Tuesday 15 December marked the 125th anniversary of the death of legendary Native American Chief Sitting Bull, and so we felt it would be fitting to end the week with a look at the history of some of North America's native people.

Warriors, 1760s-1790s

Extract taken from Men-at-Arms 467: North American Indian Tribes of the Great Lakes by Michael G. Johnson

Illustration by Jonathan Smith

1: Shawnee warrior, c.1774.

The Shawnee lost their Kentucky hunting grounds after the 1768 Ft Stanwix treaty, but their scattered groups gathered in the Ohio country and vigorously resisted white encroachments from Virginia. Based on a sketch from life, this warrior wears a woollen trade blanket, possibly English; black buckskin leggings with quillwork decoration; and moccasins with ankle collars, typical of the Woodland tribes. His silver ear decorations might be either traded, or produced by Indian smiths. Note the saber-shaped wooden war club.

2: Kaskaskia warrior, 1796.

This leading sub-tribe of the Illinois confederacy suffered continuous wars with the Wisconsin tribes and the Iroquois, and lost great numbers from European-introduced diseases. Few were left by 1800, but a sketch from life in c.1796 shows a warrior with roached hair, ostrich feathers, a black-and-white headband with silver ornaments, silver ear-spools and armbands, a quilled knifecase, and an iron tomahawk. The last of the Kaskaskia joined the “Peoria” – remnants of several Illinois and Miami groups – and ultimately found a home in Oklahoma.

3: Great Lakes warrior, Pontiac War, 1763.

This warrior, from the coalition of Great Lakes tribes that rose against the British, wears a French military-style hat and coat. His green trade-cloth leggings are based on museum examples, showing the earliest appearance of ribbon appliqué work during the second half of the century – probably an influence from Indians further east and north. Note the quilled pouch, the belt, and the triangular porcupine-quilled knifecase at his neck.

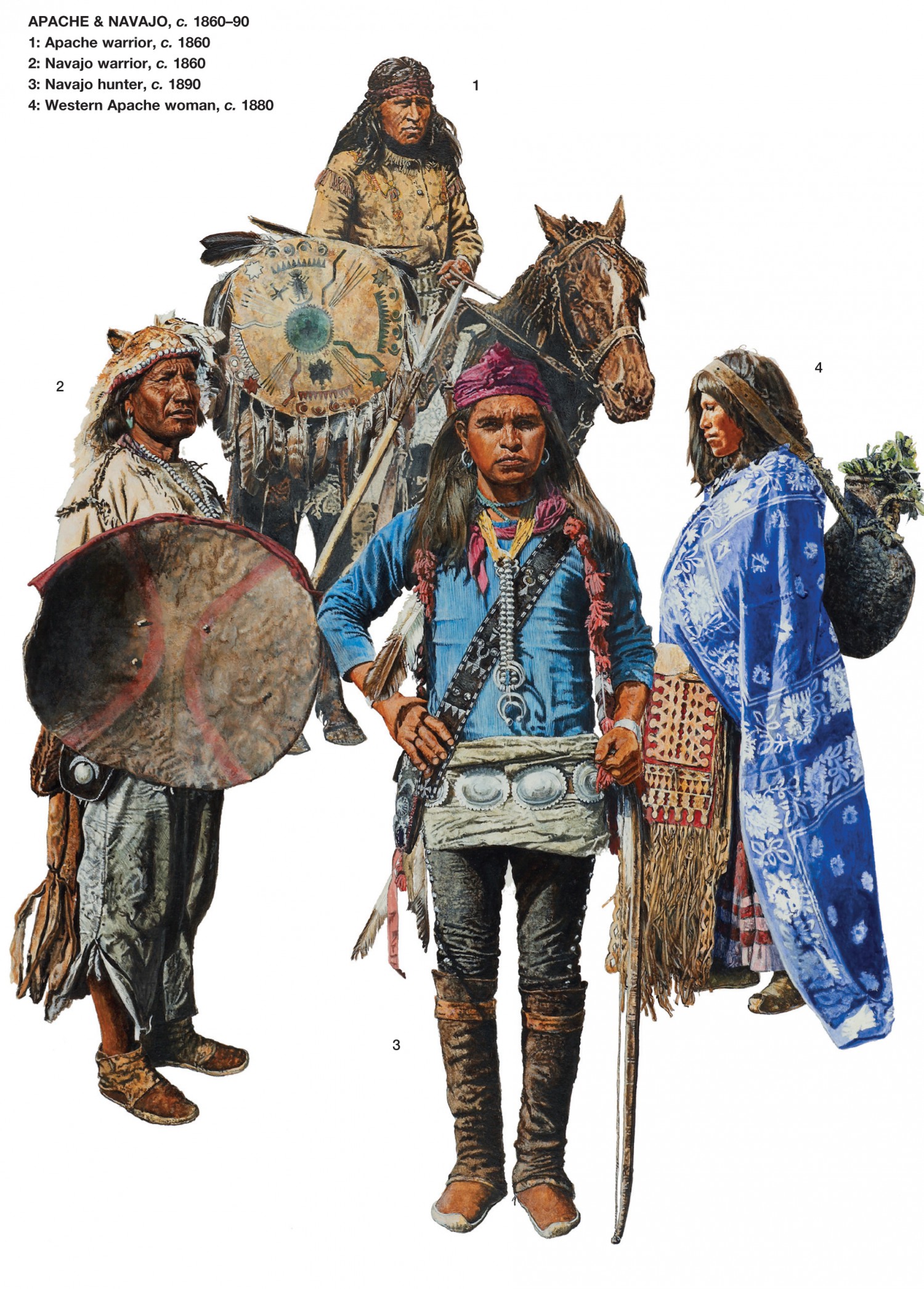

Apache and Navajo c. 1860-90

Extract taken from Men-at-Arms 488: American Indian Tribes of the Southwest by Michael G. Johnson

Illustrated by Jonathan Smith

1: Apache warrior, c. 1860.

This mounted warrior wears a buckskin jacket patterned after US military clothing but painted with traditional Apache symbols of power, as is his shield. Full-scale Apache hostilities with the Spanish ended in 1786 when the latter began attempting a pacification policy, but when this policy collapsed after Mexican independence in the 1820s the Apache resumed intensive raiding into Sonora. After 1853 hostilities with Anglo-Americans increased, continuing intermittently until Geronimo’s surrender in 1886.

2: Navajo warrior, c. 1860.

Close relatives of the Apache, the Navajo probably followed them into presentday northern New Mexico and Arizona, but they were to be more influenced by Pueblo culture, learning to weave textiles for clothing and acquiring some agriculture. They often joined Apache bands to raid Mexican and later American settlers, particularly during the Civil War, when US military posts were thinly manned. This warrior wears a cap made from a mountain lion’s skin, including the ears, to invoke the animal’s hunting skills. His shirt and trousers are of Mexican type, and his moccasin boots are of a type with the uppers attached to a large, hard sole above the foot imprint. Note his substantial combat-shield and metal-headed spear.

3: Navajo hunter, c. 1890.

About the time of their internment at Bosque Redondo in 1864–68 the Navajo learned the art of silver-smithing from Mexicans, and by the 1890s men and women were wearing “squash-blossom” necklaces and concha belts made from coin-silver. The hunter holds a bow, and wears high moccasin boots; his bandolier is made from commercial leather.

4: Western Apache woman, c. 1880.

She is holding a double saddlebag of buckskin decorated with cut-outs and red cloth. From a tumpline round her head she carries a tus – a basket caulked with piñon gum to carry water. The Western Apache were expert basket-makers, typically using thin strips of fiber, willow, leaves or grass wrapped around three rods and coiled into a continuous spiral. There were two distinct types: plaques, shallow dishes and ollas (storage baskets), and twined burden baskets and water-carriers.

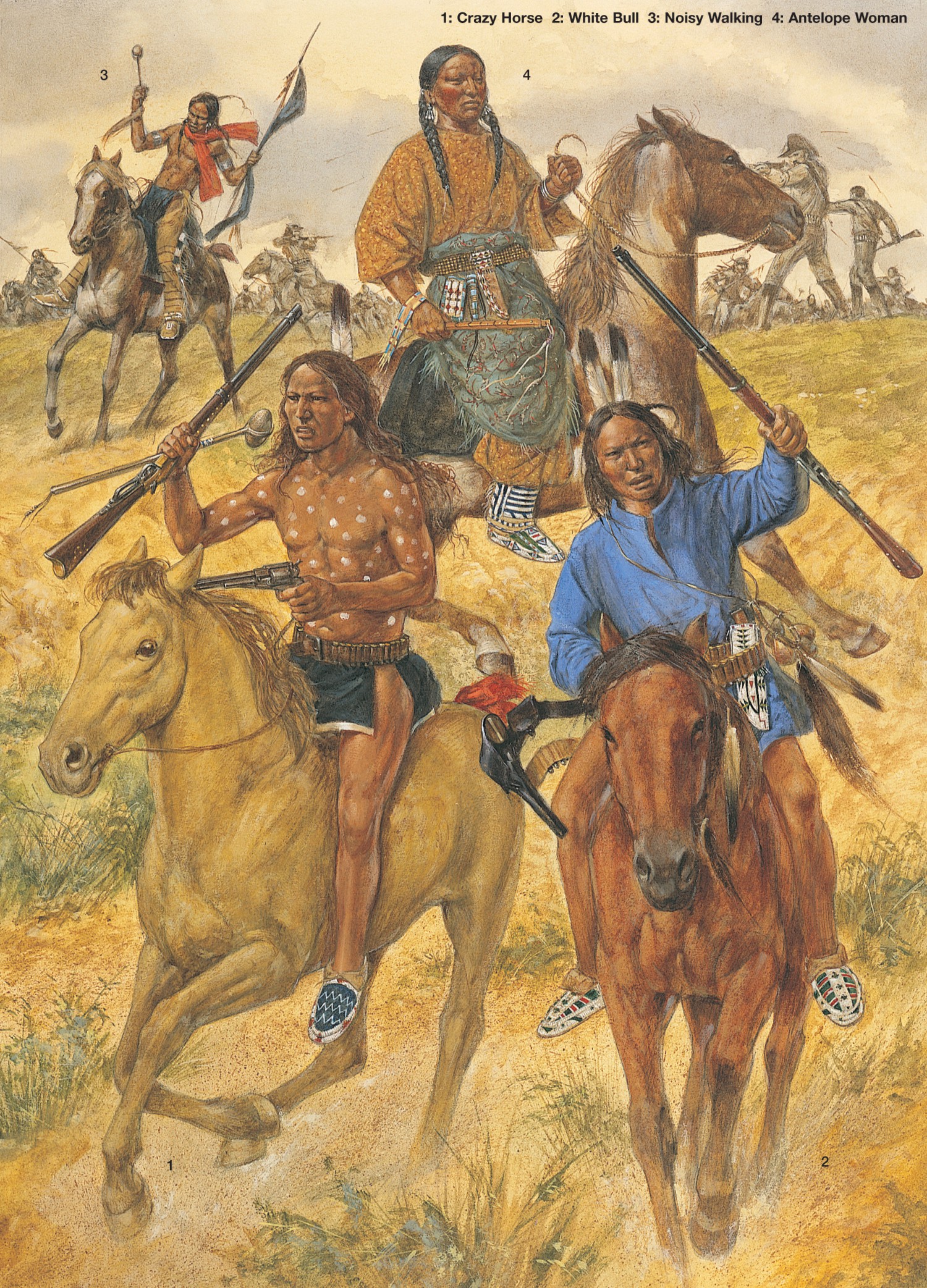

Crazy Horse, White Bull, Noisy Walking and Antelope Woman at the Battle of Little Bighorn

Extract from Men-at-Arms 408: Warriors at the Little Bighorn 1876 by Richard Hook

Illustration by Richard Hook

1: Despite the amount of information available on Crazy Horse he remains a man of mystery, and his appearance at the Little Bighorn still cannot be described with any certainty. The ledger drawings of Amos Bad Heart Bull provide the main reference for this figure; the drawings were approved and even directed by that artist’s uncles and father, all Little Bighorn veterans. Amos Bad Heart Bull’s drawings show Crazy Horse wearing a single eagle feather upright in his unbraided hair, which is described by Short Bull and Little Killer as unusually brown and wavy. Selvedge-edged trade cloth belted at his waist could be interpreted either as a small blanket, or more likely – as shown here – the ends of his breech clout pulled up and tucked under his cartridge belt. It is confusing that the pictographs all show Crazy Horse’s body painted with red spots on yellow, contrary to all descriptions that he painted himself with white spots representing hail, as portrayed here. Did Amos’s informants tell him that, contrary to other information, Crazy Horse’s paint was different on this day from that which he normally wore? – or, not having the luxury of opaque white paint available, did the artist take license by using colors other than described? The drawings do not show the calfskin cape often described. From this it might be concluded that it was worn at the Rosebud battle but not at the Little Bighorn. All the Amos Bad Heart Bull drawings show fully beaded moccasins, a stone-headed club, a rifle (shown here as a brass-tacked ‘Yellow Boy’ Winchester) and a pistol (shown here as a .44 Remington percussion revolver).

2: The main sources for this figure are White Bull’s pictographs showing himself at the Little Bighorn, and his own descriptions. His hair is unbraided, decorated with two upright eagle feathers. He wears a cloth shirt gathered by two cartridge belts, through which his beaded knife sheath is thrust. He wears no leggings; White Bull made a point in interviews of mentioning that he removed them between the Reno fight and Deep Ravine. A thong over his right shoulder supports his personal war medicine: hung from a rawhide loop are four buckskin pouches, a buffalo tail and an eagle feather. He carries a Winchester carbine and a captured holstered pistol and cartridge belt. White Bull’s horse has a scalp hanging from the rope bridle, and an eagle feather in its mane. It is of interest that White Bull drew himself after the battle, driving off captured horses with his horse now festooned with eagle feathers – probably ‘heraldry’ of his recent achievements.

3: Noisy Walking is shown wearing a cloth breech clout, Cheyenne buckskin leggings with beaded strips, and partially beaded moccasins. He is armed with a lance decorated with trade cloth and a stone-headed club. As described by Antelope Woman, a red cloth is tied around his neck so that he may be recognized by his aunt during the battle.

4: Antelope Woman is shown wearing typical women’s dress of this period. Over a patterned cloth dress is a shawl, gathered at the waist with a brass-tacked harness-leather belt, from which hang an awl case, a strike-a-light case and her knife sheath, all decorated with beadwork of typical Cheyenne designs. Her cheeks and hair parting are painted red. Her jewelry consists of German silver earrings and bracelets. Note that she wears beaded hard-soled moccasins and beaded leggings. She holds a wooden quirt with a beaded wrist strap.

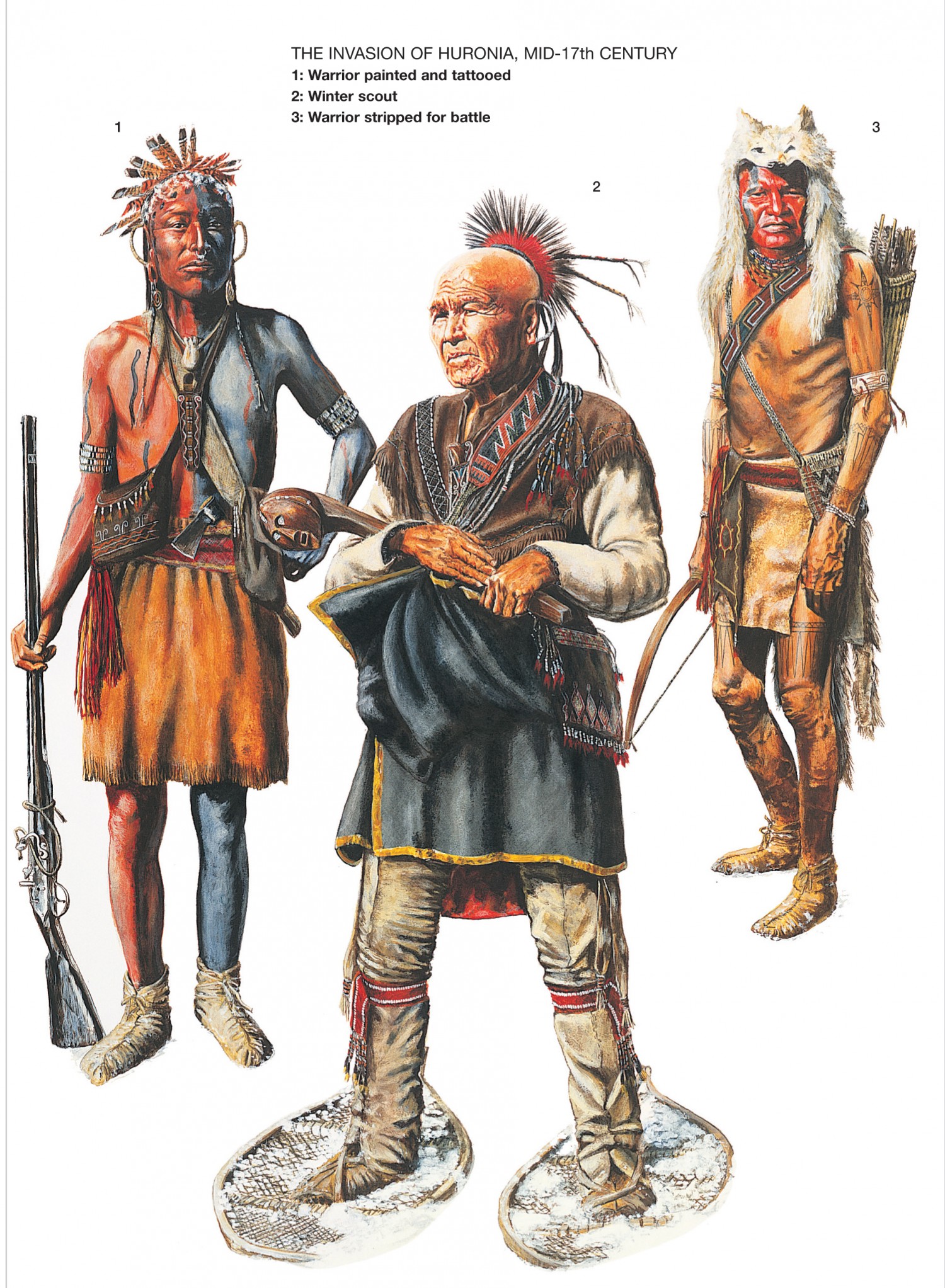

The Invasion of Huronia, mid-17th Century

Extract from Men-at-Arms 395: Tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy by Michael Johnson

Illustration by Jonathan Smith

1: Warrior painted and tattooed, armed with a matchlock musket.

2: Winter scout, wearing snowshoes.

3: Warrior stripped for battle, with bow and arrows.

Every young Iroquois male was expected to be a warrior, and war captains tested their bravery. The departure of a war party was usually preceded by feasting and dancing on a “dance ground” around a red-painted post, which the warriors struck with their weapons. Iroquois did not usually wage war in wintertime when the leaves were off the trees and it was difficult to find cover. Before iron arrowheads, metal tomahawks and guns arrived in Indian hands, warriors used a kind of body armor made from wooden strips laced together, and extra protection was provided by huge shields. The principal weapons were the bow and the war club. Warriors on the trail carried a bag of roasted cornmeal. Iroquois braves were heavily tattooed and many painted their faces half-red and half-black. Scalps were taken from the fallen; and prisoners were brought back to the villages. These captives were sometimes adopted by females, thus replacing the casualties of warfare; but more often they were tortured for several days, burned alive, scalped, beheaded and disembowelled. Such was the traditional nature of the wars that intermittently raged between the Iroquois and the four tribes that formed the Huron confederacy. The French control of the fur trade throughout the Great Lakes via Huron middlemen, and the depletion of their own hunting grounds, was the prime reason for the Iroquois invasion of Huron territory in the spring of 1649. Jesuit priests who had already established missions amongst the Hurons wrote yearly reports to their Paris headquarters (published as The Relations); these recorded Huron culture, and the series of defeats due to which the Jesuits position became untenable. Many Hurons perished at the hands of the Iroquois; some took refuge amongst neighboring tribes; some were adopted by the Iroquois, particularly by the Seneca; some accompanied their French missionaries to Quebec; and the remainder joined the Petun (now called Tionontati) and moved to the Detroit and Ohio country, where they became known as Wyandot (Wendat).

Warrior Societies

Extract taken from Men-at-Arms 344: Tribes of the Sioux Nation by Michael Johnson

Illustration by Jonathan Smith

1: Omaha Society, c1890.

Amongst the Missouri River tribes such as the Omaha, Ponca and Pawnee, warrior societies wore distinctive attire usually consisting of a porcupine and deer hair roach (headdress), a bustle or ‘Crow Belt’, and a circle and trailer of the feathers of birds of prey – whose scavenging of the field after battle provided the symbolic connection with warfare. From the top of the bustle two feathers projected, representing slain warriors – one a friend, the other an enemy. The belt which secured the bustle behind the waist also held braids of plaited sweetgrass – hence the popular name of the characteristic dancing style, the ‘Grass Dance’. During the 1860s these ceremonies were adopted from the Omaha tribe by the Western Sioux, who named it the Omaha Dance or Society. In the late 19th century its function became largely social and it was popular during Fourth of July celebrations. It has formed the basis for the continuing male powwow dancing up to modern times. In early reservation days dancers sometimes used long whistles, the open end carved to represent a bird’s head. The Crow Owners Society members wore similar bustles of feathers from birds of prey.

2: Miwatani or Mandan Society, c1870.

An important military society of the Teton Sioux, this is said to have originated long ago with a man who dreamed of an owl, in consequence of which its members used only owl feathers to fletch their arrows. At meetings each member carried a rattle made of the dew claws of deer fastened to a beaded stick, as used in many Sioux dances. Warrior society sashes were sometimes pinned to the ground in battle so that there would be no retreat. Quirts notched and carved in a zig-zag pattern to represent lightning bolts were used by officers of several military societies.

3: Strong Heart Society, c1880.

The Strong (or Brave) Heart Society was probably founded by Sitting Bull (our model here), Gall and Crow King. They wore headdresses consisting of buckskin skullcaps covered with fringes of ermine skin, split curved buffalo horns and owl feathers. Some members carried ring-shaped rawhide rattles, and lances decorated with a row of eagle feathers attached to a strip of red trade cloth extending the whole length of the shaft. In their dances they adopted a bobbing, up-and-down movement. Strong Heart Society shields were usually painted with an eagle design and trimmed with eagle feathers.

If you'd like to read more take a look at Men-at-Arms 467: North American Indian Tribes of the Great Lakes, Men-at-Arms 488: American Indian Tribes of the Southwest, Men-at-Arms 408: Warriors at the Little Bighorn 1876, Men-at-Arms 395: Tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy and Men-at-Arms 344: Tribes of the Sioux Nation.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment