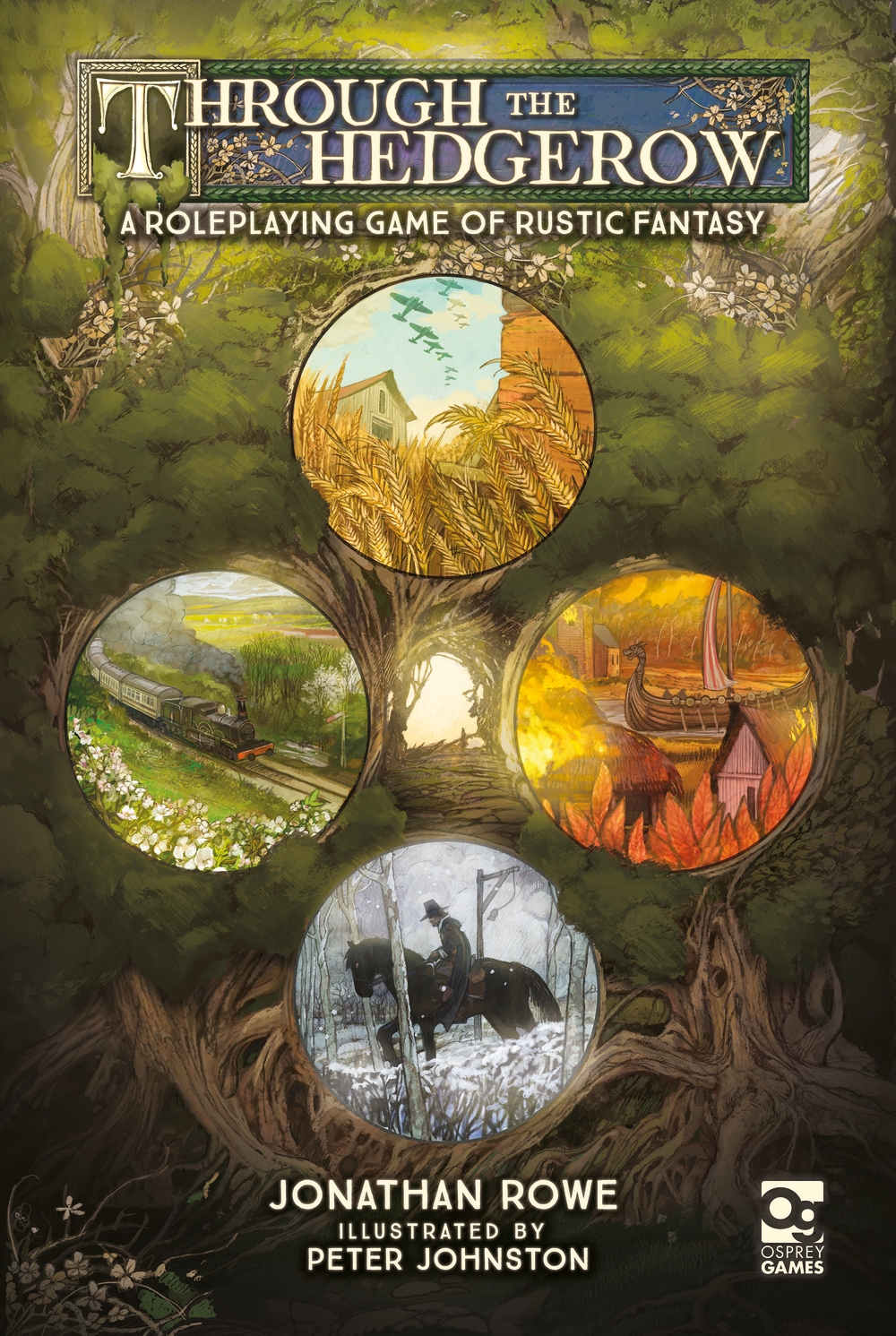

For our second blog on Through The Hedgerow, the author dives into the mechanics and what sets this rustic fantasy RPG apart from usual roleplaying experiences...

Back in 2021 I published a little indie game called The Hedgerow Hack. This had its origins in an old-school D&D session with a rural and faerie theme. In particular, it was inspired by one player character from that game, a child cleric named Bilge who worshipped a scarecrow. The Hedgerow Hack was created in the first instance to allow Bilge to have further adventures in a world that seemed more suited to him.

Karl McMichael’s original character art for Bilge.

As you might be able to tell from the name, it borrowed the rules engine from David Black’s influential The Black Hack. With this origin, The Hedgerow Hack followed the broad parameters of D&D: PCs were adventurers, equipping themselves with weapons, confronting evil by force of arms, with combat the central feature of most scenarios (albeit combat with talking squirrels and undead farm labourers, taking place in windmills, manor houses, or stone circles on hilltops, rather than in dungeons). The tone was quirky, but it was still D&D at heart.

Turning The Hedgerow Hack into Osprey’s Through the Hedgerow involved a fundamental re-think. There was the opportunity to build a brand-new rules engine and a completely different concept of what an ‘adventure’ might involve. What I wanted to do was de-centralise combat.

I discussed in a previous blog post the inspirations for Through the Hedgerow – the TV shows and fantasy literature of my ’70s childhood. What I didn’t notice as a child, though it seems so clear now, was the strong theme of pacifism running through them. Not just Doctor Who (that was actually quite a violent show by comparison); the Tomorrow People were literal pacifists, for example. In Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising, Will’s great powers as an Old One cannot defeat the Dark Rider by sheer force. In Greenwitch, Will’s fraught negotiation with Tethys is awe-inspiring, but it is the child Jane’s act of compassion that brings about a resolution. But surely the best illustration of this theme that knowledge and imagination always trump power and force – so alien to 21st-century children’s storytelling, which is rooted in the violent fantasies of the Harry Potter series – is the wizard Ged’s confrontation with the Dragon of Pendor in Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea:

He had staked this venture and his life on a guess drawn from old histories of dragon-lore learned on Roke, a guess that this Dragon of Pendor was the same that had spoiled the west of Osskil in the days of Elfarran and Morred, and had been driven from Osskil by a wizard, Elt, wise in names. The guess had held.

“We are matched, Yevaud. You have the strength: I have your name. Will you bargain?”

It only now strikes me that Marvel’s Doctor Strange (2016) had a very similar scene, when Strange confronts Dormammu, saying, “I’ve come to bargain.”

It’s hard to imagine how one could go about setting up a moment like this in most fantasy RPGs, where to be a wizard means having lightning bolts at your fingertips and a dragon (or demon) is, at the end of the day, just a problem expressed in terms of Armour Class, Hit Points, and damage output.

To be fair, there are other RPGs that have experimented with de-emphasising combat – Tales From the Loop, for example, which features PCs who are all children. Similarly, Through the Hedgerow likewise features ‘Waifs’ as playable characters – children drawn into the battle between the Light and the Dark. While I could envisage (but not enjoy) a grimdark horror-style game that places such characters in the midst of violent conflict, what I felt Through the Hedgerow needed was a rules engine that allowed even potentially deadly encounters to be resolved using abilities other than weapons and physical force. Fast-talking, bluff, trickery, emotional appeals, mystic pronouncements, running away and hiding, and courageous defiance should all have a place.

The Checks & Challenges System

Outcome Checks

In a game like Through the Hedgerow, PCs succeed at most things they attempt and dice rolls aren’t necessary. Every now and then something happens where the outcome is truly in doubt. This is the time to make an Outcome Check. The PC rolls any one of their relevant dice and the Judge rolls a Peril Die. As a player, you just have to match or exceed the Peril Die. This isn’t hard – most of the time the Peril Die is a d4, or a d6 at most. Something really horrible has to be abroad in the night to roll a Peril Die bigger than that. If you fail an Outcome Check, you don’t find what you’re looking for or get to where you were going.

It’s a pretty simple system. You, the player, choose the Die based on how you roleplay the situation. If you’re trying to talk your way out of trouble, roll Charm; if you’re hiding, roll Wits; if you fight your way out or just outrun them, roll Might, and so on. If you’ve got a useful piece of Gear, it might let you roll d8 instead, or perhaps d6 if it’s only marginally useful for the problem at hand.

Challenges

Checks are easy but sometimes the problem is bigger, more complex, or threatens very nasty consequences. This sort of problem is a Challenge and there’s a different system for that.

Every Challenge has a Threat Level (TL), from TL0 up to TL5. This indicates how many steps or episodes are needed to resolve it. Picking a lock might be TL0, just a single Threat, but being attacked by a pack of hungry wolves might be TL2, indicating three Threats in succession.

Players get to describe how their PCs deal with each Threat, taking up the narration from the Judge. You might say, “I pick up a burning branch from the fire and wave it towards the wolves!”, “I climb a tree to get away from them!”, or even, “I look deep into the wolf’s eyes and commune with its wild spirit.” If it fits the situation and your character, you can describe it.

The Threat then dishes out Peril, which is deducted from your Resolve score. This wolf pack might roll a d6 Peril, but the Judge might rule that climbing a tree is a good idea and the Peril shrinks to d4 for that character.

If you don’t want to lose Resolve (and, usually, you don’t) then you can roll dice to try to ‘soak’ the Peril. You can roll dice based on any relevant Quality, Gear, Virtue, or personality Trait. Using the burning branch might be worth a d6 (it’s not really what the firewood is for which is why you don’t get a d8 for it); climbing a tree might justify rolling your Wits Die; communing with spirits would use your Charm Die or perhaps your Gramayre Die, or both. You use the highest result and deduct it from the Peril, hopefully you won’t lose any Resolve.

This happens for the next Threat, and the next, until all the Threat Levels have been experienced. If you lose all your Resolve, you are defeated; if you’re still standing at the end, you win – the wolves retreat, you escape them, or their leader submits to your authority.

The catch is, most dice get exhausted after they are used, so for subsequent Threat Levels you have to change tactics, or else justify what you are doing in a new way. Maybe for TL0 you look into the wolf’s eyes and roll your Charm and Gramayre. For TL1 you declare, “I’m overwhelmed by the beast’s hunger and I stagger, but I find a reserve of strength in myself and maintain eye contact!” and the Judge agrees that you can roll your Might this time. For TL2, you suggest, “I offer the wolf a sandwich from my satchel,” and the Judge decides that this is worth a d6 too. Assuming you didn’t lose all your Resolve, the Challenge ends with the wolf leader devouring your sandwich and the pack leaving you in peace. This is how a PC schoolboy armed with only wits and a sandwich can overcome the challenge of a pack of hungry wolves.

Exhausted dice can be restored with various amounts of rest – a breather, a respite, or an interlude – but the risk is always that the plots of agents of the Dark will advance while you are resting!

Hazards, Humours, and Successes

Some Challenges don’t just drain your Resolve. Hazards are penalties you suffer if you lose any Resolve to the Challenge. For example, the wolf pack might have the ’Injury’ Hazard, which means that, if you lose even 1 point of Resolve, one of your own dice is ‘burned’ and is treated as a size smaller until you get healed.

The Judge might ignore some Hazards based on the way you roleplay your behaviour. Climbing the tree or waving the burning branch around definitely risks an injury, but a sympathetic Judge might rule that communing with the wolf’s spirit does not (at least not while you’re using Charm rather than Might).

Humours alter the way a Challenge works. For example, the wolf pack might have ’Armoured’ which means that any dice you use to soak their Peril that are based on force or combat are treated as a size smaller.

Once you’ve passed all the Threats, you probably enjoy a ‘Modest Success’ which means the problem is over for now but it will soon return or be replaced by another one just as bad.

You can make your Success more effective by generating ‘edges’ which you do by choosing to shrink your largest die before you roll it. Some Virtues and Gear also confer edges when used. Edges might turn a Modest success into a Minor, Major, or Outstanding Success. In the example above, the wolf pack might communicate important information to you before they leave – or even accompany you as an ally for a while.

Challenges generate ‘notches’ which counteract edges – one for each Threat Level after the first (the first Threat is ‘TL0’ as it generates no notches). There are Humours and Hazards that generate notches too. If you end up with more notches than edges, you enjoy only a Partial Success, a Bare Success, or No Success at all (which forces you to face the Challenge again!).

Putting It All Together

The Challenge System is very different from the turn-by-turn resolution systems of games like D&D. It draws some inspiration from Blades In The Dark’s system that bundles all the various possibilities of a problem into a single dice roll based on position and effect, then ticks of segments of a ‘clock’ to mark progress towards a goal.

Similarly, the Challenge System assigns a Scope value to the Challenge and to the PCs involved in it. A single person has a Scope of 1, two or three people would be Scope 2, four to six would be Scope 3, and so on. If the Challenge has more Scope, then the difference is used to increase the Threat Level or the Peril Die, or both. That TL2 Pd6 wolf pack from earlier might be Scope 2. A lone PC up against that many wolves might find the TL increased to 3 or the Peril Die increased to d8, whichever makes things more dramatic. You can ignore Scope when size and numbers don’t amount to an advantage – climbing the tree, for example. In the same way, if the PCs have more Scope, they can reduce the TL or Peril Die. Four PCs confronting the wolf pack could reduce it to TL1 or Pd4.

I’ve loaded the Challenge System with enough nuances to entertain all kinds of players. Martial characters – clawed Buggebers, tragic Hodkin, warrior-wizard Ouzels, and the like – can shine in battle, but combat can also involve speeches, emotional appeals, curses, and dramatic flourishes (in true The Princess Bride style) rather than just relentless pummelling. Meanwhile, players who want to cast ritual spells, perform Glees (magical songs), or win riddle contests are still in the thick of things.

And Then There’s Defeat

Even if you de-centralise violence, PCs will still sometimes lose and there need to be consequences for that. Not every Challenge involves the threat of injury or death, but something needs to happen.

My solution was to create a selection of Defeat Caps ranging from ‘Distraction’ (you’re a bit weak until you get to rest), through ‘Stricken’ (where you burn your Dice until you get proper healing) and ‘Captured’ (where you’re out of the story for a while) and ultimately ‘Vanquished’ (where you’re out of the story for the rest of the adventure).

In the example with the wolf pack, the character swinging the burning branch risks being Vanquished or Stricken (as the wolves tear into him), the PC in the tree risks being Captured (if she can’t get back down), and the character mystically communing with wolf spirits might be Distracted or Weakened.

But even that isn’t guaranteed. Players get to argue for a lesser Defeat Cap they find preferable and make a sort of saving throw called a Defeat Check. If the PC passes the Check, things work out as they describe it.

Waif PCs, meanwhile, can substitute being Captured for any other serious Defeat Cap. Remember in The Lord of the Rings, where Boromir was vanquished but the innocent Merry and Pippin were captured by the Orcs, only to escape later?

This approach gives players a huge amount of agency. You get to describe the drama of the Challenges you face and select dice that match your description. Even if you are defeated, the consequences of your defeat match the sort of drama you envisaged, and if you don’t like that you still get a chance to substitute those consequences for preferable ones.

Does this make Through the Hedgerow a ‘fluffy’ sort of RPG where nothing truly bad ever happens to anyone? No, characters can be Vanquished easily enough. A lot depends on the tone the Judge and players want to establish – gritty and dangerous, romantic and whimsical, or somewhere in between.

The point of these unusual rules that depart from the conventions of fantasy RPGs is that players are liberated from caution and concern over safety. You can confront the evil Witch-Hunters with a thundering denunciation, you can appeal to the honour of a crazed berserker, you can commune with the spirit of a ravenous wolf. Or at least, you can try and you don’t need to be held back by the worry about what might happen if you fail.

I was delighted when the talented Peter Johnston incorporated Bilge into the artwork for Through the Hedgerow. There he is, spying on the Cailleach as they brew their potions and lay their plots. Can you spot him?

Next week, we'll be back with our last author blog, all about the battle between Light and Dark at the heart of the game...

Through the Hedgerow is out September 26 in the UK and September 24 in the US.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment