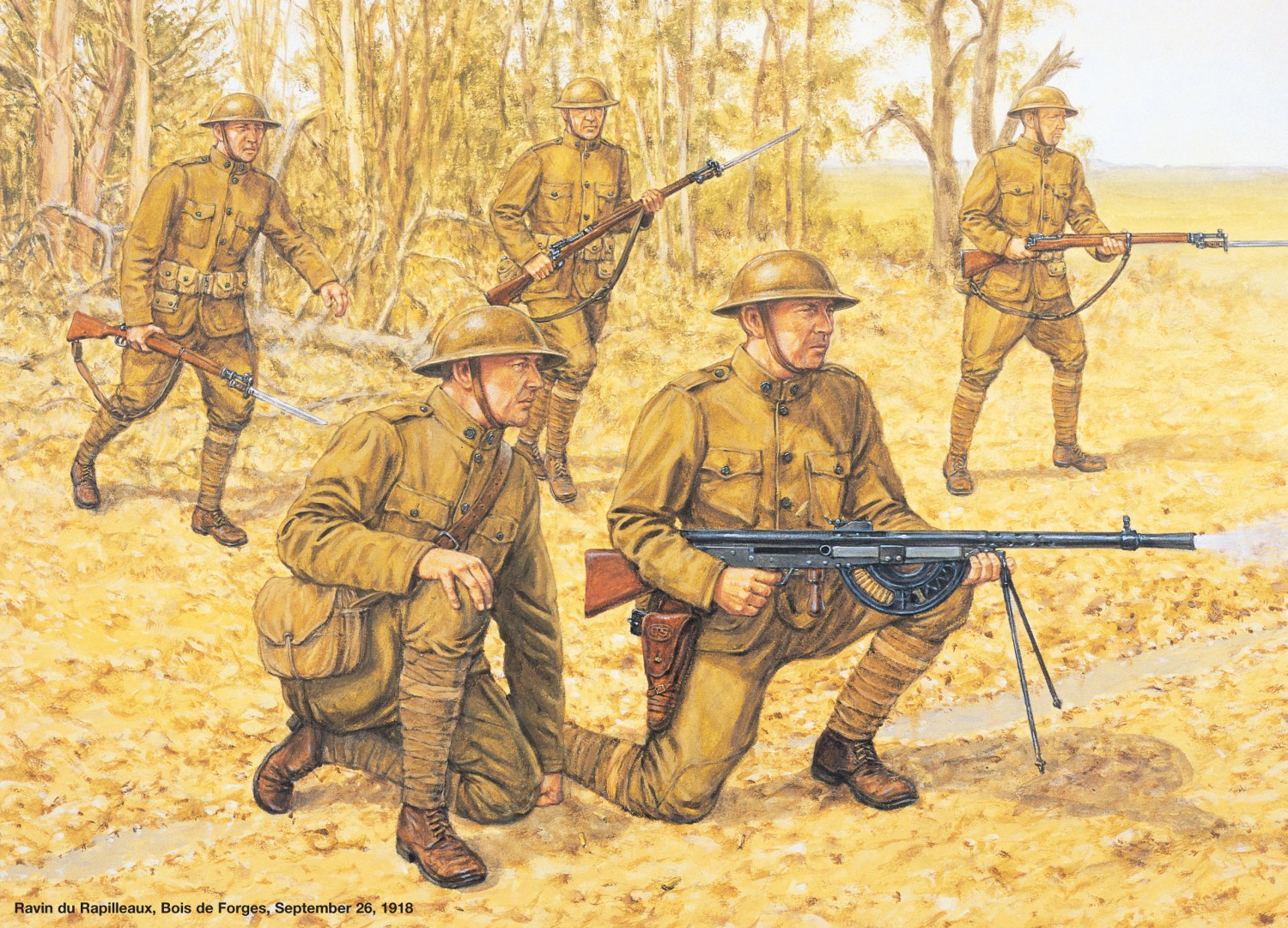

Illustration of an automatic rifle team at Bois de Forges

Taken from WAR 79: US Doughboy 1916-19

Under cover of the artillery bombardment, the 108th Engineer Battalion prepared approaches over the water obstacle to assist the attack. The assault that morning jumped off at 0530 hours, partially concealed by a heavy fog, and the 66th Brigade advanced toward the German positions. It took nearly an hour to cross the brook and re-form, and then, supported by a rolling barrage, the attack recommenced. The brigade, and in particular Kurt’s regiment, were in an important position for the entire battle plan. Being at the right of the US line north of the Meuse River, they were the door-hinge on which the American front was swinging. With this important task, the 132d could not afford to be delayed. Taking fire from the village of Forges itself, Kurt’s company was detailed to capture the town quickly. Fighting in a built-up area led to many of the same difficulties as fighting in woods.

The town itself was in a fairly destroyed state, as was common with most formerly inhabited places along the line. This gave the German defenders a certain advantage, as they had some cellars and the remains of other buildings to anchor their defense on. These localities could be connected with trenches to provide an integrated system. Furthermore, the ruins of the town could be used for concealment, and the broken nature of the area would disrupt any attackers. As had been shown in earlier fighting in towns such as Fleury near Verdun, these “strongholds” could become deathtraps. The time needed to reduce these positions could also be disruptive to the battle plans devised by the high command.

To take Forges, the company broke down into smaller groups, the platoons becoming reliant on their sections as fighting teams. In a like manner, the 132d’s sister regiment was setting about removing the threat of German machine-gun positions in the Bois de Forges. While the village could be defined as a built-up position, the training for “open warfare” was now to come into practice. To storm the German positions the Americans fell back on the principle of Fire + Maneuver = Offense. As defensive positions were identified the automatic-rifle and rifle-grenadier sections would lay down suppressive fire. This was designed to prevent the Germans from responding to the assault teams. Hopefully, the fire would force them to remain in shelter, and away from a firing position, or at least disrupt their ability to shoot accurately at the attacking squads. While this was taking place, the “bomber section” and the riflemen, with bayonets attached, would move to a position close to the defenders, and preferably sheltered from them. Once they were close enough, the bombers would throw grenades into the objective, and the riflemen would quickly follow up before any survivors could recover. If any of the defenders fled, the riflemen would be in a position to pick them off. Once the position was captured, the automatic riflemen and the rifle grenadiers would move forward and the cycle would begin anew.

Captain George H. Mallon won the Medal of Honor for his actions at Bois-de-Forges on 26 September 1918.

Often, if the objective were a village or other fortified area more advanced than the usual entrenchments, specialized assault engineers would accompany the troops. In American operations, these men were often French. Equipped with flame-throwers and explosive charges, they could help the infantrymen quickly overcome hardened defenses. French tanks often supported US troops until the American Army had developed a strong enough armor force. At Cantigny, in May 1918, both French engineers and Schneider tanks accompanied the 1st Division. Eventually the Americans developed their own armor corps to assist in these operations. While having some British heavy tanks, most of the American armor consisted of Renault FT-17s.

The defenders would, of course, try to make the attackers’ job as difficult as possible. Fighting positions would not be isolated, but rather be sited so as to support each other with interlocking fire. This put an additional burden on the US fire element, in that they would have to suppress several locations to protect the maneuver element. Depending on the terrain, the squads might be broken down further, so as to provide more direct support for the assault. Luckily for Kurt and his comrades, the attack on the 26th went swiftly and the town was cleared with a minimum of loss. Prisoners were taken, and the company had to hustle to catch up to the rest of the battalion and the main assault on the woods. The US troops kept up at a rapid pace, and within four hours the entire brigade had achieved the assigned objectives, with a penetration of four miles into the German positions. By the standards of World War I, this was a significant advance. Moreover, the casualties had been extremely light, again by the standards of the day. Only 36 men out of a total of 241 casualties were dead. The defenders had suffered heavily in comparison, relinquishing over 1,400 prisoners in addition to their casualties. Twenty-six artillery pieces and roughly 100 machine guns were captured as well. It was fortunate that the Germans were in a state of collapse. During an earlier attack at St. Mihel, one officer reported the Germans walking out with their hands up crying “kinder” to signify that they were older men with children at home in the hope of not being shot out of hand.

Osprey have a number of books focussed on the American contribution to World War One, such as Warrior 79: US Doughboy 1916-19, Men-at-Arms 386: The US Army of World War I and Men-at-Arms 327: US Marine Corps in World War I 1917-18.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment