Yugoslavia 1941–44: Anti-Partisan Operations

By Pier Paolo Battistelli

Illustrated by Johnny Shumate

PARTISANS FIGHTING THE ‘DEVIL’ DIVISION, SUMMER 1943

In an attempt to bolster the Croatian capabilities to fight the Partisans, the Germans decided to create legionnaire divisions with Croatian rank and files and German cadres, following the good performance of the 369. (Kroat.) Infanterie Regiment, which was employed on the Eastern Front and was eventually destroyed at Stalingrad. The first of the Croatian divisions formed by the Germans was the 369. (Kroat.) Infanterie Division, raised on 21 August 1942 in Germany with Croatian conscripts. The unit, eventually nicknamed the Vražja ‘Devil’ Division (following the tradition of a division that had fought with the Austro‑Hungarian Army in World War I), was deployed to Yugoslavia in January 1943. After the conclusion of the series of anti‑partisan offensives, particularly Operation Schwarz, the 369. Division pursued the withdrawing Partisans in the Tuzla area before being re‑deployed in the area of Sarajevo, mostly with the task of securing the railroads. After a period of calm, the Partisans became active at the end of August and beginning of September 1943, following the Italian surrender. Clashes between the Croatian legionnaires and the Partisans became more frequent, the former being distinguished by their chequered shield worn on the German uniforms (veterans of the 369. Regiment wore a specific badge). At this point, Tito’s Partisans were being supplied by the Allies on a large scale, with the consequence that many of them started wearing British battledress along with the customary captured Italian and German uniforms. That not only produced a more homogenous appearance, but the Partisans’ armament was also improved due to the widespread use of British weapons, most notably the Bren light machine guns, Lee–Enfield rifles and sub‑machine guns like the British Sten and American M1 Thompson. On the other hand, the Croatian legionnaires mostly relied on the customary German weapons like the standard Karabiner 98 and the ubiquitous MG 34 light machine gun.

Artwork requested by Paul Williams

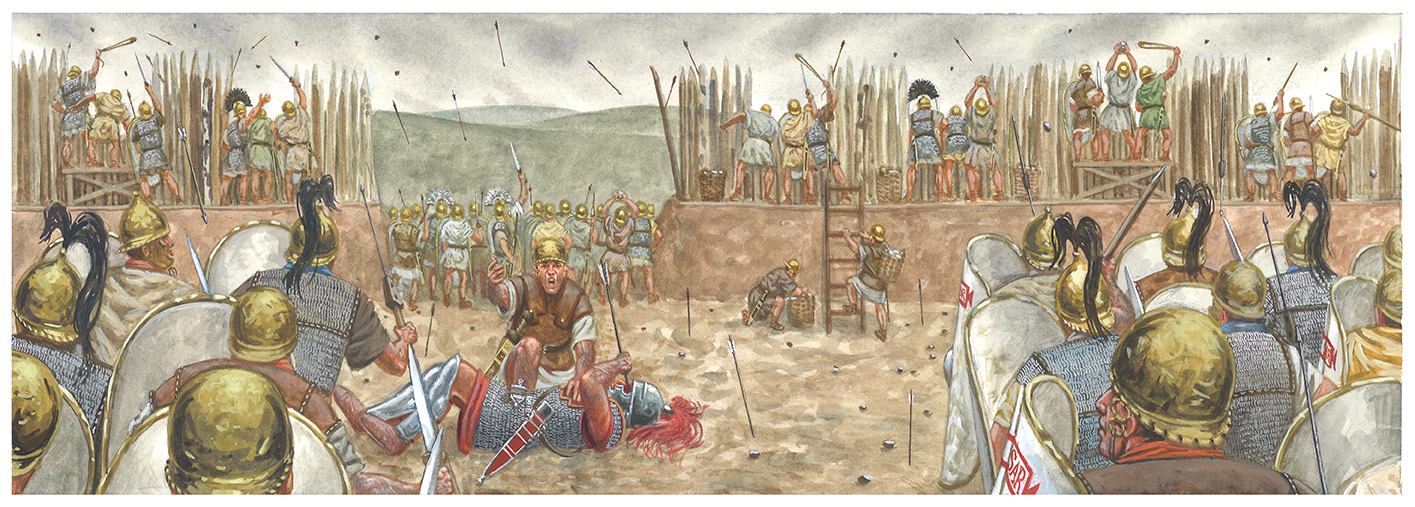

Caesarian Legionary vs Pompeian Legionary: Rome’s Civil War 49–45 BC

By William Horsted

Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava

Caesarian view: The gateway must be held. As he sprints across the fort, a Caesarian legionary ignores the screams of a centurion hit in the eye by an arrow, and the pleas of a soldier trying to help him. Stones smash into helmets and clatter off armour; swishing arrows pierce raised shields or cut deep into unprotected flesh. The Pompeians are approaching for another assault, and the legionary has been ordered to leave his post on the rampart to aid Scaeva and the few men of his century still standing in the opening. Scaeva has led the defence at the gate all day, and as the legionary runs to help, he is thrilled to hear the valiant centurion’s furious battle cry soaring over the clamour.

On the rampart, officers exhort the rest of the men to hold their positions. Soldiers scrabble to find stones and carry them in baskets up to the defences above: these small rocks dug from the ground within the fort are the only missiles available to the Caesarian slingers. Other soldiers get ready to drop larger rocks directly onto the attackers as they approach the base of the wall. As the legionary passes the wounded centurion, writhing and shrieking in a growing puddle of his own blood, he wonders: how much longer can our cohort hold on?

Artwork requested by Daniel Figueroa Giraldez

US Navy Atlanta-class Light Cruisers 1940–49

By Mark Lardas

Illustrated by Stefan Draminski

RENO FINISHES PRINCETON

During the battle of Leyte, at 0938hrs on October 24, 1944, a D4Y dive bomber evaded interception and hit the Princeton with a 250kg bomb. It penetrated deep into the ship, igniting a massive fire in the hangar deck. The fires could not be brought under control, despite assistance from cruisers Birmingham and Reno and three destroyers.

As the day advanced, the fires got worse. Ships assisting Princeton, including Birmingham and the destroyer Irwin, had been damaged by explosions aboard Princeton as they fought fires. Reno was damaged when Princeton lurched over suddenly as Reno was alongside. Power to the pumps was out and the magazines could not be flooded. It was too dangerous to tow Princeton, several earlier attempts having failed. Finally, the order was given to scuttle the carrier. At 1600hrs, Captain Buracker, commanding Princeton, ordered it abandoned. Shortly after Buracker became the last man to leave Princeton, Admiral Frederick Sherman, commanding the task group, ordered Princeton torpedoed. Initially, Irwin got the job, but Princeton had damaged the destroyer’s torpedo director badly enough that Irwin’s torpedoes proved more dangerous to itself than Princeton. Sherman instead gave the assignment to Reno.

Shortly after 1700hrs, Reno fired two torpedoes at the stationary Princeton, less than a mile away. Both ran straight and true, striking Princeton as aimed, under the forward gasoline tank. The 100,000 gallons of aviation gasoline exploded, destroying Princeton in a massive fireball. This illustration depicts the results of the torpedo hits.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment