On 16 October 1959 US General George Marshall died at the age of 79. To commemorate his death here is a look back at his life and some of the US troops that served in World War II.

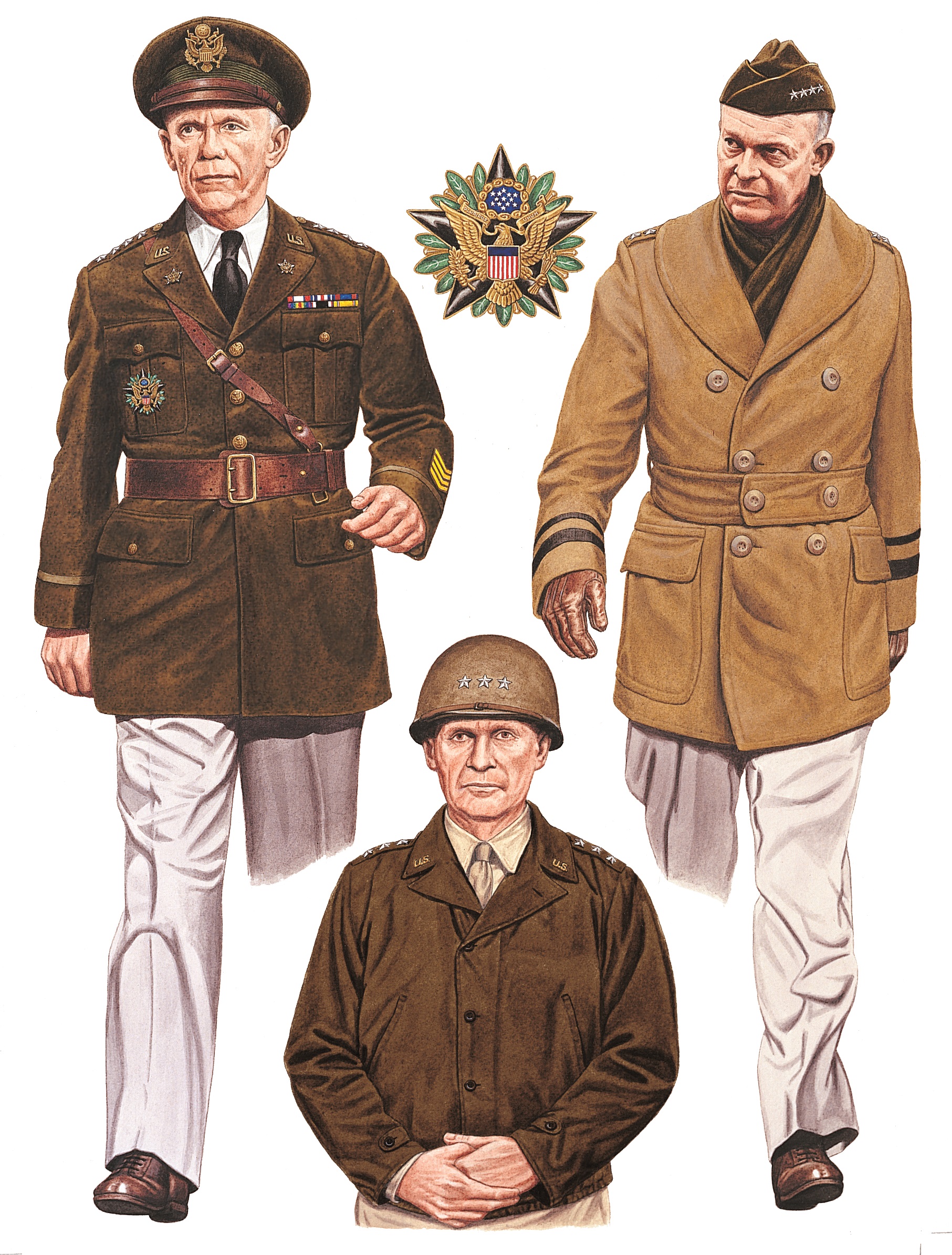

General G Marshall (left), General Lesley J. McNair (centre), General D. Eisenhower (right)

Artwork by Darko Pavlovic

General George Marshall

Extract taken from Elite 85: US Commanders of World War II (1) by James Arnold and Robert Hargis.

Marshall enjoyed President Roosevelt’s absolute confidence. Therefore, he had great influence at all of the major Allied wartime conferences. Although he possessed a fierce temper, he held it in check and adopted a practical approach to all problems. This, coupled with his lack of boastfulness, made for good relations with the British. Marshall hoped he would receive command of the Allied forces that would invade Europe. However, Roosevelt preferred him to remain in Washington, DC, where he would be available for close and frequent discussion. To his great credit, Marshall was able to prevent the president from meddling in military decision making. Marshall made another great contribution to the American war effort by his selection and assignment of senior officers. In addition, he made sure that generals who needed specific technical assistance received appropriate staff officers. Marshall shares with Admiral King the responsibility for failing to unify command in the Pacific. Pacific operations unwisely remained divided between the navy under Admiral Nimitz and the army under General MacArthur. The resultant two-prong advance against Japan gave the Japanese the opportunity to concentrate forces to defeat the widely separated American efforts. Fortunately, the Japanese failed to seize the chance. Because of Marshall’s ability to provide grand strategic direction and to coordinate strategy with the Allies, Winston Churchill, who liked and admired him, bestowed upon him the honorific, “the organizer of victory.”

Marshall resigned from active service on November 20, 1945. President Truman quickly persuaded him to return to public service. After Marshall had held several diplomatic roles, in January 1947 Truman appointed him as Secretary of State. Marshall held this position until 1949, during which time he supervised the postwar reconstruction of western Europe, the famous Marshall Plan. Unjust attacks by the anti-communist zealot, Senator Joseph McCarthy, helped drive Marshall from public service in 1951. Two years later, Marshall became the first soldier to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. He died in 1959.

Bastogne, December 1944

Extract taken from Men-at-Arms 350: The US Army in World War II (3) by Mark Henry.

(1): Rifleman, 28th Infantry Division.

The 28th Division was originally a National Guard outfit from Pennsylvania, the ‘Keystone State’. Its red keystone patch was nicknamed by the 28th’s GIs the ‘Bloody Bucket’ after its losses in Normandy and – with the 4th and 8th Divisions – in the meatgrinder of the Hürtgen Forest; the 28th was then sent to the ‘quiet’ Ardennes sector to rest... Its two-day stand in the face of the advancing 5.Panzer-Armee gave the 101st Airborne time to occupy Bastogne. This soldier, wearing a ‘home-ripped’ snow camouflage cape and helmet cover made from a bedsheet, is probably from the Quartermaster company or some other divisional support unit, pitched into the fighting at short notice. Under his sheet he wears a first-pattern mackinaw with wool-faced shawl collar, a five-button sweater, the usual drab wool trousers, a pair of the new M1943 ‘buckle boots’, and wool trigger-finger gloves. His equipment is minimal: a rifle belt, and a musette to carry all his other gear.

(2): Bazooka gunner, 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.

The standard issue enlisted men’s wool melton overcoat was much used by the Airborne during the Battle of the Bulge. (One paratrooper of the 82nd is reputed to have said to a worried tank crew, ‘Looking for a safe place? Well, buddy, just pull in behind me.’) Under his coat this ‘glider-rider’ wears the standard M1943 combat jacket and buckle boots now becoming common throughout the ETO. His baggy trousers with cargo pockets are the only remaining sure sign of his Airborne status, though his belt equipment includes one of the limited-issue ‘rigger’s’ ammunition pouches peculiar to the Airborne. He is armed with the M1 carbine, and a M3 trench knife strapped to his boot; some photos show civilian knives carried as well. His main weapon, however, is the latest M9 folding version of the 2.36in anti-tank rocket launcher or ‘bazooka’. A white ‘club’ helmet symbol identifies his regiment. (Inset) By 1945 the ‘glider-riders’ finally received this ‘wings’ badge and the same hazardous duty pay as their parachute brethren. The bronze stars mark two combat landings, in Normandy and Holland.

(3): T/5, 20th Armored Infantry Regiment, 10th Armored Division.

Active in the capture of Metz in November 1944, the 10th Armored Division had its Combat Command B inside Bastogne throughout the siege. This GI wears the new four-pocket, sateen-shell M1943 field jacket, introduced as a universal garment for all branches of service; he has not yet received the matching trousers, but is fortunate in having secured himself a pair of M1944 shoepacs. He is armed with the M1 Garand, and grenades including a smooth-cased Mk III concussion type. Among his belt equipment is the folding-head entrenching tool based on a German design, with a cut-down haft. His web equipment is in the new greener OD shade 7 now reaching the front in quantity, although existing stocks of items in the sandier shade 9 would continue to be issued for years. Since it is of little practical use this GI has dispensed with his bayonet. More useful is the blanket just visible tucked through the back of his belt. He is carrying the baseplate for an 81mm mortar. Along with the 101st Airborne and 10th Armored the Bastogne garrison included elements of the 9th Armored and 28th Infantry divisions, the 705th Tank Destroyer Bn, 1128th Engineer Combat Group, and five corps-level artillery battalions.

Morocco & Algeria, November/December 1942

Extract taken from Men-at-Arms 347: The US Army in World War II (2) by Mark Henry.

(1): Lieutenant-colonel, Ordnance, 2nd Armored Division.

This ‘short’ colonel (addressed out of courtesy as ‘Colonel’) wears the standard khaki summer shirtsleeve uniform with officer’s belt buckle. (Medal ribbons were also authorised to be worn with this shirt, though this officer chooses not to.) The brass flaming bomb insignia on his left collar point identifies him as serving in the Ordnance branch, responsible for weapons, ammunition, and the repair and maintenance of vehicles and hundreds of other GI items; in the 2nd Armored this element was provided by the former 17th Ordnance and 14th QM Bns combined into a single divisional Maintenance Battalion. Rank is shown by the silver leaf on his right collar and cap. This headgear is the khaki overseas cap, piped with mixed gold and black for officers, but he could also wear the khaki version of the leather-visored service dress hat. The patch of the Armored Force, with the divisional number, is worn on the left shoulder. After briefly fighting the Vichy French, in November 1942–January 1943 the 2nd Armored, garrisoned in Morocco, provided G and H Companies, 67th Armored Regt, to the British 78th Division fighting in Tunisia. The ‘Hell on Wheels’ division – whose main units were the 66th and 67th Armor, 41st Infantry, 82nd Recon Bn, 14th and 92nd Armored Field and 78th Field Artillery – would see its first major combat in Sicily, where it landed at Gela with the 1st Infantry Division on 10 July 1943.

(2): Infantry private, BAR gunner, 9th Infantry Division.

Because of the bad blood between the British and the Vichy French caused by events earlier in the war, the Allied high command – who wanted the French garrison to recognise the Allied invaders as essentially friendly – ensured that US troops generally led the landings, and came ashore wearing white armbands and US flag shoulder patches or brassards. This infantry squad Browning Automatic Rifle gunner wears the standard first pattern herringbone twill (HBT) uniform, identified by its two-button waistband, buttoned cuffs and pocket details; later HBTs would have large breast pockets and thigh cargo pockets. Note the haversack for the M1A2 or M2A1 gasmask, marked with the symbol of the Chemical Warfare Service; and the BAR magazine belt with six large pockets. Veteran BAR gunners commonly dispensed with the M1918A2 weapon’s extraneous features such as the bipod, to reduce its weight from 18 to 15lbs. This young soldier’s eye glasses are the standard Army metal frame issue. He wears his helmet chinstrap buckled in the regulation manner; veterans soon violated this requirement for fear of literally losing their heads in the concussion of a shell burst.

(3): Sergeant, Military Police, II Corps.

Each division had an MP company, and independent MP units were also assigned as corps and army assets. As enforcers of discipline and regulations, rear-area MPs inevitably had a reputation for officiousness and short tempers, and had few admirers among the GIs. This sergeant sports the standard white helmet markings and white-on-black armband used throughout the war. His khaki ‘chino’ service uniform was commonly worn in rear areas in the Mediterranean theatre; as part of a II Corps HQ guard detail he is neatly turned out, complete with necktie; and note the whistle and chain. Below the II Corps left sleeve patch his rank chevrons are machine-woven in dull silver on black. He is armed with the newly produced M1903A3 rifle, closely based on the World War I Springfield 03; and carries the early war M1905 long bayonet in the new OD plastic scabbard.

The Philippines, 1942

Extract taken from Men-at-Arms 342: The US Army in World War II (1) by Mark Henry.

(1): Corporal, US Infantry, Philippines Division.

This corporal is among the 23,000 US and Filipino regular troops defending the Philippines against the Japanese onslaught. His khaki cotton Class C (‘chino’) uniform is comfortable, but its light colour and lack of durability will be found wanting in combat; his rank chevrons are displayed on both sleeves. His helmet is the M1917A1 ‘dishpan’ with the newer khaki chinstrap. Although a small number of M1 Garands were available in the Philippines, this soldier, like most, is armed with the standard M1903 Springfield bolt action rifle. Forsaken by the US, the ‘Battling Bastards of Bataan’ said that they had ‘No Mama, no Papa, and no Uncle Sam’.

(2): 1st Lieutenant, US Cavalry.

Officers’ khaki shirts differed from the EMs’ in having epaulettes (shoulder straps), and in the Philippines the pocket flaps were often customised as shown. This officer wears his rank bars at the end of his epaulettes and cut-out national and branch insignia on the collar points, as required in prewar regulations. This configuration was soon changed to wearing rank on the right shirt collar and branch on the left. This cavalryman has been assigned to an infantry unit and so wears the appropriate boots and leggings. His M1936 pistol belt and supenders support his .45cal semi-automatic pistol in a russet holster, web double-magazine pouch, World War I first aid pouch and (obscured here) canteen. His Thompson SMG is the prewar M1928 model with the distinctive top bolt and 50-round drum magazine.

(3): Filipino rifleman.

Gen MacArthur was in the process of building up the new 100,000-man Filipino Army for the impending war with Japan which was anticipated to begin no sooner than mid-1942. Unprepared for war in late 1941, they performed poorly at first, but by the time the combined US/Filipino regulars were defending Bataan they had become viable soldiers. Filipino units were led by both Filipino and US officers. This well equipped man is armed with the World War I surplus M1917 (P17) rifle and helmet. If he survives the fighting to be captured he will probably have to endure the ‘Bataan Death March’ – during which more than 600 US and 5,000 Filipino soldiers would die of neglect, exhaustion and brutality. He will suffer unimaginable hardship as a prisoner in Japanese hands until liberation in 1945.

If you are interested in reading more, here is a selection of Osprey's books on the United States of America in World War II:

For General G. Marshall:

Elite 85: US Commanders of World War II (1)

For US Forces in World War II

General Military: American Knights

Duel 69: US Navy Carrier Aircraft vs IJN Yamato Class Battleships

Campaign 284: Guadalcanal 1942–43

General Military: Airborne: The Combat Story of Ed Shames of Easy Company

Elite 203: World War II US Navy Special Warfare Units

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment