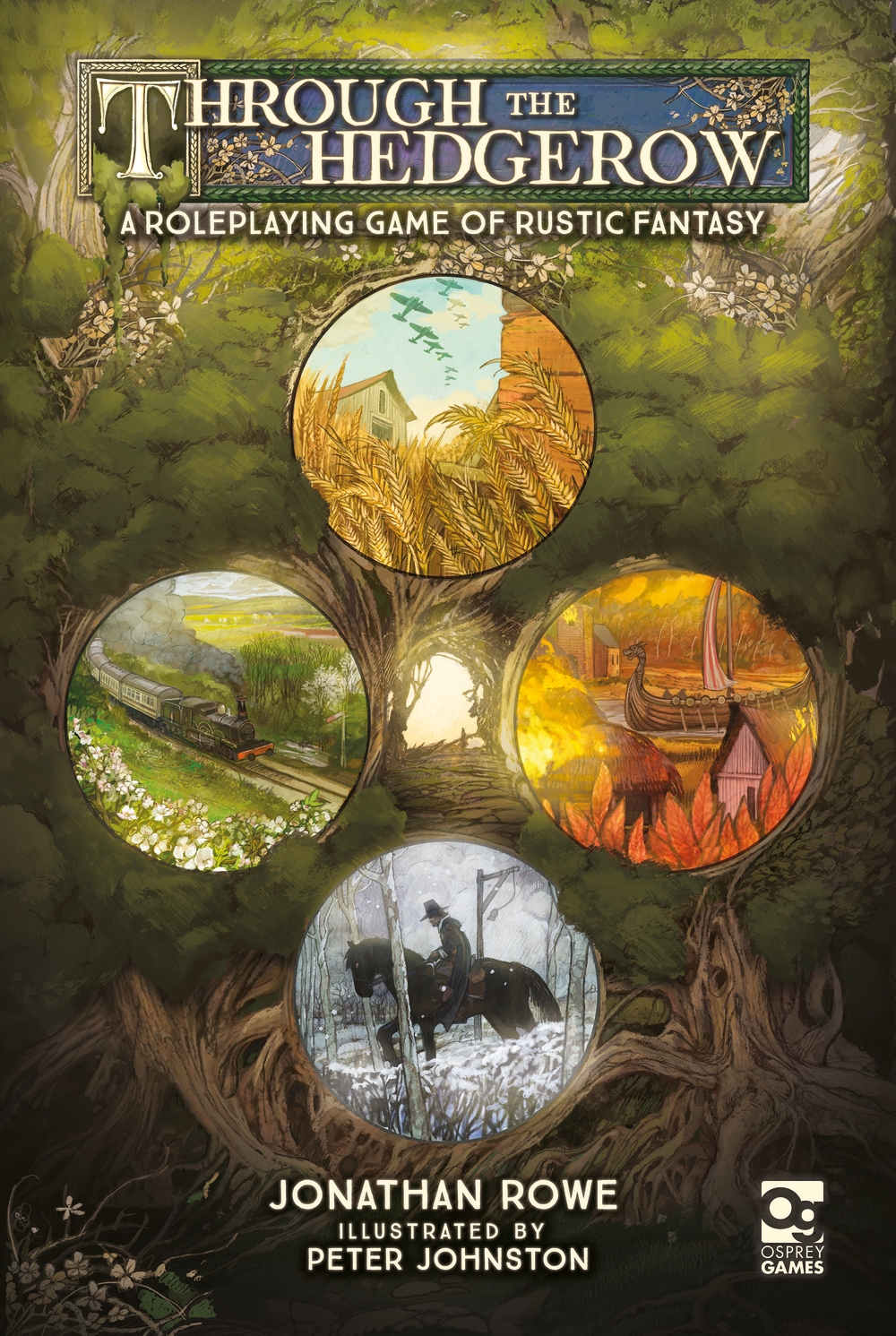

For our last blog on next week's rustic fantasy RPG Through The Hedgerow, the author covers the Light that you'll be serving, the Dark that you'll be facing - and the Doom that will await you whether you succeed or fail...

Behind the facade of normalcy, two forces contend. The farmer ploughs his field, sows the fertile seed. Orders his land with neat hedgerows, tends fruit in the orchards, and blesses his family as they sit together at supper. This is the world of the Light. But at night, the Dark arises. The wolf scratches at the locked gates. The earth yawns open and disgorges the bones of the hungry dead that roam the lanes and lurk by stiles, waiting for the unwary shepherd hastening home late, far too late, as the sun slips from the hilltops and the night stifles his scream.

Through the Hedgerow borrows this trope from classic fantasy – but notably from Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising series (quite simply the best Young Adult fantasy series, published in the 1970s and investing the British countryside with apocalyptic significance – it’s been a huge influence on me) and perhaps F. Paul Wilson’s Adversary Cycle is rattling around in there too. With my professor hat on, I can tell you that it’s a mythological concept rooted in ancient Zoroastrianism and termed ‘dualism’ by scholars. It’s the idea that the world around us is an arena in which two cosmic forces contend: the Light and the Dark.

The Light is the force that nurtures: it is creativity, discovery, lawful and ordered living, perhaps life itself. The Dark is its opposite: destruction, ignorance, chaos, death.

In Through the Hedgerow, the player characters have been plucked from their ordinary lives – or, in the case of Fay characters, their already-extraordinary lives – to serve the Light. They might not have chosen this service. They might resent it. It will certainly cost them dearly: at the very least, it will cost them their innocence.

The Light and Your Doom

Serving the Light means labouring under a Doom, which is a tragic (or at least bittersweet) fated end. You learn your Doom when you create your character. Perhaps you are fated to betray your companions, turn to the Dark, die defending someone you love, or settle down and lose all memory of the Light and the Dark and your erstwhile comrades.

Each character has a Doom Die which starts small (d4) but gets bigger as your Doom draws nearer. That’s not a bad thing though – you can roll your Doom Die for any Check or Challenge, so the bigger it gets, the more powerful your character is. Advancing the size of your Doom Die is like ‘levelling up’ in conventional RPGs, except for the fact that you can retreat the size of your Doom Die later, which is ‘levelling down’. Why would you want to do that? Well, read on.

Your ultimate Doom also determines your Doom Trigger: a set of circumstances that reveals your heroic qualities, but also your destructive flaw. If it is your Doom to betray your cause, then your Doom Trigger occurs when you get up to something important behind your comrades’ backs or against their wishes. A Doom Trigger only happens once per adventure, if it happens at all, but it causes your Doom Die to advance in size, so that d4 becomes a d6. It also makes your Doom Die ‘unlimited’ which means you can use it over and over and really rely on it.

Relying on your Doom Die is a risky course of action, however. If you roll the highest possible number on your Doom Die, that also makes it advance in size. This also can occur once per adventure. This means even a starting character could trigger their Doom then roll the highest number when using their Doom Die and end up with a d8 Doom Die, which is quite a powerful asset. The Doom Die can also increase when you gain rewards at the end of an adventure. In fact, there’s one reward that forces you to advance your Doom Die whether you want to or not. The starting character I imagined earlier could end their first adventure with a d10 Doom Die.

Isn’t that a good thing? Well, yes, insofar as it makes you powerful. Being able to throw a d10 at any particular Check or Challenge is a significant benefit. The problem is, sooner or later your Doom Die will advance past d12 size. When that happens, your character’s Doom is at hand: you are about to lose your character.

Your Doom is at Hand

Characters in Through the Hedgerow aren’t at risk of dying on a routine basis. Even if they are defeated by a Challenge, they are usually just distracted or weakened or possibly captured. It’s a rare Challenge that threatens to vanquish them, removing them from the adventure. Even vanquished characters can return in a future adventure: if the Judge allows it, the Light snatches its servants away from peril.

There’s no getting round your Doom, however. Once that Doom Die peaks, your character’s story has come to an end.

Through the Hedgerow imagines this Doom to be a collaborative process between the player and the Judge. The Doom should come about in a way that fits the theme of the adventure and respects the arc the character has been travelling. It might be brutal and tragic, or whimsical and bittersweet. Were you stabbed in the back by someone you trusted – or did you fall in love with the Elf Maiden of the Old Moor and decide to stay with her, renouncing your life of adventure? The Doom doesn’t have to occur immediately and it might take place in the next adventure you take part in, which would allow the Judge to work your character’s departure into the story in a dramatically satisfying way. But go you must!

But What IS the Light?

It’s easy to represent the Light as a force of cosmic goodness and the Dark as diabolic evil. Even handled this way, there’s room for a lot of depth in character development. Some Briar Knight characters will be idealistic in their service of the Light, but many are bitter or reluctant.

Hodkins are human champions who served the Light in their own age and were gifted – or cursed – with immortality to continue their service across the centuries. They have lost their homes, families, loved ones, everything they knew, to become warriors in an unending war across time. For many of them, their eventual Doom is a blessed release, “a consummation devoutly to be wished”, as Hamlet says.

Buggebers are Fay monsters created to be minions of the Dark. Some have repented and seek atonement by serving the Light, some have offended their former Lords and the Light offers them protection, others are prisoners whose service to the Light is grudging at best.

For the bird-faced Ouzels, serving the Light is a political manoeuvre in the Courts of Fayrie: some see themselves as knights and strategists in a grand campaign, but others seek personal reputation or the means to defeat ancient rivals in the struggle between their Houses.

Dualism gets a lot more interesting as a fantasy trope when the Light and the Dark don't perfectly align with ‘Good’ and ‘Evil’.

The Light promotes or perhaps arises from human flourishing – but in a rather abstract way. The Light tends to focus on the achievements of certain ‘great souls’ throughout history, strives to protect extraordinary treasures or locations of beauty, or tweaks the destiny of pivotal figures. It isn’t concerned with the ‘greater good’ and is unconcerned with causing suffering to bystanders as it furthers its plans. Briar Knights might be sent to abduct a child from its parents and entrust it to new guardians so that the child will grow up according to an important destiny – but along the way a family has been divided and parents left bereft.

Stories in Through the Hedgerow will often feature these dilemmas and part of the fun of roleplaying Briar Knights comes from exploring their reactions – from both mortal and immortal perspectives – to making these fraught decisions. Eventually characters will exhaust their idealism (if they started with any) and this is where the Doom comes in: there isn’t only a game mechanism bringing your character’s career to a close because Briar Knights end up seeking their Doom. Eventually, Briar Knights end up rebelling, or walking away, or finding their own corner of a friendly field to die in.

What About the Dark?

If the Light isn’t entirely ‘good’ then what about the Dark? Is it evil?

In many ways, yes. The Dark employs monsters and undead that hate humanity or else regard mortals as chattel or dinner. But it’s worth distinguishing between ends and means. Among the agents of the Dark are more philosophical villains, such as the inquisitors of the Witch Harrow and the emissaries of the Raven Margrave. These adversaries claim to have seen a vision of the future so dreadful that any means are justified in averting it, including holding back human progress, extinguishing inspirational leaders and art, and unleashing plagues and disasters. Even an impoverished or oppressed humanity is preferable to what the future holds in store. Viewed this way, the Dark offers a home to servants of the Light who have lost faith.

Want to know more? Through the Hedgerow is out next week!

Order now. And start your own adventures through time beyond the Hedgerow...

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment